- Joined

- 11 June 2014

- Messages

- 1,541

- Reaction score

- 2,899

Secret Projects of the Luftwaffe. Volume 3: Messerschmitt Me 262,

MESSERSCHMITT ME 262: DEVELOPMENT AND POLITICS | Mortons Books

Book - Messerschmitt Me 262: Development and Politicswww.mortonsbooks.co.uk

was announced until recently at mortons for 14.99£ with 116 pages. Now it is listed on their site for 30£ and 300 pages. Does anyone have any info what happened there?

The original concept for the book was to rattle through the different 'secret projects' variants - setting them in context and describing them. I thought this would take about 25,000-30,000w and fit nicely into my Secret Projects of the Luftwaffe series as volume 3. I wouldn't be looking at the squadrons, the combat, the production - just the projects. As with my other books, I intended to base my writing solely on cited primary sources.

The Me 262 has been covered in so many books - usually with the 'projects' compiled into a single chapter or just listed. But those chapters/lists usually provide little or no timescale and little or no context, except where a variant was actually built and even more where it was built and used in combat.

The more I researched the Me 262's development, the more I realised that there was a huge story behind every single variant schemed. And in some cases, every single book on the Me 262 had got it wrong - including the Smith/Creek books which are otherwise the gold standard in Me 262 histories (although, crucially, they don't list their sources).

Take the Me 262 A-1a/U1 for example. Up till now, everyone has thought that this variant was intended to have six guns - 2 x MK 108 + 2 x MK 103 + 2 x MG 151. Doesn't this strike you as weird? Why? Why would anyone think that putting three different weapons in a single nose was a good/viable idea? Apparently literally nobody has ever questioned this before. When I came to look at the primary source material, it was immediately evident that the armament planned for the Me 262 A-1/U1 was 2 x MK 103 + 2 x MK 108 or 2 x MG 151. It was a four gun nose and there was simply a question mark over whether an MK 103/MK 108 or MK 103/MG 151 layout was better.

A test mule nose was made housing six guns purely so that 2 x MK 108 + 2 x MK 103 could be fired together, then 2 x MK 103 + 2 x MG 151 could be fired together without having to build a separate nose or swap the guns in and out. There was only one fuselage on the test range to which the nose could be attached and putting all the guns into one nose saved time. No-one ever seems to have been aware of this before.

And that's just the tip of the iceberg. Why was the Me 262 A-2/U2 originally designated Me 262 A-3? Why did they bother with a prone bombardier nose when they could've converted an Me 262 B-1 to create a bombardier position behind the pilot? It turns out that's exactly what Galland wanted, it's what Peltz wanted, and it's what Messerschmitt's project office thought was best. So why wasn't that variant built?

Why does everyone think that it was an acceptable idea to create a Mistel combination of two Me 262s or an Me 262 and a Ju 287? Jet aircraft and jet engines were in desprately short supply. Surely it would be crazy to plan on wasting one like that when there were so many life-expired airframes of other types lying around. And indeed this appears to have been the case. The primary sources all show that the Mistel 4 was an Me 262 paired with a Ju 88 - the Ju 88 getting a TV camera to account for the difference in speed after launch. But there is a known drawing of the 262/262 arrangement and not of the 262/88 arrangement. Could it be that every previous history of the 262 has been based on drawings rather than text documents?

And the list goes on. Every man and his dog has a theory about how much Hitler interfered in the Me 262's development, why the type was late into service (was it the engines? was it the bombs?). Nobody has ever presented a full explanation backed up by primary source material. I realised that I have sufficient primary sources to definitively answer that question.

So the 25,000-30,000w book became, over the course of a year, a 150,000w hardback. It still doesn't include anything on combat or the units - but it does provide a full development history, giving context and background for every variant based on fully cited and referenced primary sources.

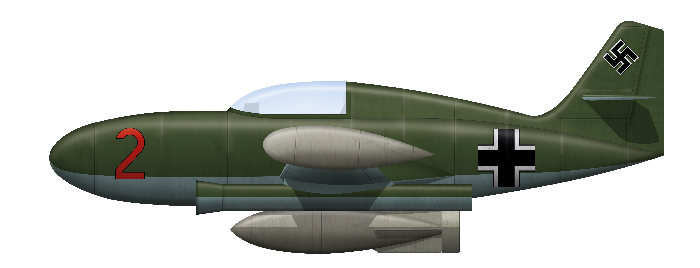

I think anyone who reads it will be shocked to discover how much they didn't know about the Me 262. In terms of project status, I've just finished incorporating details of five Protokoll documents produced during the last days of March 1945 and I'm about to start on preparing the illustrations and captions. In other words, it's not far off being ready for the designer.

Last edited: