Just a nice image of Vertical Aerospace's VX4

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

VTOL On Demand Mobility

- Thread starter Grey Havoc

- Start date

eVTOLs: A New Bubble?

(Source: special to Defense-Aerospace.com; posted June 08, 2022)

By Tim Maxwell

PARIS --- Over the last ten years, the development of an Urban Air Mobility landscape has become an important trend in the air transportation industry. Unlike the jetliner market, historically oligopolistic (or even duopolistic), these small electric aircraft are at the center of a fierce battle involving hundreds of new players, themselves often with adjacent partners in industries like automotive, 3D printing, innovative batteries, completion centers and others.

In spite of this considerable fragmentation, money from investors has been flowing into the industry. According to McKinsey analysts, as of the end of February 2022, the eVTOL industry had benefitted from a total known equity funding of $12.8bn since 2010. The reasons for this hype are multifold. In a report issued in 2018, the consultancy Roland Berger argued that “as urban sprawl increases and road traffic congestion worsens, several distinct technological advances are putting the long-held dream of escaping from all this madness and taking to the air within our reach.” Said innovations have achieved varying levels of maturity so far, and notably include electric propulsion, autonomous flight technology and the implementation of 5G communication networks.

What is more compelling for investors than technological prowess, though, is to look for a not-too-risky cash cow and bet big bucks on it. EVTOLs, like many technological innovations before them, are benefitting from a strong support from state institutions: in 2019, the White House included eVTOLs into its R&D budget priorities. Then, in November 2021, the US House of Representatives passed the Advanced Air Mobility Coordination and Leadership Act, aiming to “coordinate efforts related to the safety, infrastructure, physical security, cybersecurity and federal investment necessary to bolster the AAM ecosystem, particularly passenger-carrying aircraft, in the United States.”

It is difficult to know for sure how much government money was injected into this flourishing industry to date, but reports indicated that as of March 2021, the US federal government had invested more than $130mn —a figure which does not include early investments in infrastructure. So, are eVTOLs the new cash cow? Maybe. Only in this case, they could well turn out to be fool’s gold for investors.

Misleading investment forecasts?

Whilst analyses focusing on the eVTOL industry blossom, there is no single figure generally agreed on as to the size this market is likely to reach. UAM enthusiasts generally tend to think that Urban Air mobility will be a trillion-dollar business by 20 or 30 years’ time. According to Morgan Stanley, the global eVTOL market could be worth $1 Trillion in 2040 (a figured concurred by Nexa Capital Partners)… and $2.3Trillion to $18.9 Trillion by 2050.

Quite a wide discrepancy! Other analysts, less forward-looking, are somewhat less bullish: the Indian firm Fortune Business Insights for instance anticipates a $23.2 billion global market by 2028. Morgan Stanley’s estimate for 2040 also contrasts with the Aerospace Industries Association’s, which sees the market reaching $325 billion by then.

In 2018, Porsche Consulting was estimating the worldwide vertical electric market worth $74 billion by 2035, of which passengers only traffic (intra-city or city-to-city) would represent $32 billion. For its part, BIS research, anticipates the global eVTOL market to be worth approximately $524million by 2025 and is projected to reach $1.9 billion by 2035, a much more careful projection to say the least. The truth is, making assumptions beyond, say, a 10-year horizon is quite risky, if not misleading.

Lessons from the VLJ air taxi bubble.

For some observers, the excitement surrounding eVTOL probably recalls the fuss about very light jet air taxis in the 2000s. Numerous models were competing to get their fair share of the money going into such projects, promoted by many brand-new operators. Bill Gates notoriously invested in Eclipse Aviation; the car manufacturer Honda launched the Honda Aircraft Company to produce its HondaJet; and smaller, ambitious players like Adam Aircraft boasted their advance compared to their rivals.

By 2009, Eclipse and Adam Aircraft had gone bankrupt, like many of their competitors; Honda only got its jet certified in 2015 (though it proved to be a success since then). Cessna’s Citation Mustang and Embraer’s Phenom were pretty much the only ones to firmly stay in business after this hype.

