Supermarine Spitfire dead ends

The British had acquired the manufacturing rights of the 20-mm Hispano-Suiza HS.404 cannon with explosive shells, but its installation on the wings of fighters was problematic. The weapon had been designed as an integral part of the Hispano-Suiza HS.12 Y-31 engine and lacked structural strength to act independently. The adaptation was difficult; during the Battle of Britain, some

Spitfires Mk I of the 19th Sqn were experimentally equipped with two Hispano Mk I, suffering numerous stoppage problems. The RAF avoided its usage until the appearing of the Mk II in the summer of 1941.

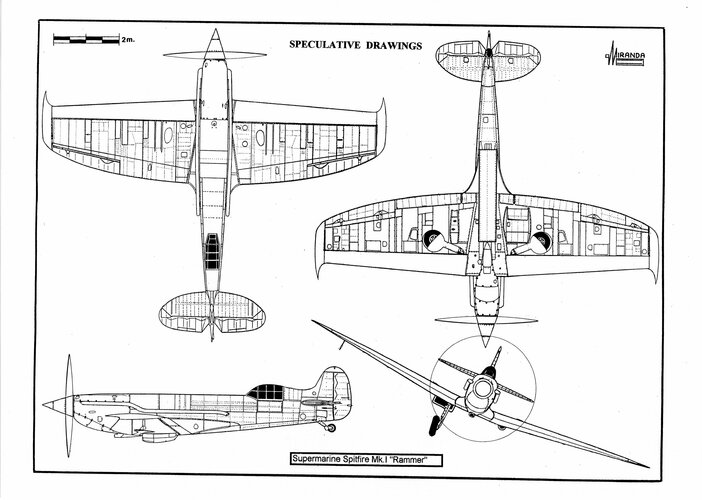

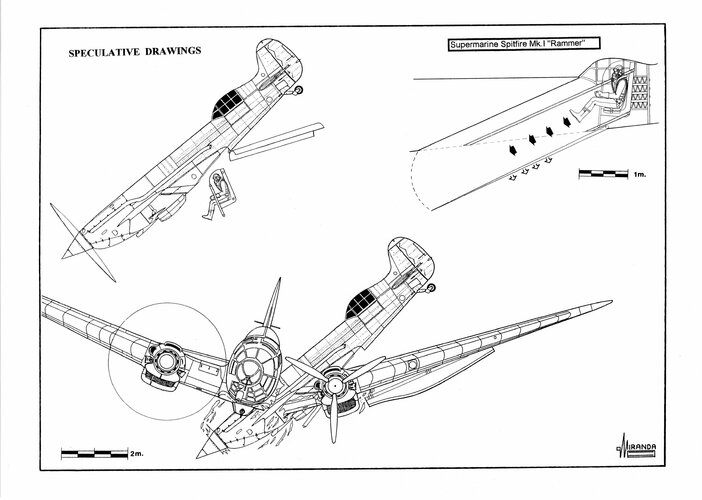

Several methods were considered to mitigate this situation, including air-to-air bombing and rockets vertically fired from the rear fuselage of the Hurricanes. Another idea was the ramming, inspired in the Soviet

Taran tactics, developed in Spain and Khalkhin Gol that assured the destruction of an enemy bomber by collision. In the summer of 1940, the British pilots were forced to resort to ramming in some extreme combats, destroying four Bf 109, two Do 17, one Ju 88, one Bf 110, one Fiat CR.42 and one He 111.

The ramming sometimes happened accidentally due to miscalculation of distances by the attacking aircraft or because the pilot had been injured or killed by the defensive fire of the attacked aircraft. At other times, it was a desperate measure, consequence of the malfunction of arms in a conventional attack made from behind. The impact used to occur at low speed—between 40 and 80 kph—because both aircraft were flying in the same direction, with the propeller of the attacking plane acting as a circular saw on the tail surfaces of the attacked plane. The rammer usually suffered damages in the propeller, engine bearings, and engine cowling; the survival rate of the pilot used to exceed 50 per cent with a good chance of making a glide landing.

When ramming large aircraft, it was more effective to target the fuselage section between wing and tailplane to sever control cables, but the side attack manoeuvre required a very precise calculation of relative speeds that only very expert pilots could perform. The impact, between 300 and 450 kph, used to boot a wing of the attacking aircraft that fell into an uncontrollable flat spin; the pilot was violently thrown in the opposite direction to the damaged wing, getting wounded or shocked and with survival possibilities below 25 per cent because the fuselage airframe tended to deform, rendering the opening of the cockpit very difficult.

The most effective ramming, and also the most extreme solution, was the head-on-attack, a manoeuvre that Japanese pilots termed

Tai-atari (body crashing) in which both aircraft crashed at a joint speed close to 1,000 kph with decelerations of up to 100

g. No one could survive an impact like this, with the rammer embedded into the nose of the bomber and both aircraft falling intertwined. Any aircraft could be used for this task if it had enough ceiling and speed to reach the target. The main problem was the survival of the pilot after a collision in a time when ejector seats did not exist.

