I was a student at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Daytona Beach, Florida at the time, and was awake until around 3 a.m. the night prior to the launch. If I wanted to drive to Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in time to see the planned 9:30 a.m. liftoff, I knew that I wouldn’t get much sleep, and I was scheduled to take a test at noon. Someone asked why I was still planning to go and I confessed I didn’t know. “It’s just another shuttle launch,” I said. But, I didn't want to miss it.

A few hours later I drove to Titusville where I joined a long line of cars heading for NASA Causeway East. Normally, it was necessary to request a causeway access pass well in advance. I had failed to do this, but decided to take a chance. Upon reaching the NASA security checkpoint, I was surprised when a guard handed me a pass and told me to proceed.

After parking, I joined a throng of enthusiastic tourists and space buffs undeterred by the cold weather. I will never forget the bitterly cold temperatures, around 36 degrees as I recall. The sky was a spectacular cerulean blue, cloudless and seemingly infinite. When liftoff was delayed two hours due to failure of a component in the launch processing system used to monitor the fire detection system, I decided to huddle in my car until the final five minutes of the countdown. At that point, I braced myself against the icy wind and waited.

Excitement built to a crescendo in the final moments as the launch announcer called out the countdown. “Ten, nine, eight!” Billowing steam clouds signaled main engine start. “Three, two, one, zero!”

All along the causeway, people began to shout and clap. I was about six miles from the launch pad. Even travelling at more than 700 miles per hour the sounds of liftoff took nearly 10 seconds to roll across the frigid water to challenge the cheering voices.

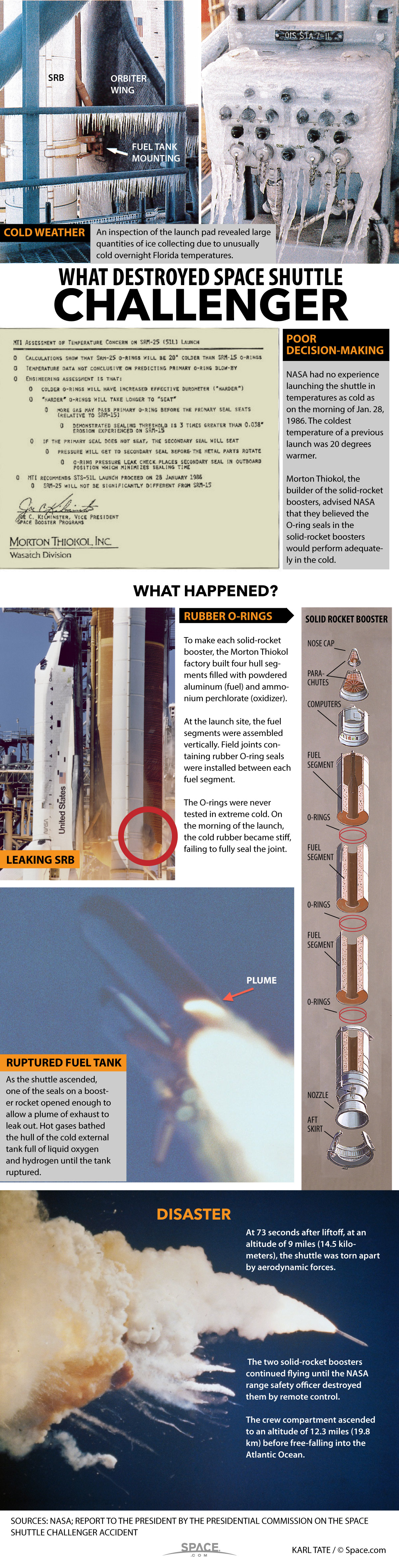

At first everything looked normal but then the vehicle’s white smoke trail suddenly blossomed into a brownish-orange ball. The two solid-fuel booster rockets split away in opposite directions before ultimately establishing parallel trajectories as if flying in formation. Various smaller objects emerged from the expanding cloud, each ascending with its own white vapor trail. Seconds later, both boosters disappeared in twin flashes of fiery yellow.

A woman next to me shouted, “Look, booster separation!” I knew, however, that it was too soon for that. At this point in the flight, Challenger would have not yet have reached 50,000 feet. “No,” I told her, “something is very, very, wrong.”

The NASA public address system had fallen silent. As people began to realize what had happened, some cried out in anguish. I watched various small objects tumbling toward the ocean, trailing white streamers. Challenger’s smoke trail, brilliant white against azure, ended in a twisted mushroom cloud. Debris particles, like a snowstorm of glitter, fell for nearly an hour. Disbelieving eyes scanned the sky for an orbiter that would not return. Fingers pointed in forlorn hope at a white parachute that I recognized as part of a booster rocket.

Driving back to Embry-Riddle was a surreal experience. The smiling attendant at the toll bridge south of KSC didn't seem to have heard the news. Back on campus a few hours later, I could still see the smoke trail hanging in the sky. I had missed my test, but my instructor said I could reschedule. I don't remember much about the scramble to redo the Avion issue, at least not specific details, but I will never forget that day.

jalopnik.com