Sure, the financial crisis played a part in these multiple failures. But some elements are quite familiar to the challenges faced by the eVTOL industry, not least air traffic management issues, the long path to certification. Let’s also mention the risks associated with an over-reliance on non-binding orders coming in the form of a letter of intent or memorandum of understanding. The eVTOL industry as a whole has just reportedly passed the 5.000 “orders and commitments” threshold, including 4700 just over the last twelve months. We’d be happy to know the break-up between firm and conditional orders, as well as amount of the deposits actually paid so far…Those order intents are certainly made in good faith, but what will happen in case technical failures – God forbid – claim casualties? Finally, the UAM business model is not immune to exogenous risks and economic shocks, such as inflation, raw materials shortages, or even a future financial crisis… EVTOLs may well be protected from variations in oil prices, but a significant hike production and operating costs would be enough to jeopardize the promises of eVTOL journeys affordable for the many.

The road to certification, an uphill battle

eVTOL players are generally optimistic about the timeline leading to the entry into service of those new air taxis. The numerous provisional orders surely give reasons for optimism, with Embraer’s Eve having recorded orders for 1,785 units to date, and Vertical Aerospace for 1,350 units, by way of illustration. Another reason for optimism came from the European Aviation Safety Agency itself, estimating that the first eVTOL commercial services could start in 2025 at the latest.

In the US, Joby Aviation recently got its first certificate for commercialization from the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) —though a Type Certificate as well a Production Certificate are yet to be obtained. Another illustration for this optimism: In view of the 2024 Olympics, the Paris Transportation Administration plans to fly the first air taxis in the sky of the French capital.

But such a tight calendar will obviously cause tradeoffs, probably scrapping off much of the promises made by eVTOL promoters. First, while eVTOLs have been marketed as way less noisy than helicopters, their inability to fly at high altitudes means the cruel laws of physics may well be an obstacle. As argued by Bloomberg’s David Fickling, “Noise corresponds a lot to distance, making an eVTOL quieter the higher its cruising altitude. But climb higher, and you’re using more fuel again. It’s almost impossible to be energy-efficient and noise-efficient at the same time.”

Should certifying authorities augment the current threshold in aircraft noise regulations, this would inevitably create problems of public acceptance as a result. Second, and this is another consequence of eVTOLs’ low flying altitudes, air taxis will often be caught in tough weather conditions. An eVTOL ride will not be a smooth ride, as the clean lines of their designs and the blue skies of the promotional videos would have you believe.

Third (last but not least), it is clear that the first air taxis will not be autonomous. With one or two pilots onboard, the aircraft operating cost will inevitably go up, in turn casting doubt on the business case for eVTOLs, largely based on the extra room for passengers or cargo enabled by autonomy. This further brings the question of pilot certification: it is unclear for now under which category or type rating will they need to be certified to fly these aircraft.

Even having a single pilot onboard is a major change for regulating authorities, as much of the functions usually fulfilled by the co-pilot would now be part of the embedded autonomous systems. More generally, the FAA has stated that its current regulations are not tailored for power-lifted vehicles “which take off in helicopter mode, transition into airplane mode for flying, and then transition back to helicopter mode for landing.”

Inherent safety concerns.

Obviously, full autonomy as well as the use of embedded autonomous systems in complement to a single pilot raise significant safety interrogations, especially for aircraft meant to fly above densely populated areas. Although manufacturers and regulation authorities alike are showing a great commitment to ensuring high safety standards, statistics hardly lie. While commercial jetliners must comply with standards of one failure per million flight hours (10-6 reliability), the EASA is requiring a 10-8 reliability for “catastrophic failures” on eVTOLs with 2 to 6 passengers. With 100,000 passenger drones operating worldwide (as Roland Berger envisions by 2050), each flying 3,000 hours per year (a scale envisioned by many eVTOL proponents), it would still equate to three catastrophic failures a year…

Although this would result in less casualties than commercial jetliners overall, it is unsure whether such a rate of accidents could be accepted by the public in urban areas. More hypothetically but also more worryingly, eVTOLs could be targets of malicious acts, be it from hijackers or cyber attackers, given the numerous electronics embedded and high degree of connectivity of such aircraft.

Ground infrastructure will not develop overnight

The last source of uncertainty is the great challenge of developing a proper ground infrastructure. Obviously, with airport shuttling being likely to be the main use for the first eVTOLs in service, airports are already reflecting upon the adaptations they should bring to their existing infrastructure in order to host fleets of air taxis. Using helipads is another possibility. This will not be sufficient, however, for eVTOL manufacturers to be able to follow their business plans. The common image of air taxis landing on rooftops is yet another illusion for the short and mid-term, considering the safety and logistics issue it would actually bring.