In May 1939, the British inventor Mr. I. Shamah proposed to the firm Phillips and Powis (later known as Miles) the transformation of a standard fighter into a specialised rammer. The modification included the replacement of the engine by a surplus Rolls-Royce

Kestrel and the guns by an armoured wing-leading edge, the installation of steel rammers in the propeller hub and wingtip, and one downwards ejector seat located over a ventral hatchway.

The idea was considered in 1940, due to the shortage of experienced pilots that mastered the technique of the deflection shooting. Out of the 2,330 fighter pilots who fought against the

Luftwaffe between July and November, only 900 managed the destruction of an enemy aircraft, almost always by surprise and firing from closer than 200 m.

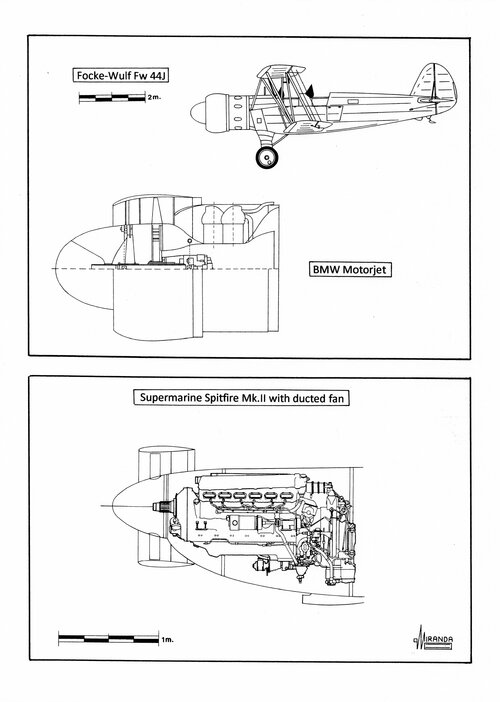

In 1929 Frank Whittle investigated the possibilities of the ducted fan driven by a piston engine. In the late 1930s, Max A. Mueller, engineer of the firm Junkers AG, patented a ducted-fan device that greatly improved the performance of the conventional propellers. In 1938, a team of technicians of the company BMW GmbH, under the leadership of Dr.-Ing. Hermann Oestrich, modified a Bramo 325 radial engine fitted with a four-bladed ducted-fan with a diameter of 1 m. The modified engine, named

Motorjet, was installed in a trainer Focke-Wulf Fw 44 and successfully tested in flight by Hanna Reitsch.

The ducted fans provided more static thrust for the same amount of power than a conventional propeller of same diameter and could operate at higher rotational speeds. In 1940 it was proposed the installation of a four foot diameter cowled propeller assembly in one Spitfire Mk.II, but the idea was not taken further as the device would have considerably diminished the pilot’s forward view.

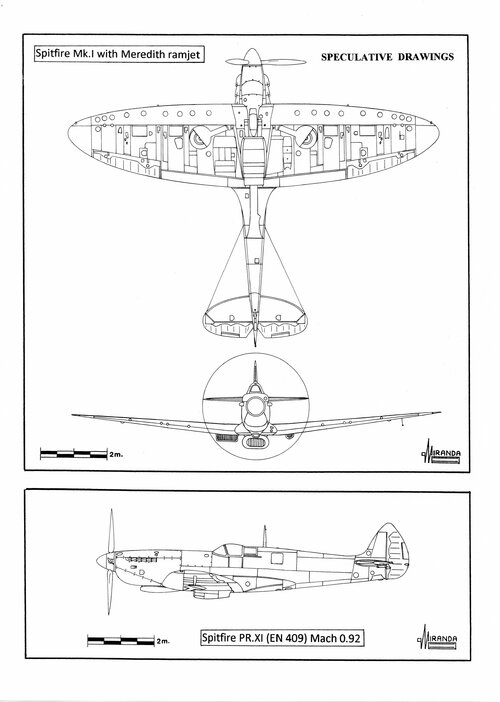

In May 1940 engineers at the R.A.E. began experimenting with a

Meredith ramjet housed in a 48x30x15 inch duct mounted under the belly of a

Spitfire Mk.I, as a third radiator, but the experiment was abandoned during the Battle of Britain. In June 1944 the ramjet idea was reconsidered, to boost the

Spitfire Mk.IX during the

Operation Diver against the V-1 flying bombs, but the German missiles had been beaten before the bench tests were solved.

