The

Phoney War ended with the invasion of Belgium and the Netherlands and the German attack against France, using 860 fighters Bf 109E, three-hundred-and-fifty Bf 110, 1,120 medium bombers, 342 dive bombers and 591 reconnaissance airplanes.

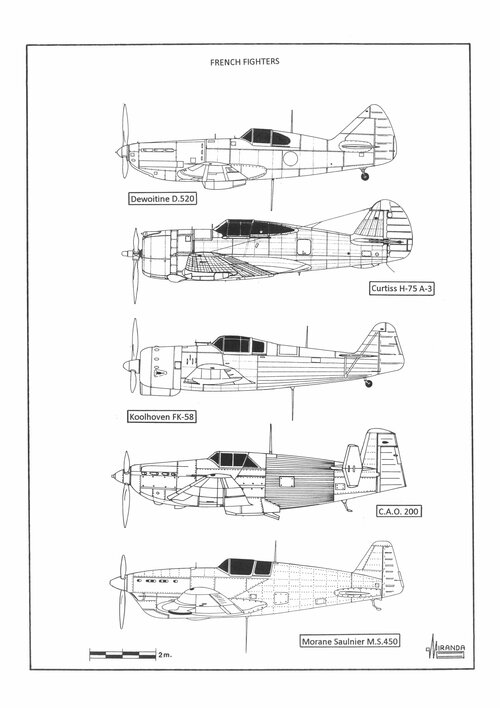

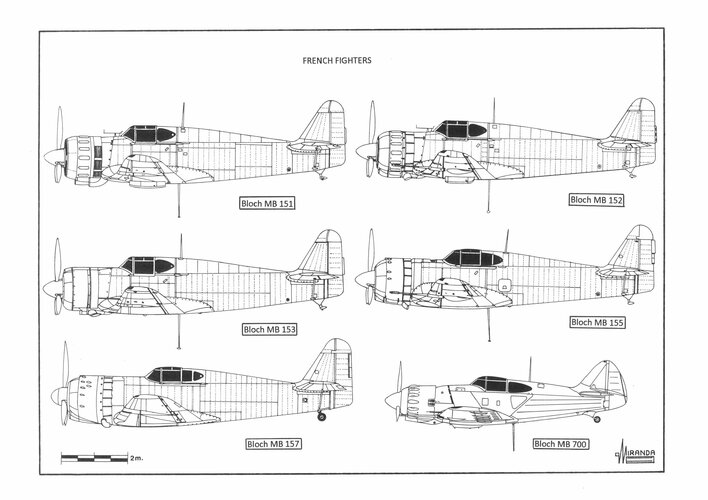

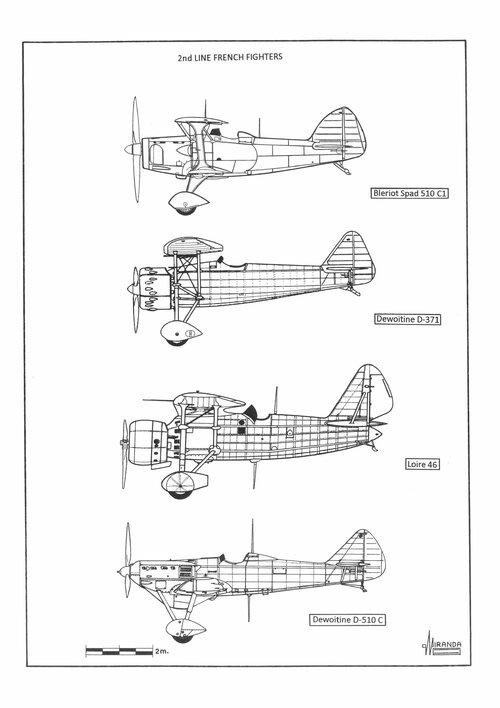

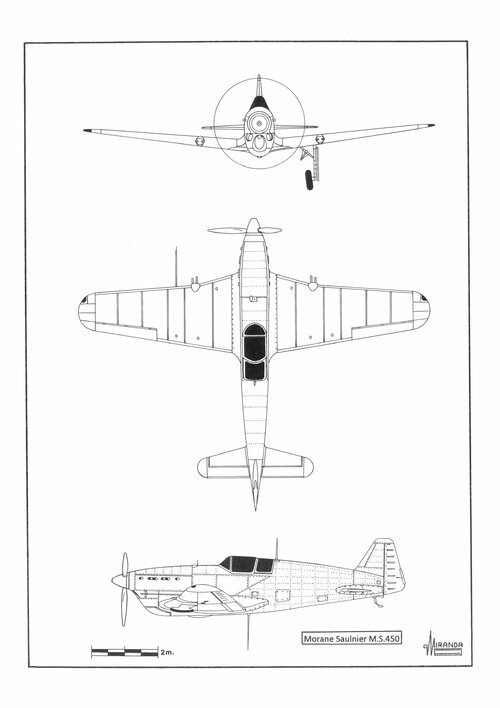

L'Armée de l'Air had only thirty-seven Bloch M.B.151, ninety-three Bloch M.B.152, ninety-eight Curtiss H.75A, two-hundred-and-seventy-eight Morane-Saulnier M.S.406 and sixty-seven Potez 631 fighters

bons de guerre, supported by thirty Gloster Gladiators and forty-eight Hurricanes British fighters. During the Battle of France 1,279 German, 872 French and 944 British airplanes were destroyed by different causes.

