Weapon systems and casualties

According to

Indian sources, Indian forces employed SCALP-EG land-attack cruise missiles and AASM HAMMER guided bombs during the strike. India likely operates the export variant of the SCALP-EG, which has a reduced range of approximately 250 kilometers. The HAMMER guided bombs have a maximum range of up to 70 kilometers, assuming release at optimal altitude and speed (i.e. high altitude/high velocity).

Following the attack,

images surfaced on social media showing the booster section and nose cap of a BrahMos PJ-10 cruise missile recovered on Indian territory. Both components are jettisoned shortly after launch, indicating that the missile was used in the operation. The BrahMos is a supersonic cruise missile based on the Russian 3M55 Oniks and was developed by the Indo-Russian joint venture BrahMos Aerospace, and has a range of 300-500 kilometers (depending on the variant).

However, rather than focusing on the targets struck and ammunitions used, much of the attention shifted to Indian losses. Shortly after the operation, Indian news outlets reported that Pakistan had shot down several Indian fighter jets involved in the strike. These reports were later deleted, likely following pressure from government officials—a pattern not unfamiliar in the context of past India-Pakistan military engagements.

That said, some Indian casualties have since been confirmed, and the available evidence does not reflect well on India’s performance.

Imagery of wreckage suggests that India lost at least one

Mirage 2000H, one MiG-29UPG or Su-30MKI (imagery

shows the K-36DM ejection seat, which is used in both aircraft, leaving the identification uncertain), and one Dassault Rafale F3R. Among these, only the downing of the Rafale has been officially acknowledged—confirmed by a high-ranking French intelligence official,

according to CNN.

Interestingly, all wreckage has been located inside Indian territory, in some cases as far as around 100 km behind the border, indicating that Indian aircraft likely did not attempt to penetrate Pakistani airspace, which aligns with the use of stand-off munitions.

To down the Indian multirole fighter jets, Pakistan reportedly used the PL-15E — a claim supported by recovered missile

debris and

components. The PL-15E is the export version of China’s PL-15 beyond-visual-range air-to-air missile (BVRAAM). It has a range of approximately 145 km, compared to the 200–300 km range of the domestic variant. The missile features a dual-pulse motor (providing burn-out speed in excess of Mach 5, then gradually slowing down), midcourse guidance via data link, and an active AESA radar seeker for terminal homing.

The PL-15E is integrated with Pakistan’s JF-17 Block III and J-10CE fighter aircraft. The J-10CE is equipped with a larger nose cone and a more powerful AESA radar, and can detect and track targets at distances exceeding the maximum range of the PL-15E. In contrast, the smaller AESA radar on the JF-17 Block III has a detection range of only 100–120 km, and is therefore unable to exploit the missile’s full range. Given that the downed Indian aircraft were located deep inside Indian territory, it stands to reason that J-10CE aircraft were used to launch the PL-15E missiles. However, this remains unconfirmed, and midcourse guidance could also have been provided by other assets — most notably Pakistan’s Saab 2000 Erieye AEW&C aircraft, of which it is known to operate nine.

Implications of the outcome

The engagement has several implications.

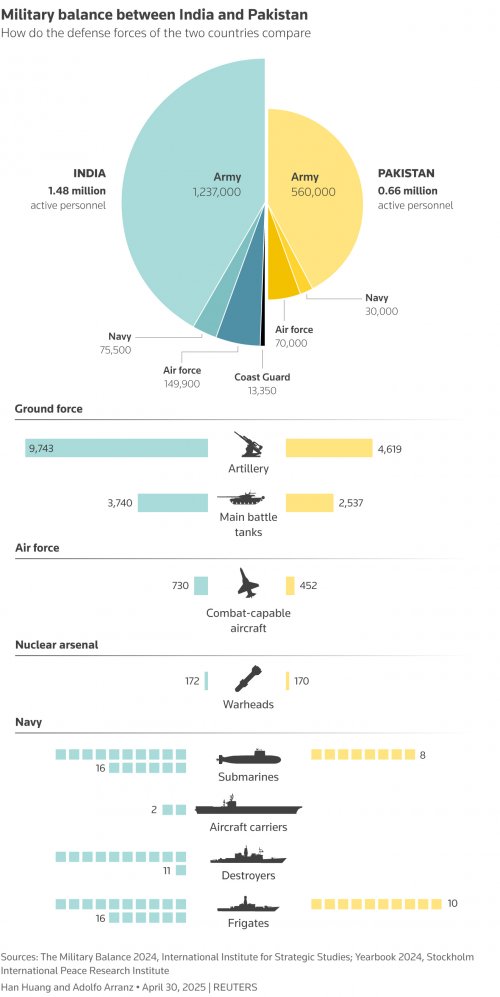

First, this was not a good day for the Indian Air Force. Historically, India has maintained a qualitative edge over Pakistan in the air domain. In recent years, however, as Pakistan has acquired more advanced Chinese platforms, observers have speculated that the technological gap may be closing. Last night’s events appear to lend weight to that assessment.

That said, force employment likely played a greater role than technology in the outcome. As noted, India appears to have relied exclusively on stand-off munitions during the strike, meaning its aircraft had no operational need to loiter in what turned out to be contested airspace. Instead of returning to their bases, they likely conducted defensive counter-air (DCA) missions, anticipating possible Pakistani retaliation. In doing so, however, Indian pilots clearly misjudged the engagement envelope of Pakistani fighter jets.

Second, and conversely, the episode reflects well on the Pakistani Air Force. Pakistan clearly anticipated the attack, positioned the appropriate countermeasures, and succeeded in downing multiple Indian aircraft. In doing so, it closed a fairly complex kill chain involving early warning, surveillance, target acquisition, tracking, and engagement. This is no small feat and suggests a degree of professionalism and technical capability.

That said, Pakistan was unable to fully prevent the strike and still suffered damage on its own territory. The success is therefore relative and only compared to previous engagements in which Indian aircraft operated in and around Pakistani airspace with fairly little consequence.

Third, the first confirmed combat loss of a modern Rafale fighter jet casts a shadow over Dassault’s recent momentum. In recent years, the Rafale has been the subject of overwhelmingly positive coverage, largely due to its export success and reputation as a high-performance multirole platform. This incident arguably introduces a setback to that narrative.

Importantly, this does not imply that the Rafale is a poor platform (the Eurofighter or the F-16 may have performed exactly the same). However, it does underscore its limitations as a fourth-generation aircraft, particularly in terms of survivability. While it remains unclear to what extent this incident was due to platform limitations versus operational error — the latter likely being the more decisive factor — it is reasonable to assume that Pakistani aircraft would have not been able to acquire and track a fifth-generation stealth platform like the F-35 at similar ranges, given its significantly lower radar cross-section.

Fourth, the air-to-air engagement casts Chinese aerospace technology in a favorable light. The Chinese-origin air-to-air missile, along with the platforms used to deliver it, appear to have performed effectively. This adds to the growing body of evidence that Chinese weapon systems must be taken seriously. While Russian technology has consistently underperformed in recent conflicts, there is no compelling reason to assume Chinese systems would fare similarly in a Taiwan contingency.

Fifth, and relatedly, there is likely something Western — and particularly American — military intelligence can take away from this engagement regarding Chinese technology. This marks the first confirmed operational use of the PL-15E, and, as noted, parts of the missile, including components of its AESA radar, have been recovered. U.S. military intelligence will likely find this material valuable and may be able to extract insights into Chinese missile design, guidance systems, and performance characteristics.