Nearly final installment on details of the Lockheed L-610 C-X proposal, submitted in January 1981.

As promised, I completed my clean-up of some old graphics showing the details of the cargo box of the L-610. At an overall length (including the fully loadable cargo ramp) of 90.4 feet, the cargo box of the smaller and lighter L-610 was actually 1.6 feet longer than the box of the C-17A (88 feet, including the ramp). The flexibility of the L-610 box is shown in the first PDF that includes illustrations of several cargo and vehicle load-outs from the proposal.

The second PDF shows the L-610 fuselage cross section in detail. Nearly the whole fuselage is a pressure vessel with the main circular lobe having a radius of 131 inches, while the lower lobe (essentially the cargo floor strong-back) has a radius of 212 inches. This cross section compares favorably to other airlifters of the day (see the third PDF for reference).

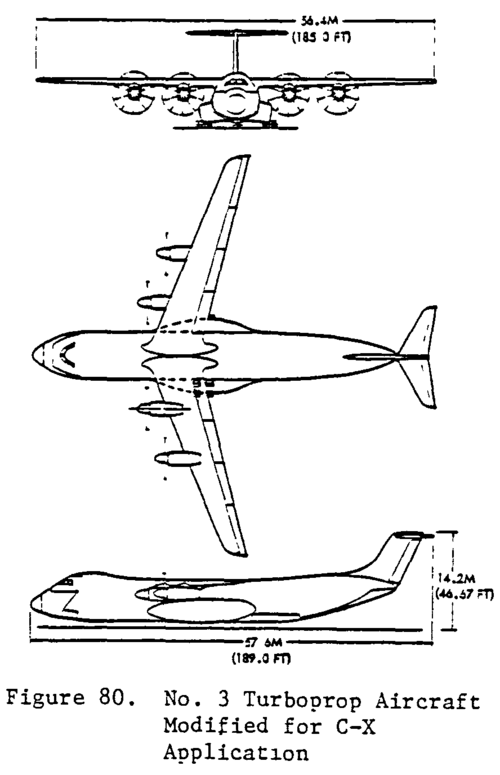

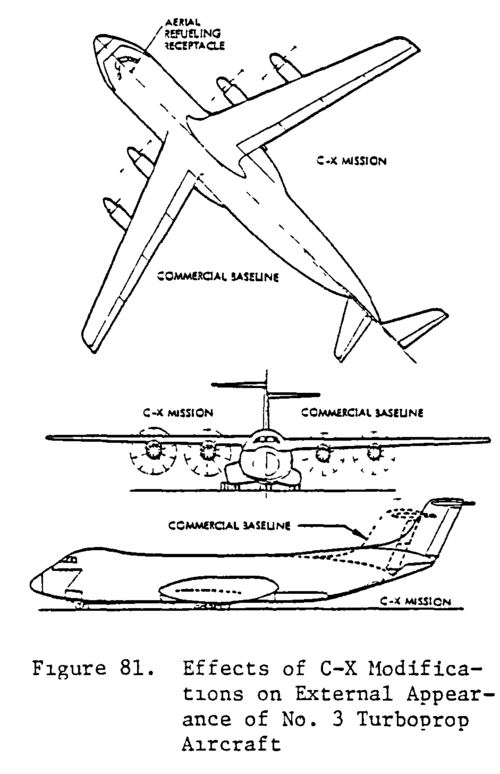

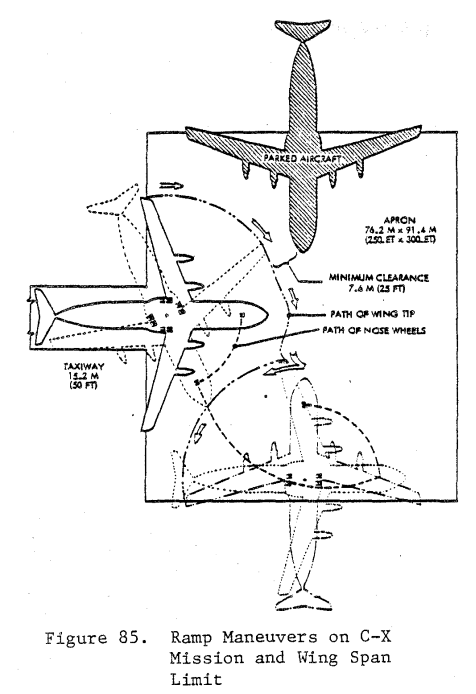

The fourth PDF is a direct comparison of the L-610 cross section to the C-17A, with the C-5A for reference. This shows that the L-610 had a slimmer cross section (lower drag) with a similar (and even taller) cargo box. As I mentioned previously, cargo box dimensions and max cargo weight requirements were not directly specified in the C-X RFP. Bidders justified their designs as optimized for minimum overall life-cycle cost to do the design mission. That requirement was to fly, using an unspecified number of aircraft, a specified Army mechanized unit 2800 NM (unrefueled) to an austere 3000-foot semi-prepared airfield, carrying a minimum of 100,000 lb of cargo per aircraft. The aircraft size, and therefore number, were constrained by how many could fit at any given time on a fixed size cargo-apron tarmac. (Incidentally, this tarmac size severely limited wing span, driving the heavier C-17A design to employing winglets, always an aerodynamicist's second-choice to increased span when otherwise not constrained.) Lockheed's C-X approach was the L-610 with a design cargo weight of 100,000 lb at a load factor of 2.5 g (max cargo weight of 130,000 lb, at 2.25 g), while McDonnell Douglas opted for the heavier C-17A with a design cargo weight of 160,000 lb (max of 170,900 lb).

The fifth PDF is a direct comparison of the L-610 cross section to the proposed C-130WBS ("Wide Body STOL"), an alternative proposal during the AMST days. This graphic shows how the Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicle was a dimensional driver for tactical airlifter designs in the 1970s and 1980s.

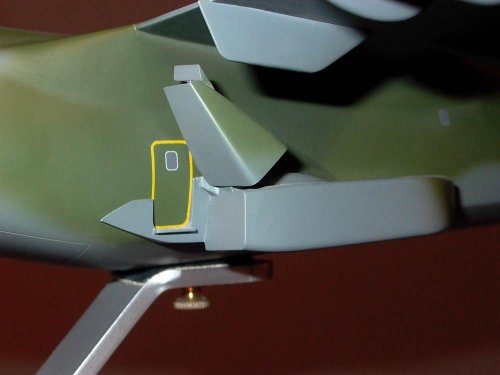

The sixth and final PDF of this post highlights another design tradeoff featured in the L-610. The main landing gear (a "high flotation" design featuring eight wheels on each leg) was housed completely external to the fuselage pressure vessel. The weight savings in fuselage structure offsetting the greater drag of the more pronounced landing gear pods ("wheel well fairings" would be a misnomer, since there was no "well" inside the fuselage for the main landing gear). The main landing gear bogie is actually two trailing-arm levered suspension units back-to-back on one leg. That allowed for maintenance on the ground (tire changes and brake work) by self-jacking. One levered arm could be raised under its own power, independent of the other, to lift four of the eight wheels off the ground without having to place the whole aircraft on jacks.

I have a few overall comments for one more post.