One of the main reasons for the success of the

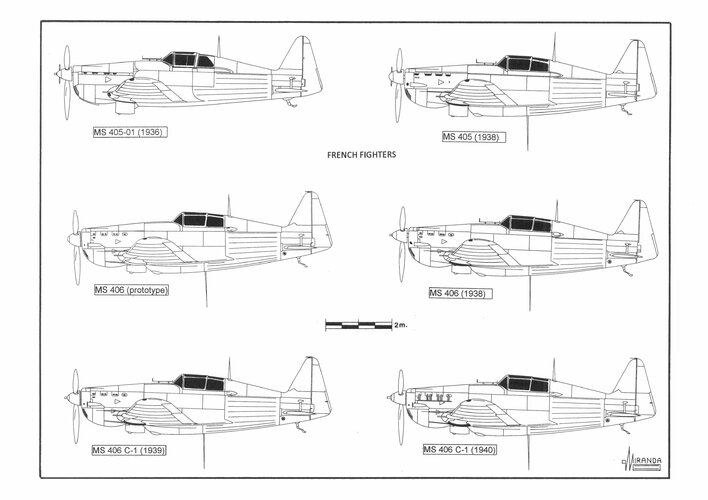

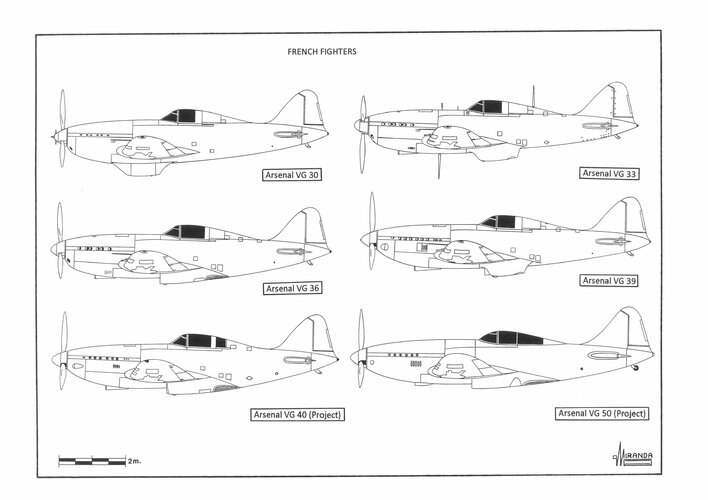

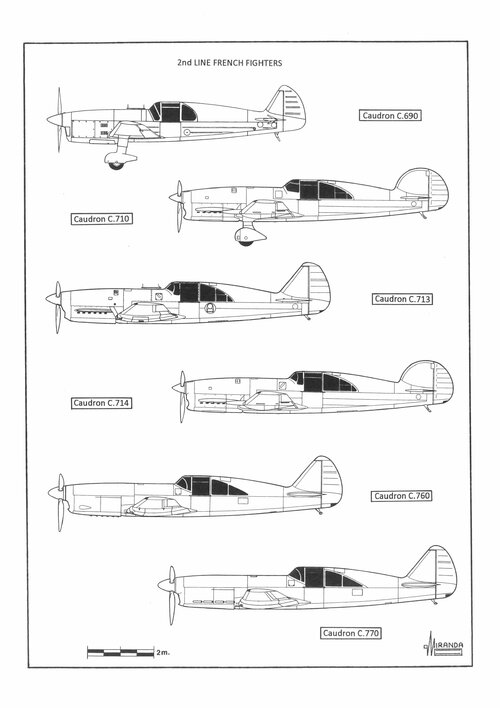

Blitzkrieg against the French and British Armies, in May 1940, was the aerial superiority obtained when the Messerschmitt Bf 109 E-3 entered service with the Luftwaffe. It happened at the right time, when the main French fighter Morane-Saulnier M.S.406 was replaced by the second generation fighters Dewoitine D.520 and Arsenal VG 33. During the

Phoney War,

l’Armée de l’Air tried to fill the gap with the Bloch M.B.152 and Curtiss H.75A fighters, helped by the British Hawker Hurricane Mk.I. But the Messerschmitt would prove superior.

