Does anyone have any additional information on the proposed Royal Dockyard at Northfleet?

Royal Dockyards by Philip MacDougall Pages 134 – 136.

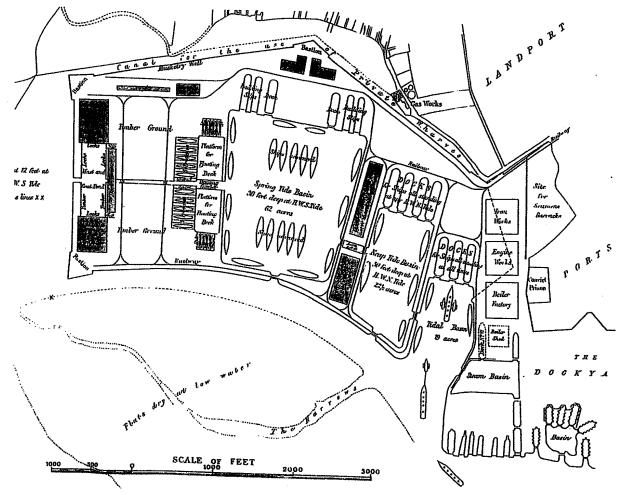

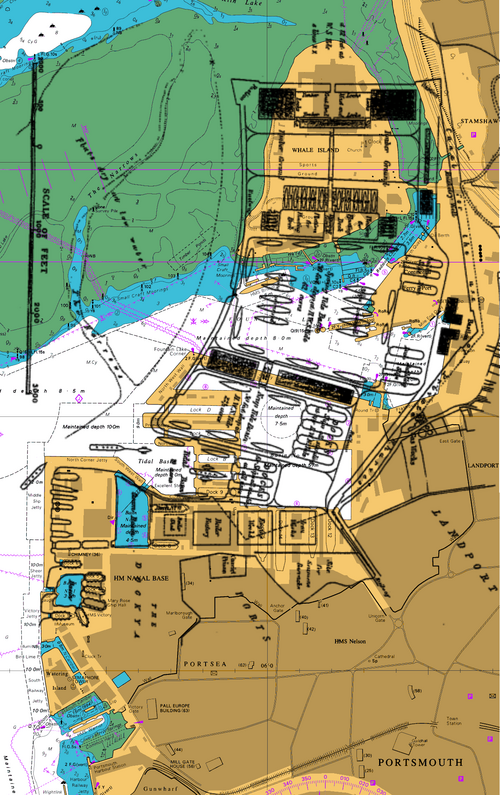

In the light of John Rennie’s great experience as an engineer, it is interesting to consider observations he made on various royal yards in 1807. These were prompted by a commission of enquiry that had been set up to examine defect in all naval establishments. Rennie was singularly unimpressed; he considered Plymouth to be the most suited, noting the spacious harbour, general lack of silting and the navigational hazards that would eventually be overcome by the breakwater. Portsmouth, on the other hand, was more heavily criticized for, at that stage, the harbour was showing definite signs of silting, whilst he considered the dockyard to lack adequate space for the various buildings and machine shops being built.

