- Joined

- 29 July 2009

- Messages

- 1,768

- Reaction score

- 2,473

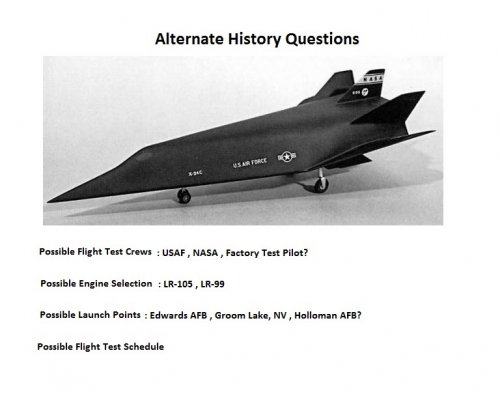

This is just a little thought exercise in a 'what-if' scenario for a hypersonic flight research program.

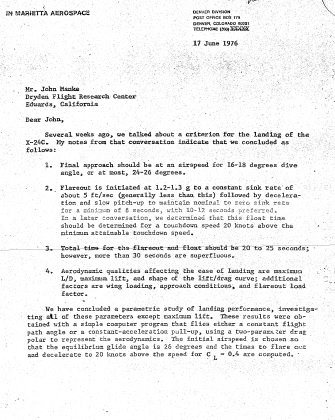

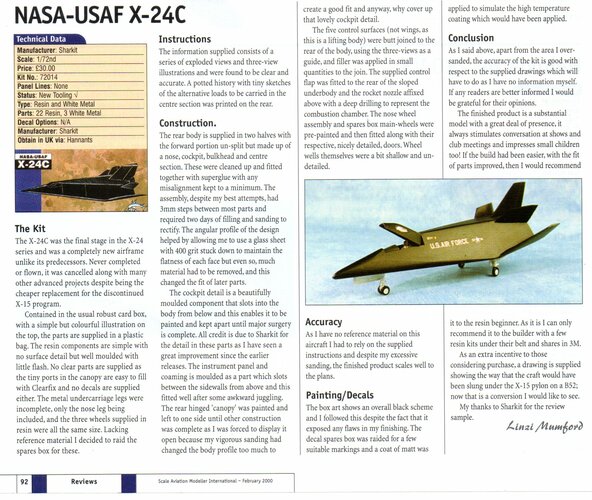

The US efforts to develop a hypersonic aircraft design in the 1950's (Aerospaceplace, X-15), 1960's (X-20, Lifting Bodies), and 1970's (X-24C, HYFAC) culminated, for a time, in the USAF and NASA X-24C project, which would have been a follow-on to the X-24A/B, HL-10, M2-F1/2/3, etc.

With what we know of the X-24C program this alternative history examines the questions of:

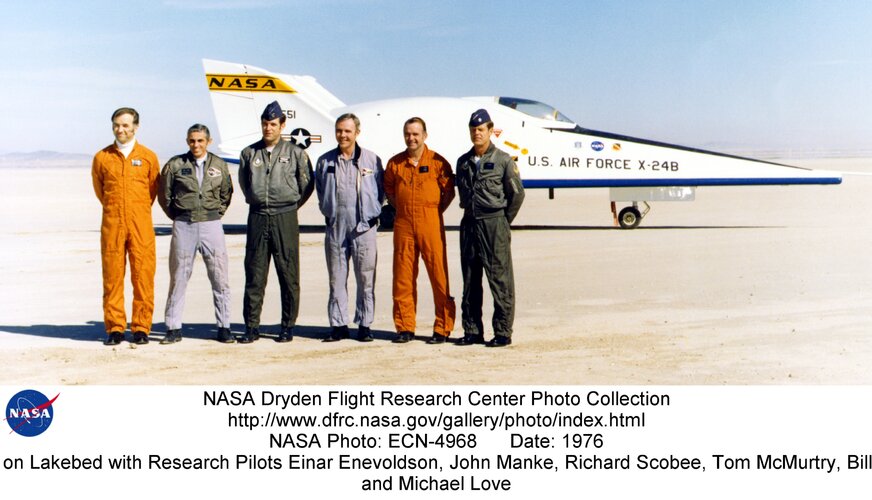

1. Which project pilots (USAF, NASA, and Contractor) would have been the likely candidates to have flown the aircraft during the projected timeframe?