This seems to be the origin of the commonly accepted paradigm about the assumed inferiority of the French technology. It is not common knowledge that France already had operational naval radar in 1934. And that, at the beginning of June 1940, the antiaircraft artillery defending Paris was controlled by the most advanced radar in the world, able to operate in wavelengths from 80 to 16 cm against the 3.5 to 1.5 m of the British or the 2.4 m to 53 cm of the German radar.

The French scientists were also ahead of their German equivalents in the field of nuclear fission. By early 1940, the CNRS controlled the highest reserve in the world of uranium (8 tons coming from the Belgian Congo) and 200 kg of heavy water from the Norwegian enterprise

Norsk Hydro.

The French tanks of 1940 had better armour and armament than the Germans. The

Marine Française (the French combat fleet) was superior to the

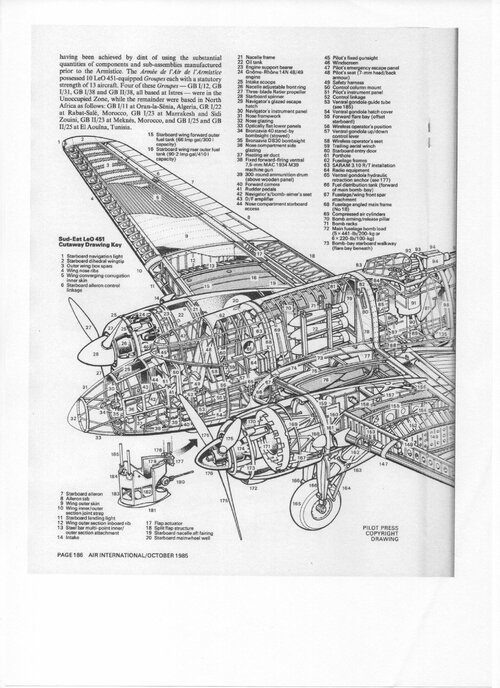

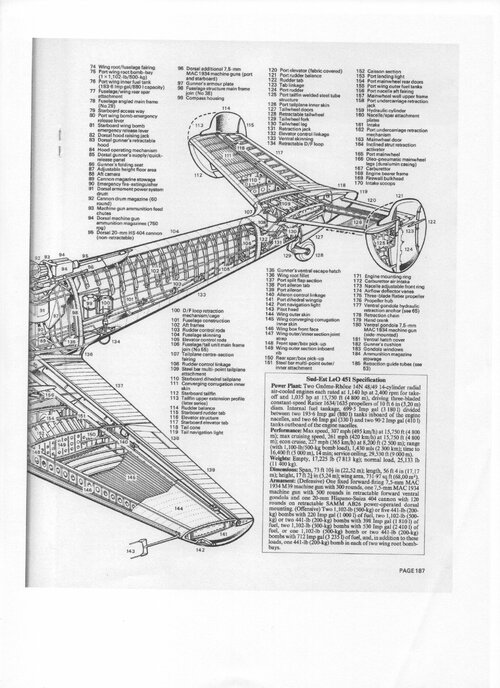

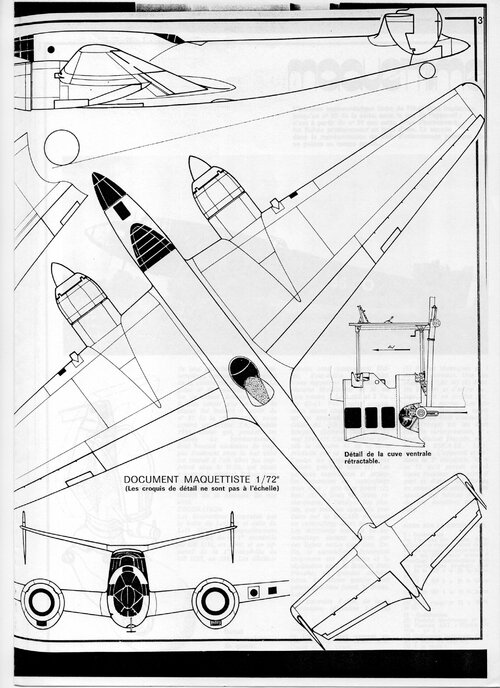

Kriegsmarine in firepower with the

Béarn carrier and six squadrons of Loire Nieuport L.N.401/411 dive bombers that technically surpassed the German Ju 87.