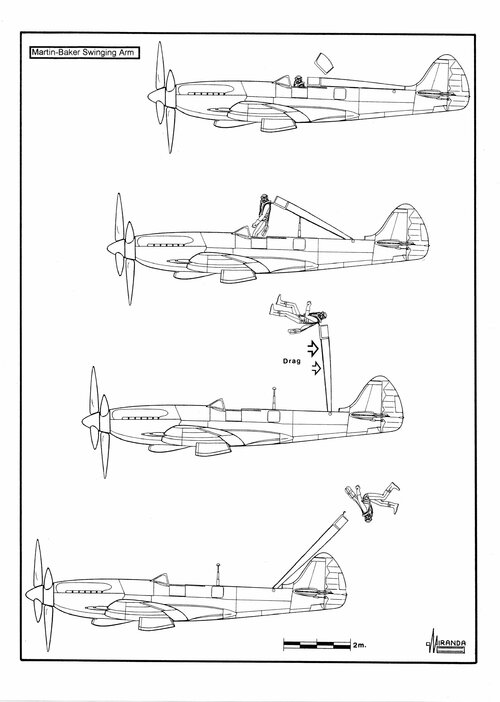

By 1943, the increasing speed reached by the fighters created many difficulties for bailing out as the air pressure acting over the pilot tended to return him to the cockpit or impact against the tail surfaces. In the

Spitfire Mk 21, the plan was to install the 'swinging arm', a Martin-Baker invention, to help the pilots overcome the air pressure at high speeds. The upper part of the fuselage detached itself to form an articulated arm that extracted the pilot from the cockpit by means of two hooks inserted in the parachute harness. The arm was actioned by powerful springs and by the air drag, rotating around a hinge located at the base of the tailfin, launching the pilot backwards over the tail surfaces.

The project was started in 1944. A model of this scheme was shown to Sir Stafford Cripps, Minister of Aircraft Production and Air Chief Marshall Sir Wilfred Freeman, at the Ministry on 11 October, 1944 although it was finally decided to use the seat fitted with an explosive catapult as it was lighter and required fewer modifications in the airframe.

In November 1939, Supermarine started the design of the Type 338, a navalised version of the

Spitfire Mk.IA powered by one Rolls-Royce

Merlin III engine. The project was submitted to the Fleet Air Arm on 2 January 1940 and a contract for 50 airplanes was signed in February but was cancelled on 16 March to not interfere with the production of the

Merlin engine. Supermarine considered the possibility to use the

Rolls-Royce

Griffon designed in 1938 after a request of the Royal Navy. A prototype already existed in November 1939.

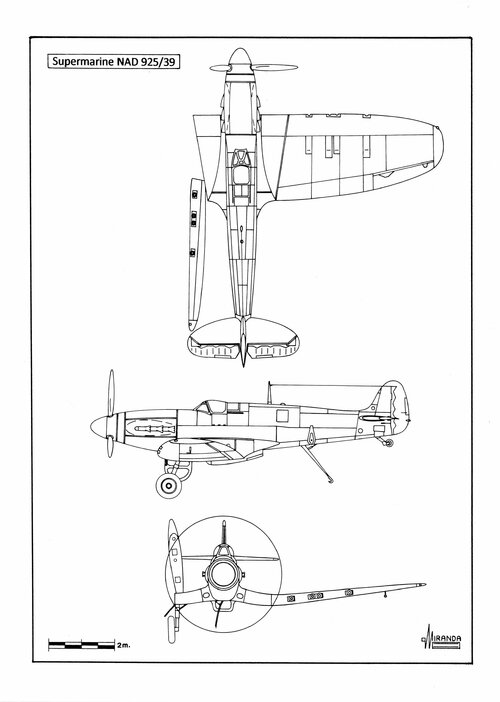

On 16 December 1939, Supermarine issued the Technical Office Report NAD 925/39, a navalised version of the

Spitfire Mk.IA powered by one 1,730 hp

Griffon IIB, 12 cylinder Vee, liquid-cooled engine, with one-stage, two-speed supercharger. The new engine weighted 1,790 lbs and had a length of 5.9 ft. Its installation in the airframe of a

Spitfire Mk.IA required to increase the fuselage length by 20 cm to compensate the higher weight and power of the

Griffon. The NAD 925/39 was 2,316 lbs heavier than a standard

Spitfire, had fold-back wings could take off in 300 ft against a 20 knots wind.

NAD 925/39 technical data

Wingspan: 36.8 ft (11.22 m), length: 30.6 ft (9.32 m), height: 10 ft (3.04 m), wing area: 242 sq. ft (21.78 sq. m), maximum weight: 8,100 lbs (3,670 kg), estimated maximum speed: 396 mph (637 kph) at 15,000 ft, armament: eight wing-mounted 0.303-in Browning machine guns.

The Admiralty was not interested in another

Spitfire Mk.IA converted. The Fleet Air Arm needed a new fighter designed specifically for naval operation and the NAD 925/39 was rejected. On 15 February 1940 Supermarine issued the Technical Report Nº 2846, a navalised version of the

Spitfire F Mk IV, with inverted gull folding wings, split flaps with increased area, inward retracting landing gear, arrester hook and catapult gear.