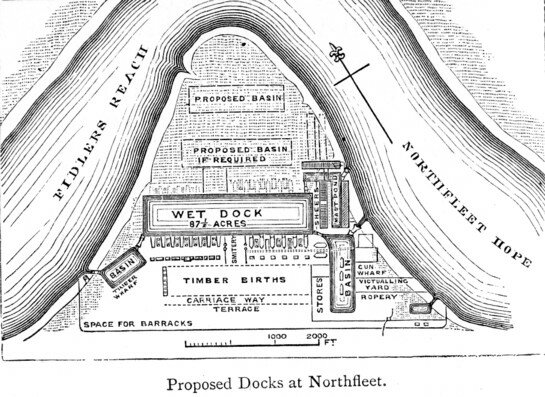

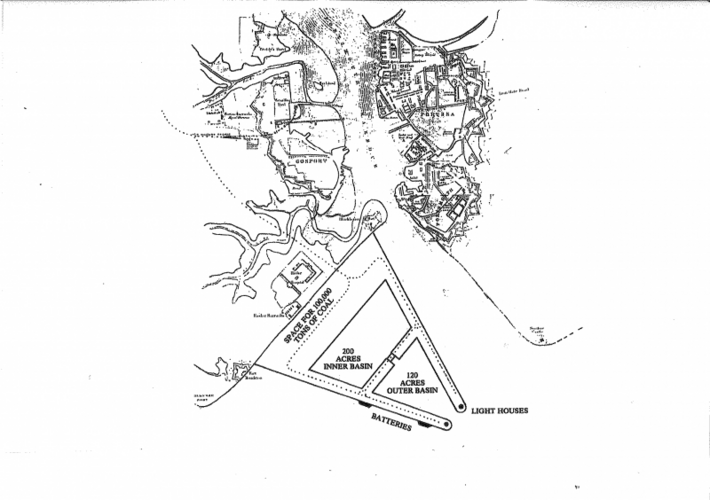

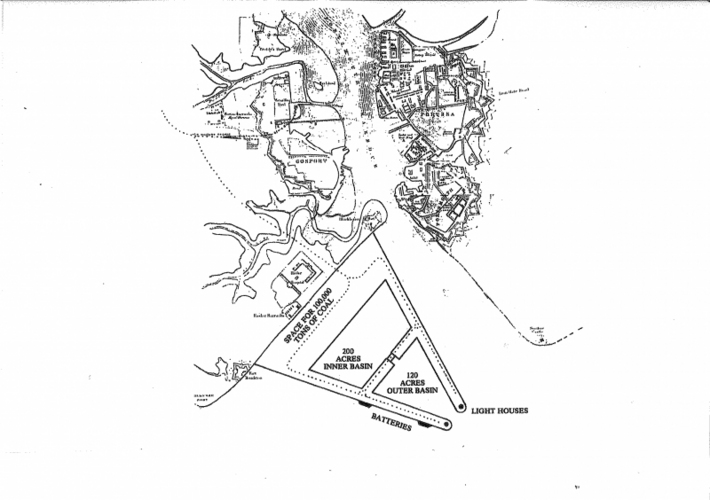

Perhaps the most startling of his observations concerned the dockyards of Woolwich and Deptford, both of which he recommended for closure. Too far up river, they suffered from a lack of space and were constantly subjected to silting and so could not be used effectively. Commenting on Woolwich, but later using a similar argument for Deptford, he informed the committee that ‘the enormous expense of removing the constant accumulation of mud in front of the dockyard and the confined and defective arrangement of the dockyard itself, were ample reasons for it being condemned as unfit for the construction and repair of great ships.’ To replace the two yards, Rennie suggested the founding of a new dockyard at Northfleet, down river but still on the Kentish side of the Thames and not far from Gravesend. With the purchase of sufficient land, it would prove an ideal site for a dockyard, designed at the very outset for building, constructing and refitted the largest of the nation’s warships. Included in the new Northfleet dockyard would be two large wet-docks, eight dry-docks and eight building docks:

'Ships will be launched immediately from these docks and slips into the great wet dock, without communicating with the river, and all vessels in ordinary may be moored on its north side, where there will be room enough to moor 70 sail of the line; or, if fewer ships of the line, a proportionate number of frigates and smaller vessels, without impeding or interfering with the works carrying out on the south side.'

In the event, the committee accepted the proposed scheme, recommending implementation in its entirety. The government went as far as acquiring the necessary land but unfortunately the pressures and expense of the war made the scheme impracticable and the project was cancelled with the return of peace.

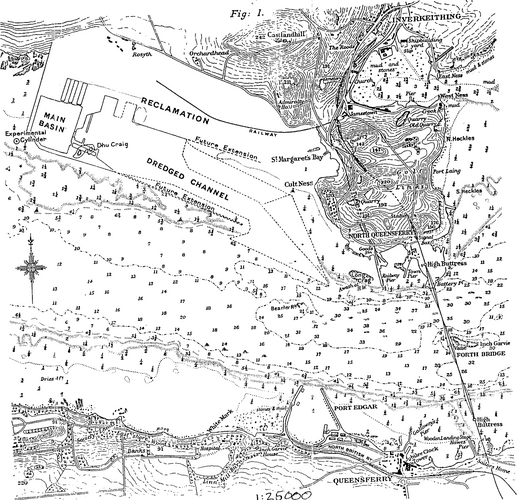

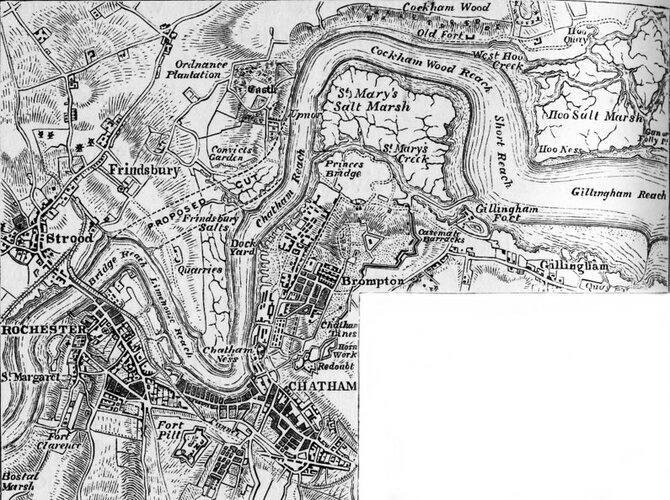

At Chatham, Rennie was just as radical in approach. Noting the restrictions of space and the shallow state of the Medway, he proposed the addition of massive wet docks formed out of the Chatham and Limehouse Reaches of the Medway. This would have provided considerable additional space for both dry-docks and slipways, whilst the entrance of the proposed wet-dock, being situated near Gillingham would go some way to alleviating the hazards of navigating the various twists and turns between Chatham and Sheerness. None of this, however, was constructed, again due to the expense involved.