Therefore, developing so-called “vertiports” will be instrumental to the success of urban air mobility. Their development, however, will not start before eVTOLs get final certification from regulating authorities, as acting otherwise would be foolishly risky for investors. Even once these efforts could get kick-started, it will take a lot of efforts —and money— to get the land and clearances to build such infrastructures within (or close to) densely populated areas. As explained by Charles Alcock, Senior Editor at Aviation International News, the perfect vertiports site would need an unobstructed airspace, a large square footage, no zoning limitations, and favorable local wind patterns... Not a piece of cake!

Lastly, the greater challenge to achieving the establishment of the necessary infrastructure perhaps lies in the air traffic management of skies filled with thousands eVTOLs at any given moment. During a recent webinar, Volocopter’s new CEO and former Airbus Defense & Space Chief executive Dirk Hoke emphasized that point, saying future air traffic management systems will need to include a great deal of digitalization, in order to support humans who would otherwise quickly be overwhelmed. Such changes in air traffic management systems will take years to unfold and mature.

EVTOLs may or may not end up crowding our skies, due uncertain public acceptance and other potential adverse circumstances. What seems clear, however, is that such uncertainty should discourage anyone a) willing to cash out quickly, and b) slightly concerned about technological ventures ending up in bubbles (like VLJ air taxis).

In spite of an intense engineering and marketing activity worldwide, the age of the Electric Air Taxi for all has not yet begun...

-ends-

alberchico

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 14 January 2014

- Messages

- 707

- Reaction score

- 1,513

Autoflight releases full-length eVTOL flight test video

Shanghai-based eVTOL company Autoflight has been ploughing through flight tests of late as it continues to develop its Prosperity I eVTOL air taxi. The company has now released a largely uncut 8-minute video showing an entire test flight, with sound.

alberchico

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 14 January 2014

- Messages

- 707

- Reaction score

- 1,513

Joby bought hydrogen pioneer H2Fly in secret

Secret acquisition of H2Fly signals bigger ambitions for the eVTOL startup. Revelation comes a day after The Air Current profiled H2Fly.

theaircurrent.com

theaircurrent.com

This was unexpected. So it looks like Joby is not 100 % sure of the long term prospects regarding how much battery density can be improved and they are dipping their toe into hydrogen in order to have a backup. Realistically any future large Evtol with a payload and range similar to a comparable helicopter would require either hybrid or hydrogen propulsion. Batteries just wont cut it.

Interestingly there is a startup developing a hydrogen powered Evtol but as of 2021 they were still looking for investors in order to move ahead with their project so it's currently in limbo.

Skai revises targets for its liquid-hydrogen, long-range eVTOL

East Coast aviation company Alakai made big headlines last year when it became the first eVTOL air taxi company to put hydrogen on the table as a way to get around the battery bottleneck that's holding so many competitors down to short flight times with long charging waits in between.

Last edited:

Charlesferdinand

amateur theologian

- Joined

- 24 October 2013

- Messages

- 172

- Reaction score

- 274

An E-VTOL start up that can't find investors? I didn't know such a thing was even possible.Interestingly there is a startup developing a hydrogen powered Evtol but as of 2021 they were still looking for investors in order to move ahead with their project so it's currently in limbo.

- Joined

- 27 May 2008

- Messages

- 1,179

- Reaction score

- 2,485

An E-VTOL start up that can't find investors? I didn't know such a thing was even possible.

3 points;-

1- All investors are not created equal. Most eVTOL start up’s have taken easy money from high risk takers, with low understanding of the technology (foolish) and are lower net worth who could never afford the whole development

2- News is spreading among new entrance low tier investors, of the above taking big losses .

3- US interest rates are rising = global recession on its way for 2023.

The times they are a’changing.

Last edited:

alberchico

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 14 January 2014

- Messages

- 707

- Reaction score

- 1,513

Air taxi certification times could be unrealistic: US government report

A US government report suggests certification of electric air taxis could take longer than some manufacturers are promising, citing formidable hurdles yet to be overcome.

People in the industry have known this all along.