The airplane was powered by one 1,735 hp

Griffon RG2SM engine, with one-stage, two-speed supercharger and armed with six wing-mounted 13.2 mm FN-Browning heavy machine guns. Early 1940, on the orders of the Minister of Aircraft Production, work on the

Griffon engine had been halted temporarily to concentrate on the urgently needed

Merlin III. The Nº 2846 proposal was rejected on 29 March 1940.

Report Nº 2846 technical data

Wingspan: 40.4 ft (12.31 m), folded wingspan: 10.3 ft (3.15 m), length: 31.9 ft (9.72 m), height: 10.8 ft (3.3 m), wing area: 249 sq. ft (22.41 sq. m), maximum weight: 10,350 lbs (4,689 kg), estimated maximum speed: 397 mph (639 kph), armament: six wing-mounted 13.2 mm FN-Browning heavy machine guns.

In the Autumn of 1941, when the Luftwaffe offensive stabilised and the war at sea reached a highly critical phase, the Admiralty obtained permission to acquire 166

Seafire IB (Type 340). The naval fighter was almost identical to the

Spitfire Mk.VB, apart from the A-frame arrester hook and the slinging points.

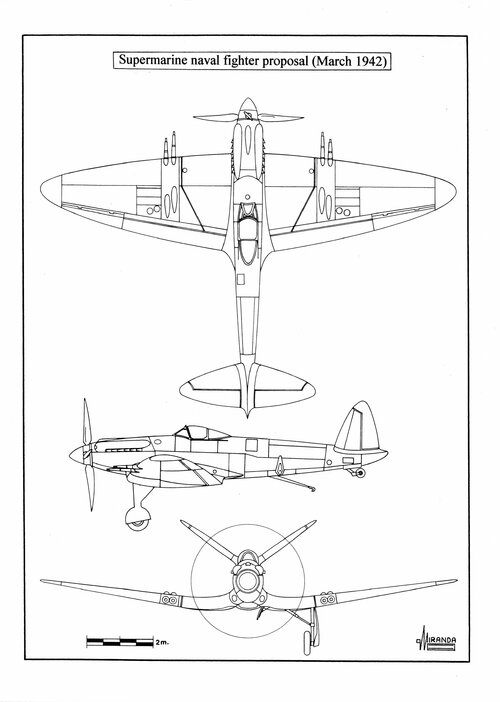

The

Griffon engine was available in March 1942 and Supermarine proposed a naval version of the

Spitfire F Mk IV (Type 337) powered by one 1,735 hp Rolls-Royce

Griffon III with one-stage, two-speed supercharger driving a four-blade airscrew with 10 ft 9 in of diameter. The new fighter was fitted with inverted gull wings, inward retracting landing gear, modified ventral radiator, ‘butterfly’ tailplane and four wing-mounted 20 mm Hispano cannons. The project was dropped in favour of the manually-folding wings

Seafire III (Type 358), a total of 1,220 machines being built with Rolls-Royce

Merlin 55 engines.

Supermarine naval fighter proposal (March 1942) technical data

Wingspan: 41 ft (12.5 m), length: 31.6 ft (9.63 m), height: 12.9 ft (3.95 m), wing area: 275 sq. ft (24.75 sq. m), armament: four wing-mounted 20 mm Hispano cannons.

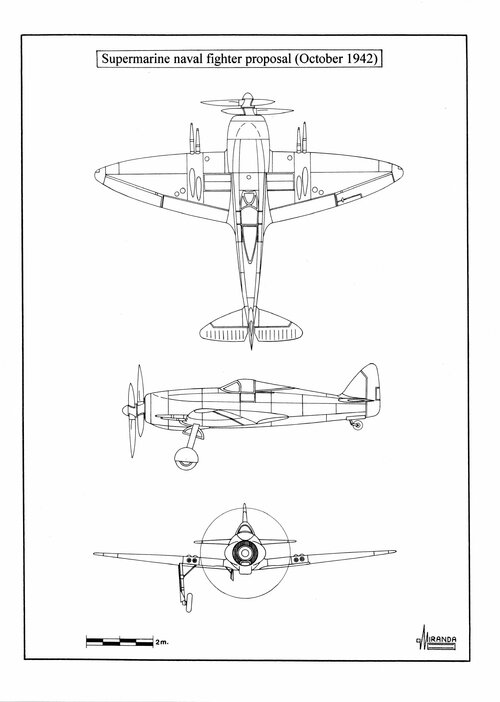

On October 1942 the Admiralty received a new Supermarine proposal for a point-defence interceptor fighter powered by one 2,240 hp Napier

Sabre IV, twenty-four-cylinder, horizontal H, liquid-cooled engine driving a three-blade contra-rotating airscrew.

