Small nuclear reactors could power "cleaner" ships

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

29 March 2011 by John Webb, London Press Service

Environment & Energy » Energy

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

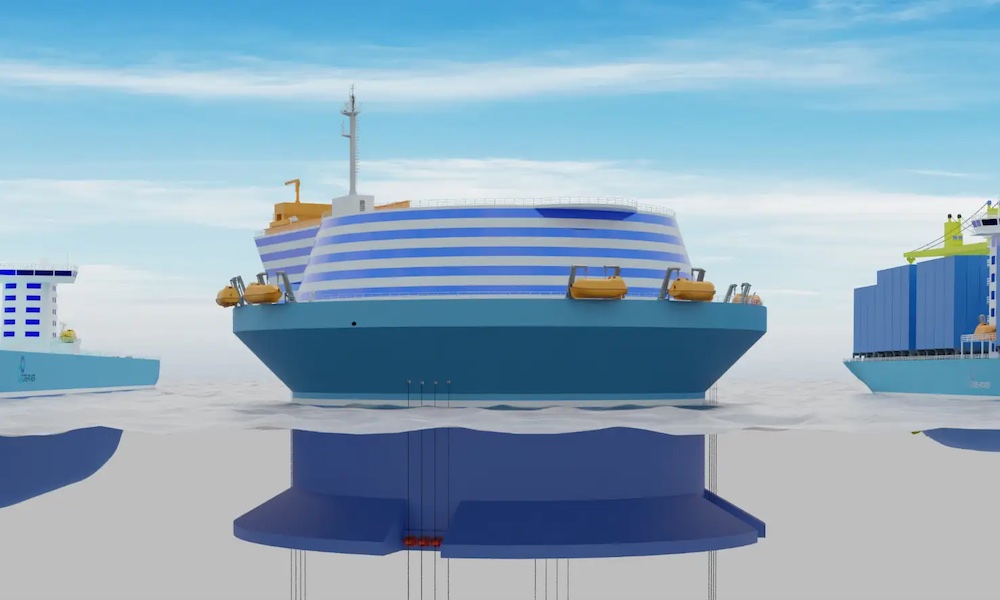

Image by Babcock Marine; UK proposes the use of small nuclear reactors to power surface vessels such as gas tankers to minimise CO2 emissions.

Small nuclear reactors could power "cleaner" ships. Consortia of organisations are looking at the feasibility of nuclear propulsion for commercial tankers.

Shipping and power industry experts are joining forces to explore the potential of small modular nuclear reactors to drive future generations of commercial tankers - to help make the seas cleaner.

Together - the group from the UK, the US and Greece - will probe the practical maritime applications for nuclear propulsion that they believe is technically feasible and has the potential to drastically reduce the CO2 emissions caused by commercial shipping.

The consortium is led by Lloyd’s Register of London, UK ship-design consultancy BMT Nigel Gee, the US Hyperion Power Generation group and Greek ship operator Enterprises Shipping & Trading.

Richard Sadler, chief executive officer of Lloyd’s Register, which is one of the world’s largest ship classification societies, said: “This is a very exciting project. We believe that as society recognises the limited choices available in the low-carbon, oil-scarce economy - and as land-based nuclear plants become common place - we will see nuclear ships on specific trade routes sooner than many people currently anticipate.”

BMT’s sector transport director, Dr Phil Thompson, added: “Nuclear propulsion offers the opportunity for an emissions-free alternative to fossil fuel, while delivering ancillary benefits and security to the maritime industry.

“We look forward to using our wide range of maritime skills and expertise to identify the through-life implications, risks and potential for developing and using small modular reactors in the civilian maritime environment and to provide a framework for its safe and reliable introduction and utilisation.”

The consortium believes that such small modular reactors (SMRs) would ideally have a thermal power output of 68 megawatt (MW) or more and the potential to be used as a plug-in nuclear “battery.”

It is expected the research will centre on a sealed nuclear reactor that is small in both size and output to heat pressurised water and generate steam for turbines driving the propellers or generating electricity to power them.

The aim is to produce a concept SMR tanker-ship design based on conventional and modular concepts. Special attention will be paid to an analysis of a vessel’s life-cycle cost as well as to hull-form designs and structural layout, including grounding and collision protection.

Until now, the use of maritime nuclear reactors with power outputs ranging from 10 to 300MW has been largely confined to submarines and other types of naval vessels, including aircraft carriers.

The London-based World Nuclear Association said that work began on nuclear marine propulsion in the 1940s and the first test reactor started in the United States in 1953.

Some 140 vessels are now powered by more than 180 small nuclear reactors and over 12,000 reactor years of marine operation have been accumulated, mostly by submarines. The world’s first nuclear-powered surface vessel was Russia’s icebreaker Lenin, commissioned in 1959, which remained in service for 30 years.

Development of nuclear merchant ships began in the 1950s, led by the commissioning of the 22,000-tonne US-built Savannah in 1962. Although the first examples were a technical success they proved not to be economically viable.

But now international shipping has been identified as a significant global contributor to greenhouse gas emissions and operators are under mounting pressure to contribute to overall emissions reduction.

As a result, the World Nuclear Association believes there is renewed interest in marine nuclear propulsion. A spokesman said: “Nuclear power is particularly suitable for vessels which need to be at sea for long periods without refuelling.”

Such vessels would include large bulk carriers, cruise liners, nuclear tugs that would take conventional ships across oceans, and some types of bulk shipping where speed was essential.

While the two-year consortium research project gets under way, the marine division of the UK’s Babcock International Group recently completed a study of the commercial implications of developing a nuclear-powered liquefied natural gas carrier.

The projects director of the integrated technology unit of Babcock’s Marine Division, David Dobson, said the study has shown that particular routes and cargoes lend themselves well to the nuclear propulsion option, and technological advances in reactor design and manufacture have made the option more appealing.

He concludes: “Nuclear power for commercial vessels is becoming significantly more attractive on a number of counts, not least from an environmental perspective.”

Contact details:

Name: Nick Brown, Marine Communications Manager, Lloyd’s Register

Website: www.lr.org

Telephone: +44 (0)20 74231706

Email: nick.brown@lr.org

Address: Lloyd’s Register, 71 Fenchurch Street, London, United Kingdom EC3M 4BS

http://www.londonpressservice.org.uk/lps/environmentenergy/item/128747.html