I suspect the first real roles for these sorts of vehicles won't be the 'jetsons' style 'flying Ubers' that many show in images etc. I still believe there are roles for them though and the technologies involved will find use. I wouldn't be surprised to see some adopted in military roles.

alberchico

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 14 January 2014

- Messages

- 707

- Reaction score

- 1,513

I suspect the first real roles for these sorts of vehicles won't be the 'jetsons' style 'flying Ubers' that many show in images etc. I still believe there are roles for them though and the technologies involved will find use. I wouldn't be surprised to see some adopted in military roles.

I agree, I think that carrying cargo would be the ideal way to put these things to test under real world conditions, it satisfies regulators and dosen't put any passengers in harms way.

- Joined

- 24 November 2008

- Messages

- 1,549

- Reaction score

- 2,612

That's exactly what Pipistrel is planning to do...I suspect the first real roles for these sorts of vehicles won't be the 'jetsons' style 'flying Ubers' that many show in images etc. I still believe there are roles for them though and the technologies involved will find use. I wouldn't be surprised to see some adopted in military roles.

I agree, I think that carrying cargo would be the ideal way to put these things to test under real world conditions, it satisfies regulators and dosen't put any passengers in harms way.

https://www.pipistrel-aircraft.com/aircraft/nuuva-v300/

Attachments

Last edited:

alberchico

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 14 January 2014

- Messages

- 707

- Reaction score

- 1,513

alberchico

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 14 January 2014

- Messages

- 707

- Reaction score

- 1,513

A look at Zenlabs’ eVTOL battery technology that caught Lilium’s attention

We spoke to Michael Sinkula from Zenlabs, who gave us his candid view on the state of play and future for eVTOL battery technology.

A surprisingly detailed interview regarding the batteries that Lilium plans to use. Also, they are planning to modify the design to permit utilize rolling landings to reduce battery consumption.

Lilium highlights eVTOL design changes, introduces short running landing capability

With plans to build its first conforming eVTOL aircraft next year, German startup Lilium highlighted to shareholders changes to its aircraft design, including a new short running landing capability.

- Joined

- 24 November 2008

- Messages

- 1,549

- Reaction score

- 2,612

A look at Zenlabs’ eVTOL battery technology that caught Lilium’s attention

We spoke to Michael Sinkula from Zenlabs, who gave us his candid view on the state of play and future for eVTOL battery technology.evtol.com

A surprisingly detailed interview regarding the batteries that Lilium plans to use. Also, they are planning to modify the design to permit utilize rolling landings to reduce battery consumption.

Interesting article...

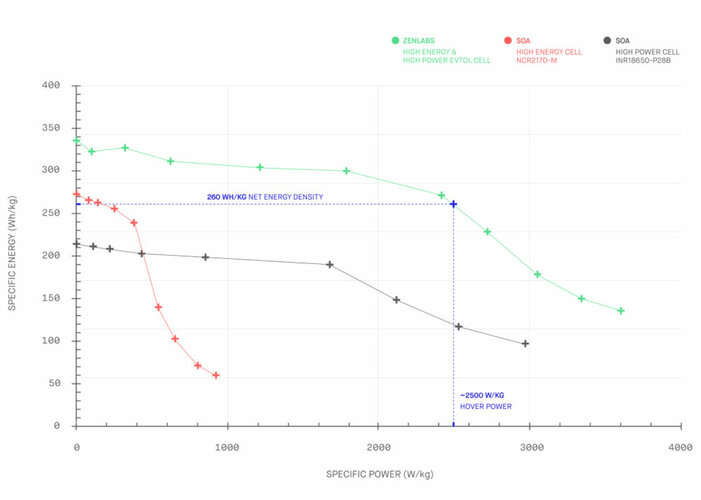

So, Zenlabs (Lilium's) energy density is 330 Wh/kg (max) at cell level, which does not include the containment box, the battery management system, any cooling system, etc.

alberchico

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 14 January 2014

- Messages

- 707

- Reaction score

- 1,513

The daunting economics of taking an air taxi to work

Why commuting isn't such a great use case for eVTOLs.

theaircurrent.com

theaircurrent.com

This article has a hard paywall, but I believe this is the report that it references:

This industry seems to have the same rosy projections that the aviation industry had during the very light jet craze of the early 2000's. Projections that did not stand up under close scrutiny. I think the biggest mistake these upstart companies are making is that they are grossly underestimating the operating costs of these advanced aircraft, as well as assuming that all the infrastructure and skilled workers to support such a massive fleet of evtols will be available by the time they enter service. To make things worse, economists are predicting a major recession for 2023. For those who don't remember, the 2008 recession is what burst the VLJ bubble.