2. Which manufacturer had the lead in receiving the contract (i.e. McAir or Lockheed)?

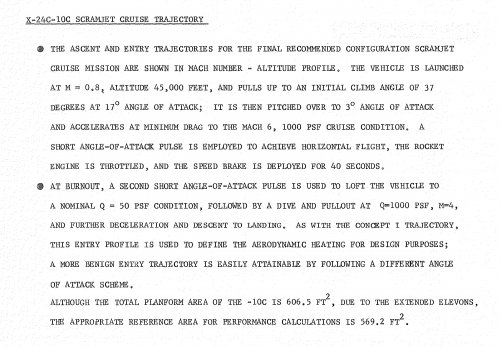

3. Which engine combination was likely the one to be used, or both in a program designed for growth?

4. Where there any additional configurations that might have been best to consider in the program (drop tanks, different carrier aircraft, fin arrangement, etc.)?

5. Which launching station would have been used and would Groom Lake have been considered as a recovery site?

6. Which experiments would have likely flown?

7. Where could the program have gone after the X-24C (e.g. X-24D)?

The US efforts to develop a hypersonic aircraft design in the 1950's (Aerospaceplace, X-15), 1960's (X-20, Lifting Bodies), and 1970's (X-24C, HYFAC) culminated, for a time, in the USAF and NASA X-24C project, which would have been a follow-on to the X-24A/B, HL-10, M2-F1/2/3, etc.

With what we know of the X-24C program this alternative history examines the questions of:

1. Which project pilots (USAF, NASA, and Contractor) would have been the likely candidates to have flown the aircraft during the projected timeframe?

2. Which manufacturer had the lead in receiving the contract (i.e. McAir or Lockheed)?

3. Which engine combination was likely the one to be used, or both in a program designed for growth?

4. Where there any additional configurations that might have been best to consider in the program (drop tanks, different carrier aircraft, fin arrangement, etc.)?

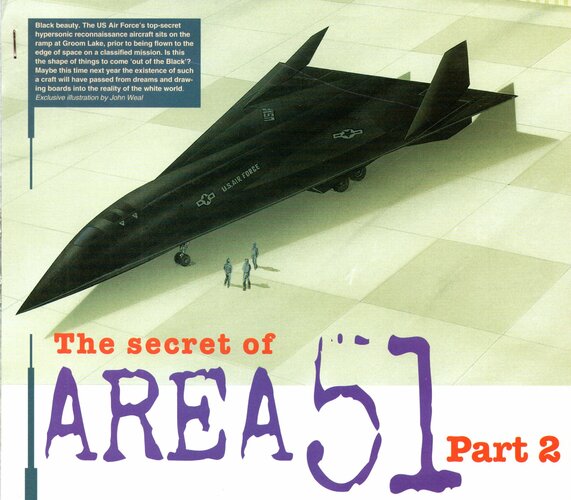

5. Which launching station would have been used and would Groom Lake have been considered as a recovery site?

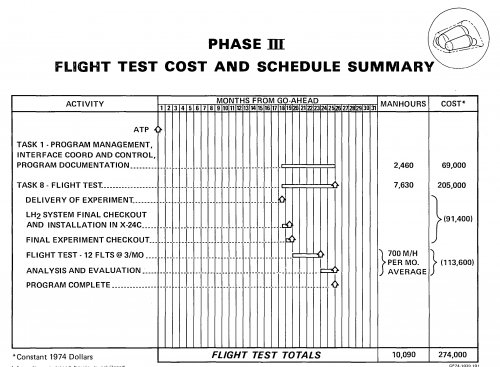

6. Which experiments would have likely flown?

7. Where could the program have gone after the X-24C (e.g. X-24D)?