NEWS | JULY 8, 2019

A New Plan for Keeping NASA's Oldest Explorers Going

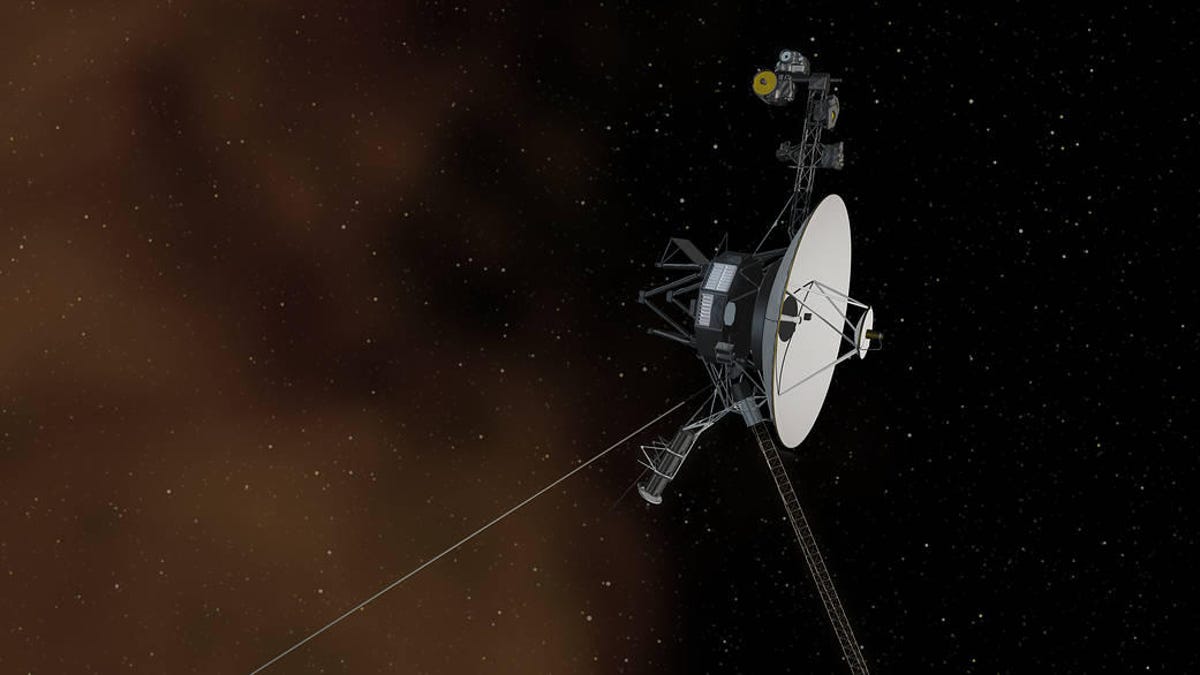

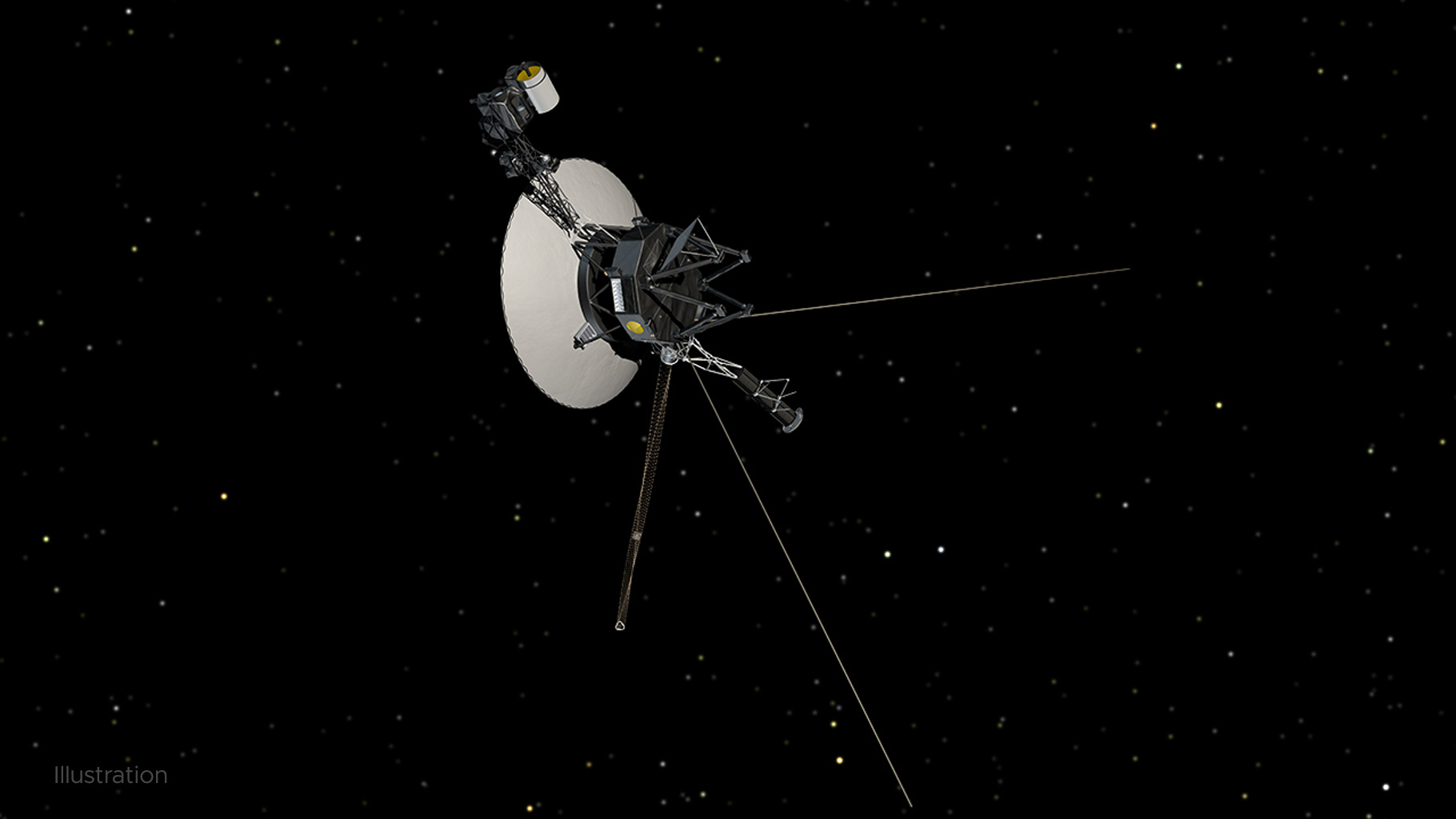

With careful planning and dashes of creativity, engineers have been able to keep NASA's Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft flying for nearly 42 years - longer than any other spacecraft in history. To ensure that these vintage robots continue to return the best science data possible from the frontiers of space, mission engineers are implementing a new plan to manage them. And that involves making difficult choices, particularly about instruments and thrusters.

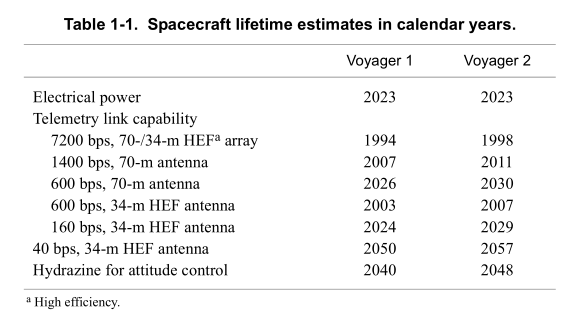

One key issue is that both Voyagers, launched in 1977, have less and less power available over time to run their science instruments and the heaters that keep them warm in the coldness of deep space. Engineers have had to decide what parts get power and what parts have to be turned off on both spacecraft. But those decisions must be made sooner for Voyager 2 than Voyager 1 because Voyager 2 has one more science instrument collecting data - and drawing power - than its sibling.