This old article from 2008 talks about the collapse of a prominent air taxi operator that was using a fleet of VLJ's in what was essentially the beginning of the end for a new type of aircraft that was supposedly going to revolutionize the aviation industry:

Sun Sets on DayJet—More wreckage along the VLJ highway

What started as a bad week for Wall Street has ended as an even worse week for DayJet and possibly for VLJ manufacturers counting upon a robust per-seat, on-demand air taxi business. DayJet’s website says that it “has discontinued its...

www.maxtrescott.com

Last edited:

alberchico

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 14 January 2014

- Messages

- 707

- Reaction score

- 1,513

alberchico

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 14 January 2014

- Messages

- 707

- Reaction score

- 1,513

The FAA makes a U-turn on its approach to powered-lift, as the eVTOL industry tries to hang on

The Vertical Flight Society’s Mike Hirschberg shares his take on the FAA’s recent decision to change course on eVTOL certification.

An interesting article that predicts trouble if the FAA drags their feet in adopting the new certification rules for these new aircraft. There's also the possibility that some of these srart ups could run out of funding and go bankrupt if they can't get their designs certified in a timely manner.

To rephrase my earlier post (moderated), Safety is paramount in this industry. You can't geopardize any ounce of it for profit.

This was historically the way aviation lifted itself up to what it is today. There is no going back or any profitable alternative.

This was historically the way aviation lifted itself up to what it is today. There is no going back or any profitable alternative.

alberchico

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 14 January 2014

- Messages

- 707

- Reaction score

- 1,513

Inter-city eVTOL transport “marginal at best” - French Air and Space Academy - Urban Air Mobility News

“Prospects for inter-city transport by e-VTOL are considered marginal at present because of their limited range (less than 100 km today) and market (too small

www.urbanairmobilitynews.com

www.urbanairmobilitynews.com

I have been trying really hard to root for this industry, but there are too many red flags around the viability of this whole concept.

Vertical Aerospace and Molicel partner to power the VX4 eVTOL - Aerospace Manufacturing

eVTOL company Vertical Aerospace has signed a strategic partnership with E-One Moli Energy Corp (Molicel), a leading manufacturer of lithium-ion cells, to supply high power cylindrical cells for Vertical’s VX4 aircraft.

alberchico

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 14 January 2014

- Messages

- 707

- Reaction score

- 1,513

View: https://mobile.twitter.com/ArcherAviation/status/1547614279355883520

At least this company shares regular updates on how flight tests of its prototype are progressing.

At least this company shares regular updates on how flight tests of its prototype are progressing.

alberchico

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 14 January 2014

- Messages

- 707

- Reaction score

- 1,513

Hyundai Motor Group and Rolls-Royce team up to help electrify the future of air mobility

Hyundai Motor Group and Rolls-Royce Holdings have announced the mutual signing of a Memorandum of Understanding to work together to integrate all-electric propulsion into the Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) market. The parties look to combine Rolls-Royce’s expertise in aviation with Hyundai’s BEV...

shin_getter

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 1 June 2019

- Messages

- 1,109

- Reaction score

- 1,486

Drone Airspace: A New Global Asset Class

There’s still time to protect competition and innovation in drone services and technology

Drone Airspace: A New Global Asset Class

Drone airspace resembles spectrum in the 1980s, an appreciating asset that could be bought, subleased, traded, and borrowed against – if it were only permitted.

Much like legacy spectrum policy, there is immense technocratic inertia towards rationing airspace use to a few lucky drone companies. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has begun drafting long-distance drone rules for services like home delivery, business-to-business delivery, and surveying. In the next decade, drone services companies will deploy mass-market parcel delivery and medical deliveries in urban and suburban areas to make deliveries and logistics faster, cheaper, and greener.

…Federal officials recognize that the current centralized system of air traffic management won’t work for drones: at peak times today, US air traffic controllers actively manage only about 5,400 en route aircraft.