Supermarine naval fighter proposal (October 1942) technical data

Wingspan: 30.4 ft (9.27 m), length: 25.3 ft (7.7 m), height: 11.2 ft (3.4 m), wing area: 200 sq. ft (18 sq. m.), armament: four wing-mounted 20 mm Hispano cannons.

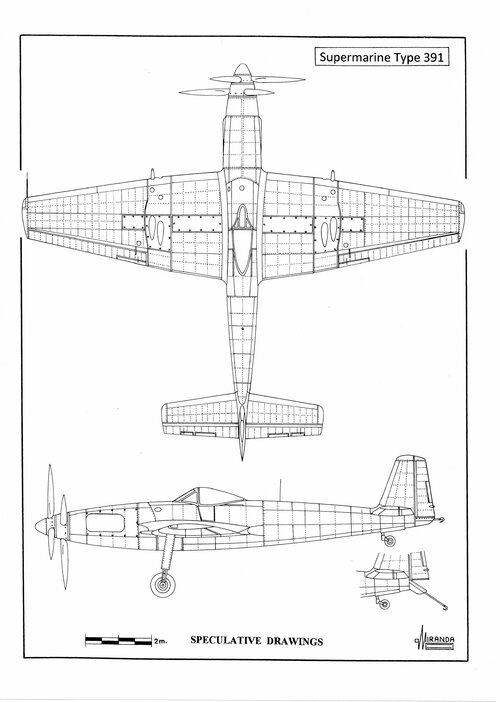

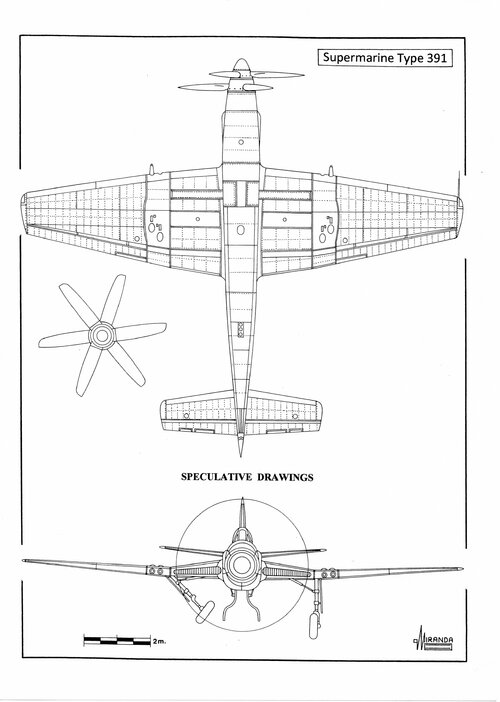

On March 1944 Supermarine initiated the design of the Type 391 (a 120 per cent homothetic enlarged version of the N5/45

Seafang), powered by one 3,500 hp Rolls-Royce

Eagle II, twenty-four cylinder, horizontal H, liquid-cooled engine driving a six-bladed contra-rotating airscrew. On 20 June 1944, the project was submitted to the Royal Navy but was eventually dropped in favour of the Type 392 jet-powered fighter.

Type 391 technical data

Wingspan: 46.3 ft (13.3 m), length: 39.7 ft (12.10 m), height: 14.8 ft (4.54 m), wing area: 335 sq. ft (31.2 sq. m), maximum weight: 15,750 lbs (7,144 kg), estimated maximum speed: 546 mph (879 kph), range: 880 mls (1,415 km), armament: four wing-mounted 20 mm Hispano cannons.

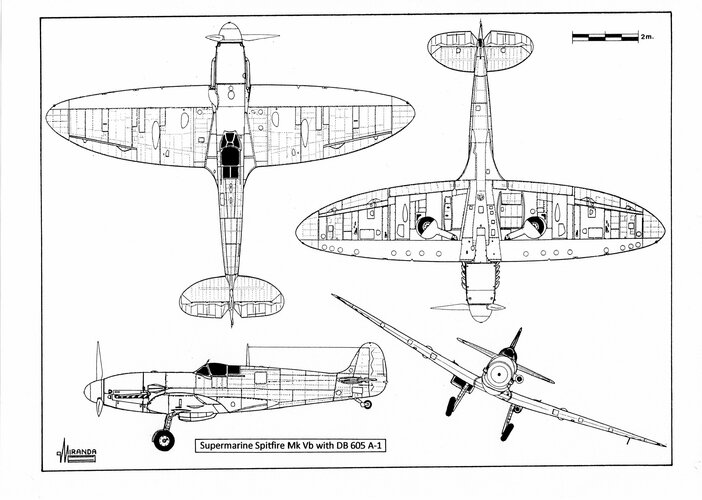

On 18 November 1942, the

Spitfire VB (EN830) from Nº 131 Sqn was captured intact in the German occupied Isle of Jersey. The aircraft, coded NX-X, was dismantled and shipped to the Daimler-Benz test facility at Echterdingen. On December 1943 it was extensively modified with the installation of one DB 605 A-1 engine, with the cowling and carburettor scoop from a Messerschmitt Bf 110 G and the variable pitch VDM 9-12159A propeller from a Messerschmitt Bf 109 G.

