- Joined

- 27 December 2005

- Messages

- 17,753

- Reaction score

- 26,462

To counteract some bad/incomplete information on the F-15N "Sea Eagle" on the internet, here's a really good account from Dennis R. Jenkin's fine Aerofax on the F-15.

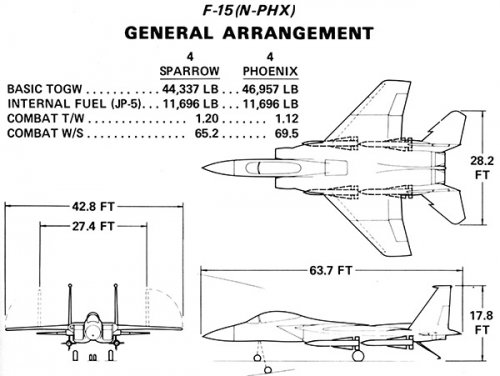

F-15(N) and F-15(N-PHX)

McAir spent considerable time and effort from 1970 to 1974 to define several versions of the F-15 for naval service. An unofficial (and perhaps, unwelcome) title of 'Seagle' was applied by various organizations involved. The first presentation to the Navy occurred in July 1971. McAir's position was that due to its excellent thrust-to-weight ratio and good visibility, the F- 15 could easily be adapted for carrier operations. The only modifications required to enable it to operate off of CVA-19 class (or larger) carriers were: strengthened landing gear; an extendible front landing gear strut to produce the proper angle of attack upon catapult launch; installation of a nose-tow catapult system; folding wings; and a beefed-up arresting hook and associated structure. Both the nose and main landing gear wells would have to be enlarged to accommodate the increased stroke of the new gear. These modifications would add approximately 2,300 pounds to the basic F-15A.

The Navy was not overly impressed with this proposal, so McAir further modified the design. Two McAir models (199-A-11 and 199-A-12) were then presented to the Navy. Model 199-A-12 featured a bridle catapult attachment, while 199-A-11 A had a nose-tow catapult attachment, otherwise they were identical. The design also featured a dual nose wheel arrangement, increased fuselage structural strength, a Navy-type refueling probe, and most important, an improved high-lift system, in addition to all the originally proposed modifications. The high-lift system was composed of full-span leading edge flaps, BLC trailing edge flaps, and a slotted aileron, all of which contributed 632 pounds to the projected 3,055 pound increase (to 42,824 pounds) over the USAF F-15A. An additional 71.9 pounds would be added for Navy avionics, including: AN/APN-15(V) radar beacon set; AN/ASW-27B digital data communications set; AN/ALQ-91A countermeasures set; AN/ASN-54(V) approach power compensator set; AN/ ALQ-100 deceptive countermeasures set; AN/ARA-63 receiver decoding group; and an AN/APN-194 radar altimeter. The standard TEWS ECM system would be deleted.

These versions of the F-15(N) were still armed the same as the USAF F-15A (M61A1, AIM-7, and AIM-9), and were deemed roughly equal to the F-14B in overall performance, except for range. The radius of action in a fighter-escort configuration was 271 nm on internal fuel, compared to 481 nm for the F-14B and 319 for the F-4J. With external tanks, this increased to 516 nm versus 685 for the F-14B and 485 for the F-4J. No data was generated for FAST Pack equipped aircraft. A total of $403.5 million was projected for non-recurring engineering costs, with a flyaway price of $7.6 million based on a 313 aircraft production run.

The F-15N then became the focus of Navy Fighter Study Group Ill. This group disregarded the McAir data, enlarged the nose to carry the AN/AWG-9 radar, and added Phoenix missiles, resulting in an aircraft that weighed 10,000 pounds more than the basic F-15A. This weight increase, along with the associated drag, greatly decreased the performance of the F-15, negating any advantage it had over the F- 14A. There was also considerable concern over the 12° angle-of-attack used by the F-15 (compared to 10.2° for the F-14A) during approaches, and the relatively narrow landing gear track.

McAir and Hughes countered the study group's criticisms with a further modified version known as F-15(N-PHX), which added a rudimentary AIM-54 Phoenix missile capability. This version (model 199-A-19B) took the model 199-A-11A and modified the AN/APG-63 radar set into an AN/APG-64. These modifications involved increasing the transmit power to 7 kW (compared to 10 kW in the AN/AWG-9 and 5.2 kW in the AN/APG-63), a command link, a track-while-scan capability, and a Phoenix test feature. The radar antenna was also modified to effect a slight frequency shift. The central computer had its load changed to support the new track-while-scan modes, as well as adding additional memory and Phoenix unique software. Some cockpit controls and displays were also modified. The aircraft could carry up to eight AIM-54s: one on each fuselage AIM-7 station, one on each inboard wing pylon, and two (in tandem) on a special centerline pylon. The appropriate missile cooling systems were added to each station. Take-off gross weight was up to 46,009 pounds. The high-lift devices were changed to include full-span Krueger leading edge flaps, BLC trailing edge flaps, and single-slotted ailerons. Approach speed to a carrier was estimated at 136 knots.

Another proposal was also presented, one essentially echoing the results of Navy Fighter Study Group Ill. The aircraft was equipped with the Hughes AN/AWG-9 weapons system from the F-14A, but otherwise resembled the earlier F-15(N-PHX). Estimated non-recurring R&D costs were $1.173 billion in FY72 dollars. Based on a313 unit production run, the flyaway cost was $11.5 million per aircraft.

On 30th March 1973, the Senate Armed Services Committee's ad hoc Tactical Air Power subcommittee started new discussions on the possibilities of modifying the F-15 for the Navy mission. At this point the F-14 program was having difficulties, and the subcommittee wanted to look at possible alternatives, namely lower-cost (stripped) F-14s, F-15Ns, and improved F-4s. There were even proposals by Senator Eagleton for a 'fly-off' between the F-14 and F-15, but this never transpired. These discussions, along with some other considerations, led to the forming of Navy Fighter Study Group IV, out of which the aircraft ultimately known as the F/A-18A was born.