Red flags abound, however. FAA’s current plans for drone traffic management, while vague and preliminary, are clear about what happens once local congestion occurs: the agency will step in to ration airspace and routes how it sees fit. Further, the agency says it will closely oversee the development of airspace management technologies. This is a recipe for technology lock-in and intractable regulatory battles.

US aviation history offers the alarming precedent of expert planning for a new industry. In 1930 President Hoover’s Postmaster General, who regulated airmail routes, and a handpicked group of business executives teamed up to “rationalize” the nascent airline marketplace. In private meetings, they eliminated the established practice of competitive bidding for air routes, divided routes amongst themselves, and reduced the number of startup airlines from around forty to three.

“Universal” and “interoperable” air traffic management are popular concepts in the drone industry, but these principles have destroyed innovation and efficiency in traditional airspace management. The costly US air traffic management system still relies on voice communications and manual writing and passing of paper slips. Large, legacy users and vendors dominate upgrade efforts, and “update by consensus” means the injection of innumerable veto points. Drone traffic management will be “clean sheet,” but interoperable systems are incredibly difficult to build and, once built, to upgrade with new technology and processes. More than 16,000 FAA employees worked on the over-budget, pared-down, years-delayed air traffic management upgrades for traditional aviation.

…To avoid anticompetitive “route-squatting” and sclerotic bureaucratic control of a new industry, aviation regulators should announce a national policy of “airspace markets” – government sales of high-demand drone routes, resembling present-day government spectrum auctions.

alberchico

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 14 January 2014

- Messages

- 707

- Reaction score

- 1,513

View: https://mobile.twitter.com/jobyaviation/status/1550139901311688704

Finally the first production aircraft comes together.

Finally the first production aircraft comes together.

- Joined

- 24 November 2008

- Messages

- 1,549

- Reaction score

- 2,612

Here we go. Volkswagen is in the game as well

View: https://twitter.com/chineseflyer/status/1552249296984182785?t=o02uej5Npx0lwWEVHNjABg&s=19

View: https://twitter.com/chineseflyer/status/1552249296984182785?t=o02uej5Npx0lwWEVHNjABg&s=19

Attachments

Notice that this is purely a VTOL without much allowance for cross winds (skids and small rotor disks). You have to wonder why they don't simply put a more traditional rotor on top and call it an helo with a plug...

shin_getter

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 1 June 2019

- Messages

- 1,109

- Reaction score

- 1,486

alberchico

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 14 January 2014

- Messages

- 707

- Reaction score

- 1,513

View: https://mobile.twitter.com/elanhead/status/1554848825856122885

theaircurrent.com

theaircurrent.com

"Exactly what regulators will require is still being defined. Their starting point is DO-311A, the standard that was developed in the wake of the lithium-ion battery incidents that grounded the Boeing 787 back in 2013"

Considering that many of these eVTOL designs have a limited range and payload to begin with, any regulatory requirements that adds excessive weight to the aircraft might make them commercially nonviable. This could ultimately be what kills off a lot of these projects. But then again, regulators are 100% right to lean on the side of caution regarding battery safety requirements, especially when it comes to preventing thermal runaway events.

Batteries are a looming certification challenge for electric aviation hopefuls

Emerging safety requirements for lithium propulsion batteries put a focus on eVTOL weight and performance

theaircurrent.com

theaircurrent.com

"Exactly what regulators will require is still being defined. Their starting point is DO-311A, the standard that was developed in the wake of the lithium-ion battery incidents that grounded the Boeing 787 back in 2013"

Considering that many of these eVTOL designs have a limited range and payload to begin with, any regulatory requirements that adds excessive weight to the aircraft might make them commercially nonviable. This could ultimately be what kills off a lot of these projects. But then again, regulators are 100% right to lean on the side of caution regarding battery safety requirements, especially when it comes to preventing thermal runaway events.

The solution is easy in the context of urban mobility: cap barometric height to less than 5k ft and you should have simplified thermal runaway problems to that of the cooling aspect (something that should already be in place).

Airliners do climb to much higher heights that have no relevance to e-vstol, at least for a couple of decades...

Airliners do climb to much higher heights that have no relevance to e-vstol, at least for a couple of decades...

alberchico

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 14 January 2014

- Messages

- 707

- Reaction score

- 1,513

Up, up and ‘oh no’: The trouble with air taxi startups

Despite the many mishaps, the FAA says it's still on track to certify a number of the aircraft for carrying passengers by 2024.