The 12-volt electric system was replaced by one 24-volt Fl 32629-1 system, German instruments and Pitot tube was also installed. The cooling system, except the British radiator, was replaced by one coming from a Bf 109 G, the hydraulic system was modified, and the fuel pump was replaced. The fuel tank was replenished with 170 lt. of 87-octane B4 gasoline and the oil tank with 40 lt of

schmierstoff lubricant. The aircraft was coded CJ+ZY and painted RLM 74/75 on the upper surfaces, RLM 65 lower surfaces and RLM 04 elevators, rudder and engine cowling.

Flight tests performed in the

Abteilung E2 of

Erprobungsstelle-Rechlin, revealed that the German engine gave better performance than the Merlin 45, with an impressive climb rate of 69 ft/sec and 41,656 ft ceiling, 5,166 ft more than that of a

Spitfire Mk.VB. The aircraft was still equipped with a British radiator and could not exceed

490 mph top speed to avoid overheating of the engine. The CJ+ZY was heavily damaged on 14 August 1944 when a formation of B-17 bombers attacked Echterdingen.

CJ+ZY technical data

Wingspan: 36.8 ft (11.23 m), length: 30 ft (9.14 m), height: 13 ft (3.96 m), wing area: 242 sq. ft (21.78 sq. m), maximum weight: 6,026 lbs (2,730 kg), maximum speed: 490 mph (788 kph), climb rate: 69 ft/sec (21 m/sec), service ceiling: 41,656 ft (12,700 m), armament: none.

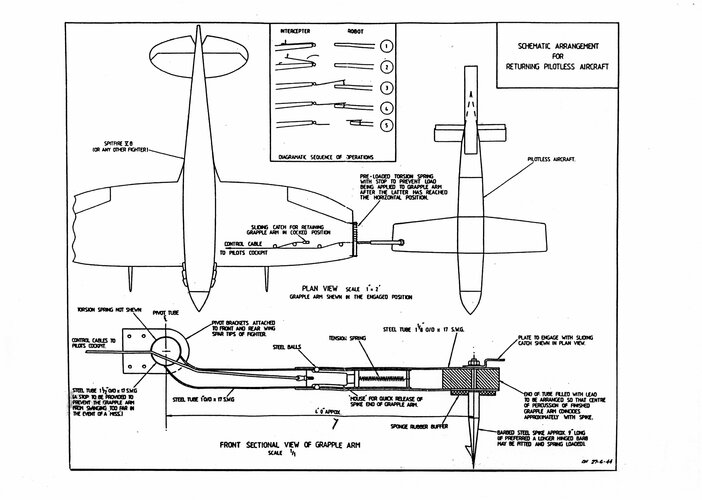

During the demolition of the Desford Airfield hangars, it was discovered one schematic arrangement for returning pilotless aircraft. The 11 June 1944 print shows a plan for fitting

Spitfires LF Mk XIVe with a device for capturing V-1 flying bombs, turning them round and releasing them in the opposite direction. There is no record of it ever having been attempted.

On D-Day, the

Luftwaffe had lost the air superiority over their own airspace. All the Reich air bases were within reach of the Mustangs and were regularly bombed to keep the runways unusable. Very few of the 39,807 German aircraft manufactured in 1944 had the opportunity to fight. Paralyzed on land for lack of fuel, they were destroyed by air strikes. In 1945 the few survivors were forced to operate from the

Autobahnen.

The piston engine fighters were most affected by the lack of fuel. After the

Bodenplatte Operation, only 1,300 airplanes continued fighting. They were airplanes propelled by turbojets of the types Arado Ar 234, Messerschmitt Me 262 and Heinkel He 162 and a hundred Messerschmitt Me 163 rocket fighters that used

sonderkraftstoff (experimental propellants). As German fuel reserves declined, the OKL cancelled a large number of aircraft projects; first the heavy bombers, then the piston fighters and finally the turbojet powered aircraft that required long runways. Also eliminated were the rocket fighters with landing skids, when the experience gained with the Me 163 proved that their low mobility on the ground made them extremely vulnerable to strafing attacks by enemy fighters.

Finally, the VTOL was the only option left.

By early 1944 Professor Walter Georgii and Oberst Siegfried Knemeyer, director of the Research and Development Institute of the Luftwaffe, initiated contacts with several aeronautical companies looking for ideas for the construction of a

senkrechtstarter jagdflugzeug (tailsitter VTOL fighter) that could operate independently of the runways.