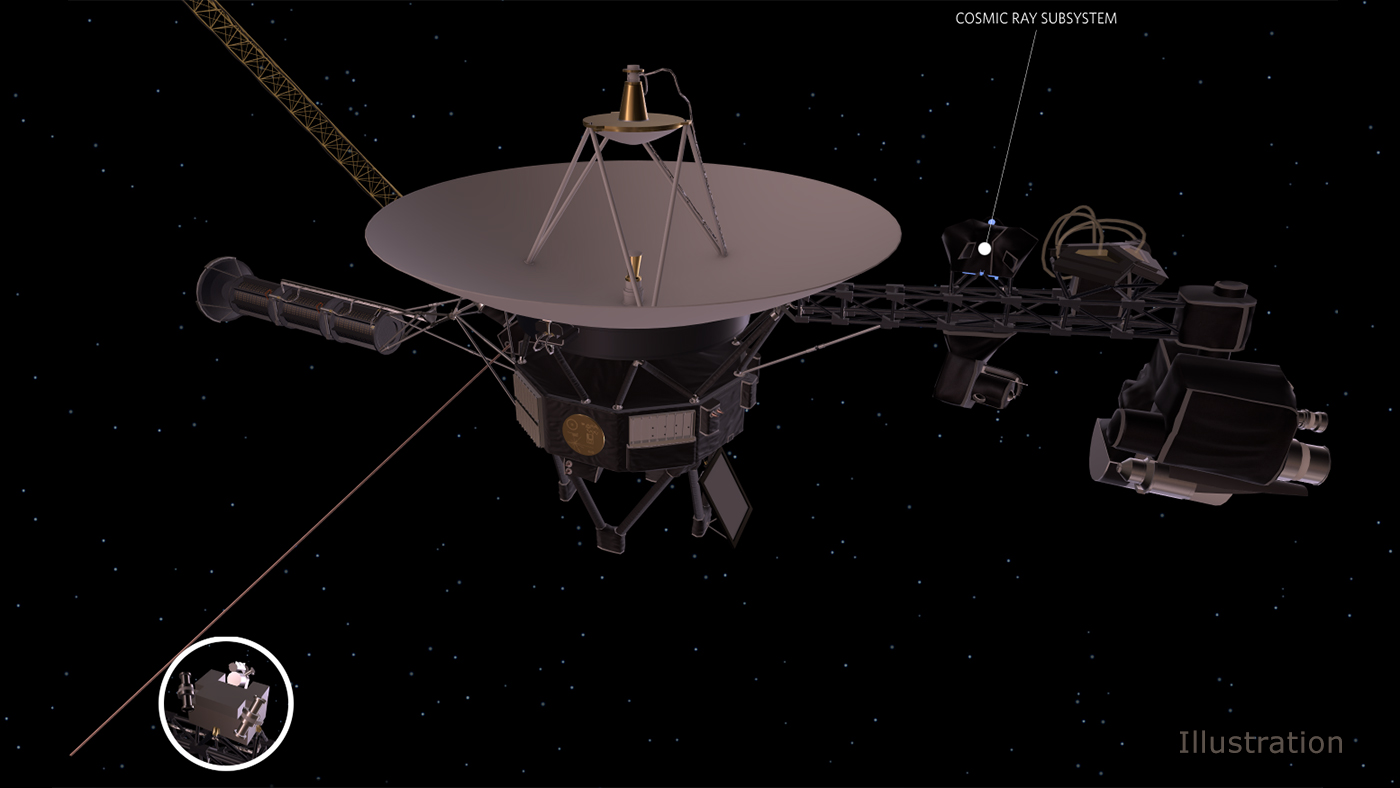

After extensive discussions with the science team, mission managers recently turned off a heater for the cosmic ray subsystem instrument (CRS) on Voyager 2 as part of the new power management plan. The cosmic ray instrument played a crucial role last November in determining that Voyager 2 had exited the heliosphere, the protective bubble created by a constant outflow (or wind) of ionized particles from the Sun. Ever since, the two Voyagers have been sending back details of how our heliosphere interacts with the wind flowing in interstellar space, the space between stars.

Not only are Voyager mission findings providing humanity with observations of truly uncharted territory, but they help us understand the very nature of energy and radiation in space - key information for protecting NASA's missions and astronauts even when closer to home.

Mission team members can now preliminarily confirm that Voyager 2's cosmic ray instrument is still returning data, despite dropping to a chilly minus 74 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 59 degrees Celsius). This is lower than the temperatures at which CRS was tested more than 42 years ago (down to minus 49 degrees Fahrenheit, or minus 45 degrees Celsius). Another Voyager instrument also continued to function for years after it dropped below temperatures at which it was tested.