Here is the GAO report the article references:

Transforming Aviation: Stakeholders Identified Issues to Address for 'Advanced Air Mobility'

In the near future, "Advanced Air Mobility" services could fill the skies with small, highly-automated, electric aircraft that can take off and land...

A lot of the issues there are not unique to the eVTOL arena

Up, up and ‘oh no’: The trouble with air taxi startups

Despite the many mishaps, the FAA says it's still on track to certify a number of the aircraft for carrying passengers by 2024.www.seattletimes.com

Here is the GAO report the article references:

Transforming Aviation: Stakeholders Identified Issues to Address for 'Advanced Air Mobility'

In the near future, "Advanced Air Mobility" services could fill the skies with small, highly-automated, electric aircraft that can take off and land...www.gao.gov

alberchico

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 14 January 2014

- Messages

- 707

- Reaction score

- 1,513

View: https://mobile.twitter.com/ArcherAviation/status/1557343943792111616

Some big news for Archer and their eVOL project.

Some big news for Archer and their eVOL project.

- Joined

- 18 October 2006

- Messages

- 4,211

- Reaction score

- 4,920

I have no doubt that our most progressive of bureaucratic agencies, the FAA, will work diligently to assist in making logical decisions on moving toward flight worth technology. Just like they have done with civil tilt rotor technology.

I imagine thet are quite excited at the prospect of having thousands of small air vehicles buzzing around at low altitude between skyscrapers in large cities.

I imagine thet are quite excited at the prospect of having thousands of small air vehicles buzzing around at low altitude between skyscrapers in large cities.

alberchico

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 14 January 2014

- Messages

- 707

- Reaction score

- 1,513

View: https://mobile.twitter.com/jobyaviation/status/1558109673567420418

This graphic shows the progress towards eventual certification. They currently still have a long way to go. The fact that the FAA still hasn't published exactly what the certification standards are going to be isn't helping either.

This graphic shows the progress towards eventual certification. They currently still have a long way to go. The fact that the FAA still hasn't published exactly what the certification standards are going to be isn't helping either.

This Transformers-Like eVTOL Concept Is One Step Closer to Hitting the Skies

Toronto-based company behind the innovative technology announced that they had completed construction of a 50% scale of the Cavorite X5

- Joined

- 24 November 2008

- Messages

- 1,549

- Reaction score

- 2,612

Disc loading!

This Transformers-Like eVTOL Concept Is One Step Closer to Hitting the Skies

Toronto-based company behind the innovative technology announced that they had completed construction of a 50% scale of the Cavorite X5robbreport.com

Bristow orders of up to 55 BETA Technologies ALIA-250 eVTOL aircraft

Bristow orders of up to 55 BETA Technologies ALIA-250 eVTOL aircraft. Bristow group has placed firm order five electrically powered vertical take off and landing alia 250 aircraft

Bjorn’s Corner: Sustainable Air Transport. Part 28. Vectored thrust VTOLs. - Leeham News and Analysis

July 15, 2022, ©. Leeham News: We started the analysis of the market’s most prominent VTOLs with multicopters last week. Now we continue with vectored thrust VTOLs. The most known exponent for vectored thrust VTOLs is Joby Aviation’s... Read More

For the Joby S4, we have a hover thrust need of 22kN/5,000lbf, whereas forward flight requires 1,5kN to 2kN/350lbf to 450lbf, depending on flight altitude and speed

I think that this quote clearly shows the severe limitations of eVTOL.

The trust- and energy requirements for VTOL and horizontal flight are very different.

Joby has reached a range of 150 miles with VTOL (1x start, 1x landing) but from the quote above it seems that the range with 2 VTOL (2x start, 2x landing) would be rather "zero". The energy requirements for VTOL are so large that even Joby would have nearly no range left with 2 vtol starts without charging the batteries after every flight.

I hope that I miss something. Otherwise from my point of view eVTOL is not really practical.

Similar threads

-

Russia is working on a VTOL Fighter for the 21st Century

- Started by philipp7

- Replies: 4

-

-

-

Japanese 2050 Space Elevator project (Obayashi Corporation)

- Started by Grey Havoc

- Replies: 127

-

Powerpoint engineering and the downfall of quality

- Started by Orionblamblam

- Replies: 61