In the late 1930s, Dipl. Ing. Otto Muck, of Siemens, patented a project of tailsitter aircraft with contraprop airscrews. In 1940 a team of engineers from AVA-Göttingen calculated that a VTOL aircraft of 5 tons would require 4,000 hp power to lift-off, an engine that did not exist at the time. On January 1944, Daimler-Benz built a twenty-four cylinders engine with 3,800 hp, called DB 613, formed by two DB 603 G engines coupled together to drive a single-shaft power with counter-rotating airscrews. But the set weighed two tons and was not useful to propel a VTOL aircraft. At the end of 1944 Dr. Ing. Gerhard Schulz and designer Karl Reiniger of Heinkel-Vienna designed a tail sitter point-defence interceptor fighter with annular wing, called

Lerche, based on the aerodynamic theories of Dipl.-Ing. Von Zborowski. It was propelled by two DB 605 DC piston engines, with 2,000 hp each, installed nose-to-nose so propellers would rotate in opposite directions without using heavy and complex reduction gears. Its estimated lift-off weight was 5,600 kg.

In May 1944 Daimler-Benz received an order from RLM to concentrate on the development of a turboprop version of the Heinkel 109-011 turbojet, dubbed DB 109-021, with 2,400 hp of shaft power, 585 kp of residual jet thrust and 1,266 kg. It was selected by Heinkel to power a tailsitter fighter project, with the Zborowski annular wing, called

Wespe, and an estimated lift-off weight of only 2,140 kg. The turboprop operated two counter-rotating, variable pitch, three-bladed airscrews through reduction gearing with 1,800 rpm constant speed. The annular wing increased the propeller efficiency and generated lift during the horizontal flight.

Lerche and

Wespe were proposed to OKL on 2 February 1945.

On ground the Heinkel tailsitters were kept upright over four tailfins and the narrow landing gear track affected the stability during vertical landing. In August 1944, the firm Focke-Wulf developed a semi-automatic landing system para el VTOL

Triebflügeljäger. Data on the semi-automatic landing procedure plan have not been kept. It might be expected that it might have used part of the ‘blind bomb’ and ‘level bomb’ electronic equipment developed for the Arado Ar 234 and adopted by the firm Focke-Wulf for its project

1000 x 1000 x 1000 bomber. After making the transition to the vertical flight on the landing area, the pilot would connect the three-axis Patin PKS autopilot and the Lofte tachometric bomb-sight rear periscope. Both devices acted together with the FuG 101a radio-altimeter, driving the airplane according to the pilot movements over the bombsight.

On 8 January 1941, an engineer of the Bell Aircraft Corporation named Arthur Young applied for a patent of a project of a tailsitter type VTOL. It was propelled by a radial engine located behind the pilot that, by means of a geared drive shaft, actioned two big contra-rotating propellers. It was a clever application of the technology developed by Bell in 1937 to propel the P-39 fighter. For security reasons, the patent (No. 2382460) was not published until 14 August 1945.

In 1946, the Juriev OKB Soviet bureau of design developed a point defence VTOL fighter based on the propulsion system of the

Airacobra under the name Jurijev KIT-1. The novelty, compared to the Young design, consisted of the usage of propellers with different diameter measures. The forward metallic two-bladed was used for propulsion purposes only. The rear one, with a light structure partially covered by fabric, like the autogyro’s rotors, was used to balance the rotation of the other during take-off and landing and both had the same weight. There is no information about the rotor being articulate to improve the control of the machine in vertical flight or if this was achieved by the control surfaces located in wings and tail. In horizontal flight, the rotor of big diameter was disconnected from the drive shaft, blocking it in parallel to the wing with 0 degrees pitch, acting as a

canard plane.

Between December 1941 and April 1942, the Japanese offensive cost the British the loss of the Singapore naval base, one battleship, one battlecruiser, one aircraft carrier, three cruisers, four destroyers and more than 300 airplanes. Early 1944 the Japanese kept a hard fight that it was foreseen would be long and costly. The Royal Navy considered the possibility to lose all their aircraft carriers under

kamikaze suicide attacks; in that case it would have been necessary to develop an high-performance, catapult-launched floatplane fighter specifically designed by the air defence of the Fleet. The Blackburn B.44 was designed for operation from small seaplane carriers out of range of shore bases and from island sites with minimal infrastructure.

