XP67_Moonbat said:

plus an Avweek article I've since lost

Found:

Aviation Week & Space Technology

March 13, 2000

747 Studied In Launch Role

BYLINE: BRUCE A. SMITH

SECTION: WORLD NEWS & ANALYSIS; Vol. 152, No. 11; Pg. 33

DATELINE: LOS ANGELES

Boeing is wind-tunnel testing a large booster that would be deployed from the top of a modified 747-400F for a launch-on-demand capability.

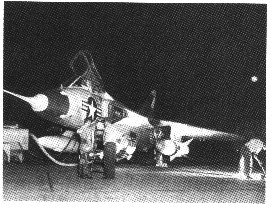

The design, called AirLaunch, is similar in concept to Orbital Sciences Corp.'s Pegasus XL in its use of a wide-body transport to serve as the ''first stage'' of the launch system. Pegasus is carried under the fuselage of an L-1011.

AirLaunch has been designed as a possible booster for the U.S. Air Force's proposed space maneuver vehicle (SMV), an unpiloted, reusable spacecraft intended to support various military space activities ranging from satellite deployment to on-orbit operations.

The AirLaunch system -- for missions to low-Earth orbit (LEO) and lower medium-altitude orbits -- would be developed in two primary configurations. The first would be to place an SMV in orbit in support of military operations, while the second would be an expendable Conventional Payload Module (CPM) for civil, commercial and military missions. The booster could lift a 7,500-lb. payload to low-Earth orbit.

''The principal driver for the airborne launch system is launch-on-demand,'' according to Rick Stephens, vice president and general manager of Boeing Reusable Space Systems.

STEPHENS SAID BOEING SEES A MARKET requirement primarily driven by the government or military segment, but added that the company's market analysis indicates there are commercial customers who are also looking at launch-on-demand capability.

Boeing plans to conduct a system-requirements review for AirLaunch in June or early July, followed by a preliminary design review in November. A decision on whether to proceed with development could be made late this year.

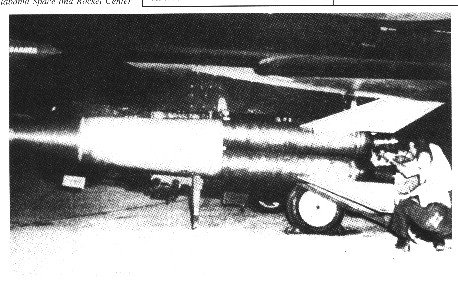

The Boeing booster, significantly larger than Pegasus XL, is carried on top of the aircraft because of its larger size. The first two AirLaunch stages would be Thiokol Castor 120 solid rocket motors, derivatives of MX ICBM motor designs used on Lockheed Martin's Athena 2 launcher.

The first and second stages alone are about 60 ft. long when stacked, with a diameter of 7.7 ft. The third-stage motor would be a proprietary design which is being developed by Thiokol, a planned strategic partner in the program. Officials said payload performance would be just under that of the Boeing Delta II booster.

''We really see it as a complement to the other Boeing launch systems,'' Stephens said. ''It does bump up against Delta II, but it does not have the capability to replace Delta II.''

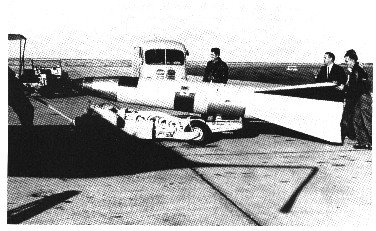

AirLaunch would be carried to an altitude of 18,000-30,000 ft. by the 747 freighter aircraft where it would separate at a velocity of Mach 0.7-0.75. Equipped with wings and a tail section, the booster would glide for 30-40 sec. to achieve a 4-5-mi. separation from the aircraft prior to first-stage motor ignition. The booster would lose 2,000-3,000-ft. in altitude during the glide phase, program officials estimated.

The wing would not have control surfaces, but empennage control surfaces would provide pitch and yaw inputs during the short glide phase and for the start of first-stage motor firing. Within 5 sec. of ignition, the wings and tail assembly would be jettisoned at a velocity of about Mach 0.92.

Program officials said they have some data which can be used for the program as a result of Rockwell's experience in the mid-1970s on the space shuttle program. During testing in 1977, the space shuttle Enterprise was deployed from NASA's 747 shuttle carrier aircraft for approach and landing tests at Edwards AFB, Calif.

THE ROCKWELL ORGANIZATION, which built the shuttle orbiter fleet and was involved in the landing tests at Edwards, was acquired by Boeing in 1996.

The AirLaunch system would have a launch weight of about 300,000 lb. The 747 would be modified during production for additional structural strength, as well as to install the booster attach points on the fuselage.

Launch-on-demand would enable tactical responses to support sortie and free-flier satellite missions. Some roles envisioned for the system include replenishment of LEO satellites, remote sensing, hypersonic research and technology development.