"It's incredible that Voyagers' instruments have proved so hardy," said Voyager Project Manager Suzanne Dodd, who is based at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. "We're proud they've withstood the test of time. The long lifetimes of the spacecraft mean we're dealing with scenarios we never thought we'd encounter. We will continue to explore every option we have in order to keep the Voyagers doing the best science possible."

Voyager 2 continues to return data from five instruments as it travels through interstellar space. In addition to the cosmic ray instrument, which detects fast-moving particles that can originate from the Sun or from sources outside our solar system, the spacecraft is operating two instruments dedicated to studying plasma (a gas in which atoms have been ionized and electrons float freely) and a magnetometer (which measures magnetic fields) for understanding the sparse clouds of material in interstellar space.

Taking data from a range of directions, the low-energy charged particle instrument is particularly useful for studying the probe's transition away from our heliosphere. Because CRS can look only in certain fixed directions, the Voyager science team decided to turn off CRS's heater first.

Voyager 1, which crossed into interstellar space in August 2012, continues to collect data from its cosmic ray instrument as well, plus from one plasma instrument, the magnetometer and the low-energy charged particle instrument.

Why Turn Off Heaters?

Launched separately in 1977, the two Voyagers are now over 11 billion miles (18 billion kilometers) from the Sun and far from its warmth. Engineers have to carefully control temperature on both spacecraft to keep them operating. For instance, if fuel lines powering the thrusters that keep the spacecraft oriented were to freeze, the Voyagers' antennae could stop pointing at Earth. That would prevent engineers from sending commands to the spacecraft or receiving scientific data. So the spacecraft were designed to heat themselves.

But running heaters - and instruments - requires power, which is constantly diminishing on both Voyagers.

Each of the probes is powered by three radioisotope thermoelectric generators, or RTGs, which produce heat via the natural decay of plutonium-238 radioisotopes and convert that heat into electrical power. Because the heat energy of the plutonium in the RTGs declines and their internal efficiency decreases over time, each spacecraft is producing about 4 fewer watts of electrical power each year. That means the generators produce about 40% less than what they did at launch nearly 42 years ago, limiting the number of systems that can run on the spacecraft.

The mission's new power management plan explores multiple options for dealing with the diminishing power supply on both spacecraft, including shutting off additional instrument heaters over the next few years.

Revving Up Old Jet Packs

Another challenge that engineers have faced is managing the degradation of some of the spacecraft thrusters, which fire in tiny pulses, or puffs, to subtly rotate the spacecraft. This became an issue in 2017, when mission controllers noticed that a set of thrusters on Voyager 1 needed to give off more puffs to keep the spacecraft's antenna pointed at Earth. To make sure the spacecraft could continue to maintain proper orientation, the team fired up another set of thrusters on Voyager 1 that hadn't been used in 37 years.

Voyager 2's current thrusters have started to degrade, too. Mission managers have decided to make the same thruster switch on that probe this month. Voyager 2 last used these thrusters (known as trajectory correction maneuver thrusters) during its encounter with Neptune in 1989.

Many Miles to Go Before They Sleep

The engineers' plan to manage power and aging parts should ensure that Voyager 1 and 2 can continue to collect data from interstellar space for several years to come. Data from the Voyagers continue to provide scientists with never-before-seen observations of our boundary with interstellar space, complementing NASA's Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX), a mission that is remotely sensing that boundary. NASA is also preparing the Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP), due to launch in 2024,to capitalize on the Voyagers' observations.

"Both Voyager probes are exploring regions never before visited, so every day is a day of discovery," said Voyager Project Scientist Ed Stone, who is based at Caltech. "Voyager is going to keep surprising us with new insights about deep space."

The Voyager spacecraft were built by JPL, which continues to operate both. JPL is a division of Caltech in Pasadena. The Voyager missions are a part of the NASA Heliophysics System Observatory, sponsored by the Heliophysics Division of the Science Mission Directorate in Washington. For more information about the Voyager spacecraft, visit:

Voyager 1 and its twin Voyager 2 are the only spacecraft ever to reach the edge of interstellar space..

www.nasa.gov

Voyager 1 and its twin Voyager 2 are the only spacecraft ever to reach the edge of interstellar space..

voyager.jpl.nasa.gov