Four generations of stealth preceded the design concepts for the first stealthy air-to-air fighters. To survive in the current air combat environment, the new designs combined stealth and high maneuverability with a long range supercruise capability. In addition to shape, these aircraft needed to prevent detection from radio transmissions, heat from the engines and other forms of energy detectable by specialized ground sensors.

The concept of an Advanced Tactical Fighter (ATF) dates back to 1971 during early studies of using stealth in the design of a modern fighter aircraft. Over the next decade, the U.S. Air Force’s Tactical Air Command (TAC) and other commands began to refine the requirements of the next generation of fighter aircraft. Despite limited and sporadic funding for these studies, most of the major aircraft manufacturers produced design concepts for the ATF.

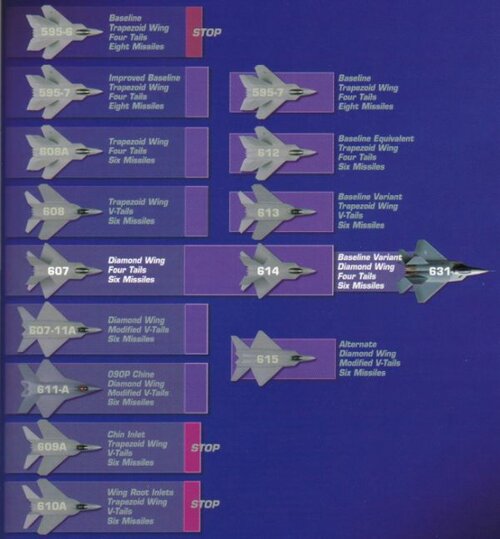

In mid-1981 the Air Force released a formal Request for Information (RFI) to the leading aircraft companies. With no government funding for these one-year studies, each company absorbed the cost. The RFI was sent to nine companies: Boeing, Fairchild Republic, North American Rockwell, General Dynamics, Lockheed, McDonnell Douglas, Grumman, Vought and Northrop. Of these nine, seven chose to participate, submitting a total of 19 concepts. Vought and Fairchild Republic chose not to participate.

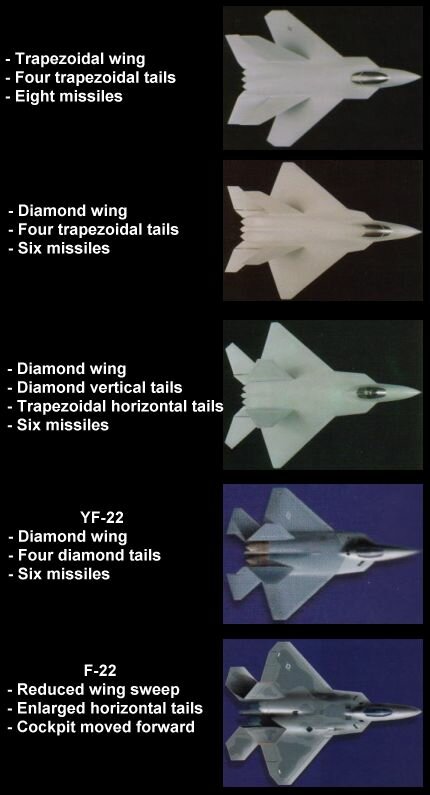

The 19 design concepts differed considerably in size, shape and maneuverability. As the studies progressed, the design parameters were refined from ‘Reduced RCS’ to ‘Low Observability’, to also include supercruise capability, advanced avionics and radar as well as high maneuverability. Concepts from each company incorporated some feature that would eventually be included in the design for the ATF. Winners of the competition were announced on October 31, 1986 with Lockheed and Northrop coming out on top. Instead of there being 5 losers, each prime contractor teamed with another member from the competition. Northrop teamed with McDonnell Douglas while Lockheed teamed with Boeing. The new aircraft received the designations of YF-22 for Lockheed’s design and YF-23 for Northrop’s.

Lockheed and Northrop used the prevailing years to refine their designs for the ATF so that by the time the selection was made, the ATF designs for each company evolved into a vehicle that closely matched those actually built. Along with airframe designs, two engine manufacturers were chosen to compete in the ATF competition. Pratt & Whitney entered with their YF-119-PW-100 design and General Electric went with the YF120-GE-100. One ATF prototype from each company would be powered using engines from each manufacturer. The first YF-22 and second YF-23 received the GE engines while the second YF-22 and first YF-23 received Pratt & Whitney powerplants.

Construction began almost immediately in order to meet the tight deadlines for the competition. Northrop was first to unveil their prototype in a rollout ceremony held at Edwards AFB on June 22, 1990. Northrop began engine runs the following month and the YF-23 moved under power for the first time on July 7. The YF-23 rapidly completed taxi testing with increasing speeds, culminating in the final high-speed test to 120 knots on August 11.