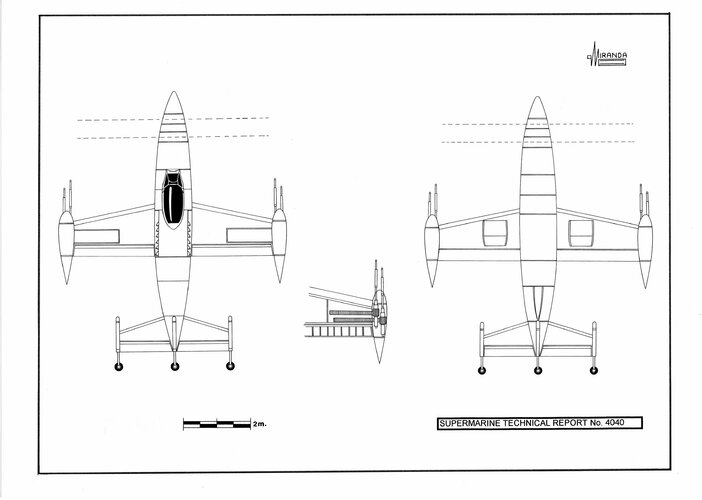

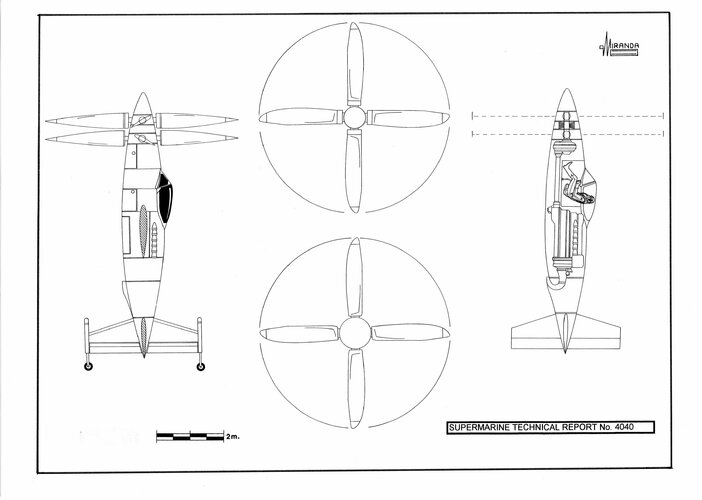

But there was another possibility. On 26 February 1944, Supermarine published the Technical Office Report No. 4040 with the description of a VTOL tailsitter fighter designed by A.N. Clifton.

It was a single-seat high performance fighter designed to protect the Fleet or convoy vessels from attack by enemy aircraft operating from small platform areas afloat or ashore.

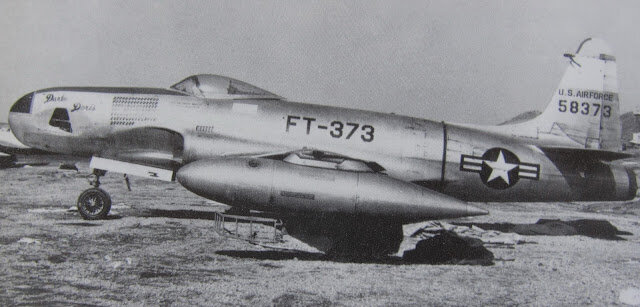

The propulsion system had already been developed by Rolls-Royce for the

Mustang F.T.B. It was a 2,490 hp

Griffon 58 located behind the pilot connected to the reductor gearbox of the 5.9 m of diameter 8-bladed contra-rotating propellers by means of a long power shaft.

Not requiring a big wing surface to take-off or landing, the wings could be very small and light and the fuselage was reduced to a cone located behind the engine, to serve as support for the four tail surfaces.

Being available the first turboprop engines during the first 50s, new designs of tail-sitters appeared based in the same formula. The Lockheed XFV-1, the Convair XFY-1, the Northrop N-63 and the Martin Model 262 were not successful as a practical vertical flight control system could not be found.

Supermarine Technical Report No. 4040 (Technical data)

Power plant: one 2,490 hp Rolls-Royce

Griffon 58, twelve-cylinder Vee, liquid-cooled engine, with one-stage, two-speed supercharger and water/methanol injection power boost, wing span: 22.4 ft (6.84 m), length: 27.6 ft (8.42 m), wing area: 100 sq. ft (9 sq. m), maximum take-off weight: 15,000lbs (6,795 kg), maximum speed: 450 mph (724 kph), armament: four wing pods-mounted 20 mm Hispano cannons

In late 1943 the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) had begun a systematic high-speed research programme using

Mustangs and

Spitfires diving to above Mach 0.80, the most dangerous flight tests in the history of aviation. A typical dive would start at 40,000 ft, finally reaching 89 per cent of the speed of sound (606 mph) at about 29,000 ft. The January 1944 RAE Report Aero 1906 stated the

Spitfire superior performance above Mach 0.75, by comparison to the

Mustang, due to its thinner wing.

On 27 April 1944, the

Spitfire P.R.XI EN409, flown by Squadron Leader Anthony F. Martindale, eventually reached Mach 0.92 (620 mph). The aircraft was damaged losing the propeller and the reduction gear, Martindale was knocked unconscious when the change in the centre of gravity forced the airplane to pitching up violently, at high-g, and climbing at 40,000 ft out of control. The pilot managed to glide the aircraft back to Farnborough to make an emergency dead-stick landing.