John Rennie, as indicated was highly critical of dockyard design and layout. In examining each of the dockyards he ad suggested some very radical alternatives to the piecemeal improvement programmes that were usually adopted. He was aware, as were most critics that essentially the design of the six main yards had been determined during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. To impose upon this the needs of the nineteenth century was insane. Doubtless the Navy Board and the Admiralty were aware of this, but the necessary advances that Rennie indicated were beyond their limited finances. A confident wartime Admiralty promised itself new dockyards upon the return of peace, but with its arrival in 1815 government concern with the yards diminished. The sound proposals of John Rennie were quietly forgotten. Indeed, some thirty years later, when the Crimea was being fought and the ships themselves undergoing change, the dockyards remained unaltered. A chance to solve Britain’s shipbuilding and repair difficulties had, one again, been passed over.

No size of wet-docks, dry-docks or slips is given but I have read on line that the Northfleet proposal was to cover around 800 acres. ‘Royal Dockyards’ says the 1870’s extension to Portsmouth brought that yard to about 300 acres, the 1885 extension at Chatham added around 380 acres to the existing 97 acres and the 1890’s Keyham extension was about 246 acres though I have seen other figures quoted elsewhere.

Northfleet is opposite Tilbury, anyone know what the largest ship to get as far up the Thames as Tilbury is?

Royal Dockyards by Philip MacDougall Pages 134 – 136.

In the light of John Rennie’s great experience as an engineer, it is interesting to consider observations he made on various royal yards in 1807. These were prompted by a commission of enquiry that had been set up to examine defect in all naval establishments. Rennie was singularly unimpressed; he considered Plymouth to be the most suited, noting the spacious harbour, general lack of silting and the navigational hazards that would eventually be overcome by the breakwater. Portsmouth, on the other hand, was more heavily criticized for, at that stage, the harbour was showing definite signs of silting, whilst he considered the dockyard to lack adequate space for the various buildings and machine shops being built.

Perhaps the most startling of his observations concerned the dockyards of Woolwich and Deptford, both of which he recommended for closure. Too far up river, they suffered from a lack of space and were constantly subjected to silting and so could not be used effectively. Commenting on Woolwich, but later using a similar argument for Deptford, he informed the committee that ‘the enormous expense of removing the constant accumulation of mud in front of the dockyard and the confined and defective arrangement of the dockyard itself, were ample reasons for it being condemned as unfit for the construction and repair of great ships.’ To replace the two yards, Rennie suggested the founding of a new dockyard at Northfleet, down river but still on the Kentish side of the Thames and not far from Gravesend. With the purchase of sufficient land, it would prove an ideal site for a dockyard, designed at the very outset for building, constructing and refitted the largest of the nation’s warships. Included in the new Northfleet dockyard would be two large wet-docks, eight dry-docks and eight building docks:

'Ships will be launched immediately from these docks and slips into the great wet dock, without communicating with the river, and all vessels in ordinary may be moored on its north side, where there will be room enough to moor 70 sail of the line; or, if fewer ships of the line, a proportionate number of frigates and smaller vessels, without impeding or interfering with the works carrying out on the south side.'

In the event, the committee accepted the proposed scheme, recommending implementation in its entirety. The government went as far as acquiring the necessary land but unfortunately the pressures and expense of the war made the scheme impracticable and the project was cancelled with the return of peace.

At Chatham, Rennie was just as radical in approach. Noting the restrictions of space and the shallow state of the Medway, he proposed the addition of massive wet docks formed out of the Chatham and Limehouse Reaches of the Medway. This would have provided considerable additional space for both dry-docks and slipways, whilst the entrance of the proposed wet-dock, being situated near Gillingham would go some way to alleviating the hazards of navigating the various twists and turns between Chatham and Sheerness. None of this, however, was constructed, again due to the expense involved.

John Rennie, as indicated was highly critical of dockyard design and layout. In examining each of the dockyards he ad suggested some very radical alternatives to the piecemeal improvement programmes that were usually adopted. He was aware, as were most critics that essentially the design of the six main yards had been determined during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. To impose upon this the needs of the nineteenth century was insane. Doubtless the Navy Board and the Admiralty were aware of this, but the necessary advances that Rennie indicated were beyond their limited finances. A confident wartime Admiralty promised itself new dockyards upon the return of peace, but with its arrival in 1815 government concern with the yards diminished. The sound proposals of John Rennie were quietly forgotten. Indeed, some thirty years later, when the Crimea was being fought and the ships themselves undergoing change, the dockyards remained unaltered. A chance to solve Britain’s shipbuilding and repair difficulties had, one again, been passed over.

No size of wet-docks, dry-docks or slips is given but I have read on line that the Northfleet proposal was to cover around 800 acres. ‘Royal Dockyards’ says the 1870’s extension to Portsmouth brought that yard to about 300 acres, the 1885 extension at Chatham added around 380 acres to the existing 97 acres and the 1890’s Keyham extension was about 246 acres though I have seen other figures quoted elsewhere.

Northfleet is opposite Tilbury, anyone know what the largest ship to get as far up the Thames as Tilbury is?