The destructiveness of the air-to-air weapons installed in the French fighters was slightly higher that their German equivalents, although the quality of the aiming devices OPL 31, RX 39 and GH 38 used by

l’Armée de l’Air was somehow inferior to the Zeiss

Revi C/12 reflector gunsight of the Luftwaffe. The following text compares the armament used by the French and German fighters during the Battle of France.

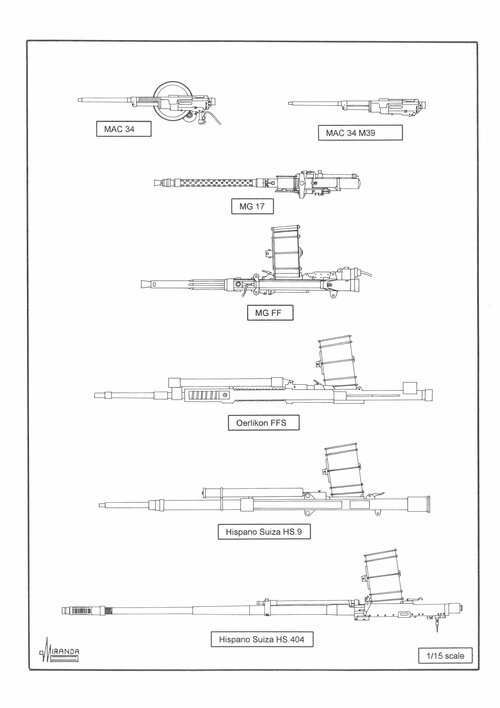

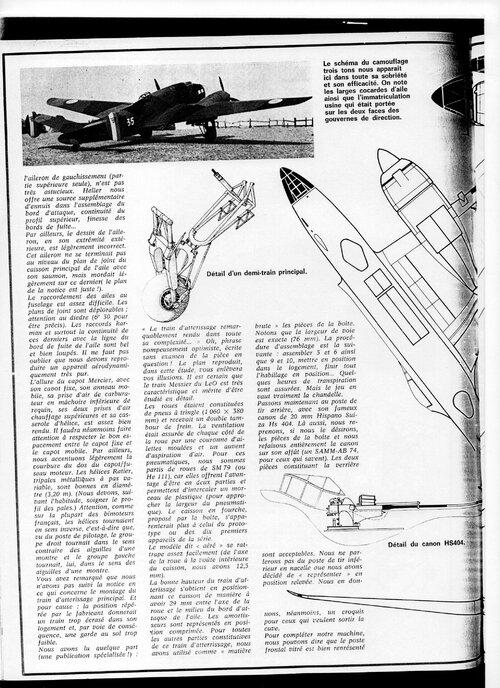

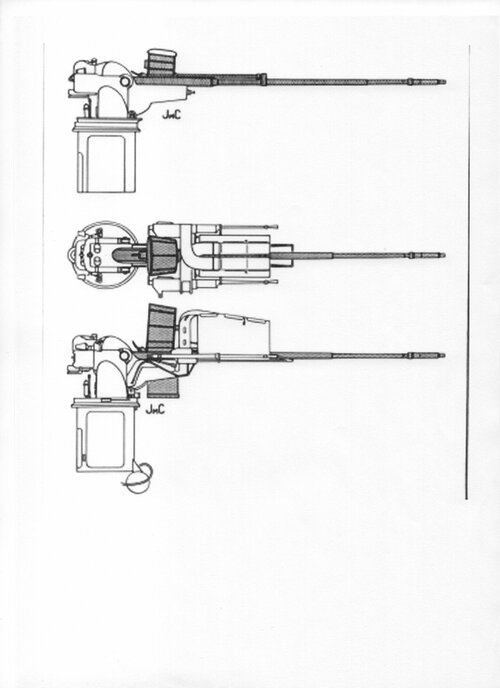

Ikaria MG FF (20 mm.)

During the 20s, the Swiss firm SEMAG committed itself to the design of the 20 mm gun Becker used during the WWI by some German bombers. During the first years of the 30s, the research was continued by the Swiss firm Oerlikon who, in 1933, started to commercialize three basic models using cartridges of progressive length and power. They were the Oerlikon FFF type (72 mm case length), the Oerlikon FFL type (100 mm case length) and the Oerlikon FFS type (110 mm case length).