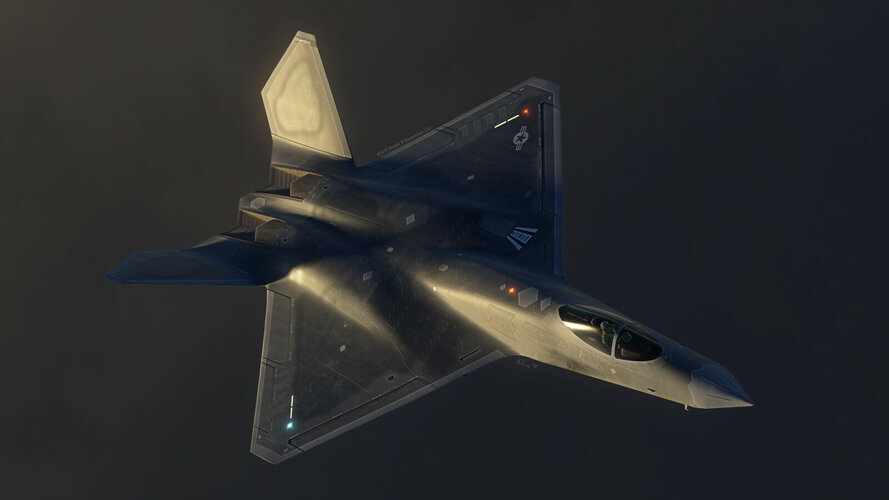

Unofficially dubbed ‘Black Widow II’, Northrop’s Prototype Air Vehicle (PAV) number 1 took to the air for the first time on August 27 making a near flawless one hour flight. Climb out was brisk, requiring the F-16 chase to use afterburner to stay with the YF-23 using military (non-afterburning) thrust. Northrop test pilot, Paul Metz, stated the aircraft was abnormally “solid” yet agile requiring few pilot stick motions to remain in tight formation with its safety chase aircraft. Lockheed unveiled their YF-22 prototype the following day in a ceremony held at Plant 10 in Palmdale, CA on August 28.

With the first flight completed, flight testing ramped up quickly. In order to maximize time aloft, the YF-23 qualified for air refueling on its fourth flight. Flying behind a KC-135 tanker, the YF-23 spent nearly three hours behind the tanker performing hookups and disconnects at various airspeeds and throughout the tanker’s boom envelope. Flight number 5 saw the YF-23 fly supersonic for the first time under the control of McDonnell Douglas’s test pilot, Bill Lowe. Afterwards the aircraft began testing supercruise speeds out to Mach number 1.5 and by flight number six, the first four YF-23 pilots received check out with the final pilot check coming with the program’s operational test pilot, Con Thueson, on flight number 11.

PAV-2 joined the flight program on October 26, 1990 with Jim Sandberg taking the GE powered aircraft on its first flight. Flights progressed rapidly with PAV-1 testing going well until October 30, when Bill Lowe experienced a shattered forward windscreen at Mach 1.5 during flight number 16. The glass outer layer of the windscreen cracked and the inner polycarbonate layer remained intact allowing for a safe landing. The same scenario repeated on PAV-2 nearly a month later.

Early flights in PAV-2 were troublesome. Its second flight was shortened when the left engine entered a sub-idle condition and would not accelerate and the plane made an uneventful single-engine landing. Flight number 3 on November 21 almost saw the end of PAV-2 when a plugged air sense line caused the fuel tanks to overpressurize. As the aircraft climbed in altitude, the internal pressures reached the structural limits of the fuel tanks. Quick action by the ground control room helped get the aircraft on the ground before serious damage to the airframe occurred. With these incidents behind them, PAV-2 settled in and became a reliable test aircraft. Both air vehicles now returned excellent performance data on the airframes, avionics and engines. The two prototype air vehicles flew together only once during the test program when Paul Metz in PAV-1 and Jim Sandberg in PAV-2 flew formation over the Mojave Desert on November 29. PAV-1 ended its flight testing career the following day with a six-flight surge and flutter test out to Mach 1.8, the highest speed attained by PAV-1. PAV-1’s flight test program lasted only 93 days.

With PAV-1 retired, all efforts were concentrated on expanding the supercruise envelope with PAV-2. The max supercruise speed with PAV-2 has never been publicly released, but it is stated to have been significantly faster than PAV-1. With funding running out, PAV-2 continued flight testing. On the next to last flight of PAV-2, a 15 minute formation with the first YF-22 occurred on December 18, this was the only time the two different prototypes flew together. The final flight of the program came during the second flight on December 18 when Ron ‘Taco’ Johnston took PAV-2 took up on a nearly 2 hour test mission. PAV-2’s flight testing lasted a mere 82 days.

Both aircraft were placed in flyable storage awaiting the decision on a winner of the ATF program. PAV-1 moved under power only three more times in January, February and March, 1991 during slow speed taxi runs to keep the aircraft in flyable condition.

The Air Force spent the first four months of 1991 evaluating the two airframe and engine proposals. On April 23, 1991, Secretary of the Air Force, Donald Rice announced that the Lockheed F-22 and Pratt & Whitney F119 won the competition for the ATF production contract. Secretary Rice’s announcement stated that both aircraft met the requirements for the ATF but the USAF had more confidence in Lockheed and Pratt & Whitney to ”manage” the program to deliver the weapons system on time and at cost.

After the ATF decision, both PAV’s, stripped of all government furnished equipment, including usable avionics & engines, were placed in outdoor storage in a small fenced area next to the B-2 test facility at Edwards AFB. After sitting in storage for nearly two years, ownership of both PAV’s was turned over to NASA on December 1, 1993. NASA Dryden Flight Research Center proposed doing structural testing of composite airframes but money was never found and both vehicles sat in outdoor storage in various locations around the center. 18 months after receiving the YF-23’s, NASA realized that no testing would be done and offered the airframes to museums. Ownership of PAV-1 transferred to the National Museum of the United States Air Force and the vehicle moved to the AFFTC Museum at Edwards AFB in May 1995 for temporary display. In August, PAV-2 was disassembled and transported to the Western Museum of Flight originally located in Hawthorne, CA but later moved to Torrance, CA. In 2000, PAV-1, disassembled and transported via C-5 Galaxy, went to the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio, where it is currently on display.