The FFS was acquired by

l’Armèe de l’Air to serve as a base for its own Hispano Suiza H.S.7 and H.S.9 designs which were both modified for aircraft engine mounting. The FFL was acquired by the Imperial Japanese Navy in 1939 and manufactured under license from 1941 onwards, as 99-2 Type, to be used in the

Zero-Sen fighters. The FFF was chosen by the German, Polish and Romanian Air Forces to equip the Bf 109 E-2/E-3, Bf 110C, PZL P-24 C/F/G and IAR 80 fighters.

The Luftwaffe version was extensively modified to adapt the original design to the German production techniques, being mass manufactured by the

Ikaria Werke Berlin as MG FF (

Maschinen Gewehr Flügel Fest = Machine Gun Wing Installation) from 1935 onwards. It was the lightest short barrelled weapon in its class with just 28 kg. But it had a lower effective range and power of penetration than the contemporary French and Swiss designs.

These shortages were partially compensated by a higher rate of fire and the introduction of the MG FFM (

Modifizierung = Modification) which could fire the HE ammunitions

Minengeschoss.

It is unclear if the MG FFM was ever used during the Battle of France. Some authors state that the Bf 109 E-2 were armed with four MG 17 machine guns and at 20 mm cannon located behind the engine, firing through the axis of the hub propeller. As per this version of facts, the 'M' meant

Motor.

The Bf 109 E-2 passed through some operational tests with discouraging results because of the strong vibrations that the cannon produced in the engine crankcase during firing. Apparently, the decision to mount the two cannons in the wings of the Bf 109 E-3 went against the initial German project that preferred the French

moteur-canon device. This system was eventually adopted as a matter of urgency after the failure of the Bf 109 E-2 to alleviate the big difference in firepower between the Bf 109 E-1 and the Morane and Hurricane fighters.

The MG FF fired 20 mm ammunition of the 20 x 80RB type that could be HE (134 g), HEI (115 g) or

M-Geschoss (92 g). When installed in the Bf 109 E and Bf 110 C fighters of, it used a 60 rounds drum while the Do 17Z night fighters used a 15-45 rounds drum which could be manually replaced in combat. The Luftwaffe always considered the MG FF a transition weapon to fill the gap until the excellent MG 151 was available.

Oerlikon FFS (20 mm)

A small amount of these guns, together with their manufacturing license, was acquired by France in 1933. The FFS was not suitable for aircraft engine mounting because of the too advanced position of the recovery cylinder/yoke unit and had to be modified as Hispano-Suiza H.S.7. The French developed the SPAD S.XII in 1916 for the destruction of balloons. It was armed with a single-shot SAMC (APX) 37 mm cannon mounted between the V8 cylinder blocks of the 200 hp Hispano-Suiza 8c engine.

The

moteur-canon was not very successful, due to its slow reloading capacity and excessive recoil shock, and the SPAD S.XII was abandoned, but the French retained the idea until the arrival of the right time. This came in 1932 with the 690 hp liquid-cooled engine Hispano-Suiza H.S.12 Xbrs of 12 cylinders in 60º 'Vee' configuration.

This was the right engine to combine with one 20 mm Oerlikon FFS cannon -manufactured under license as Hispano-Suiza H.S.7- mounted between the two-cylinder banks. The crankcase was strengthened, and the reduction gear modified to bring the hollow propeller shaft in line with the gun barrel.

The ammunition was the same than that of the Swiss gun, contained in a 60 rounds drum. The H.S.7 was heavier, due to the fixation system to the engine, and had a rate of fire of just 350 rpm (compared to the 470 rpm of the Oerlikon) to protect the engine from any destructive vibration. This engine was then known as Hispano-Suiza 12 Xcrs (‘c’ for

canon = cannon) and had reduced its power to 680 hp, consequence of the modifications made in the gearbox. The new

moteur-canon was installed in the Dewoitine D.510 fighter and in the Loire-Nieuport L.N. 401/411 dive bombers of

l’Aeronavale which fought the panzers on 15 May 1940.

The Germans tried to use the

moteur-canon system with their Bf 109 V4, C-2 and E-2 fighters, trying different combinations of Jumo 210 and Daimler Benz 601 engines with MG 17 machine guns and MG FF cannons. But they found insoluble problems of cooling and crankcase destructive vibrations. On October 1940, they finally adapted an MG FF cannon behind the DB 601N engine of the Bf 109 F-0, but the device suffered structural damages during tests. The problem could not be solved until the MG 151/20 gun was available and could be installed in the Bf 109 F-2 in March 1941.