- Joined

- 25 June 2009

- Messages

- 14,754

- Reaction score

- 6,155

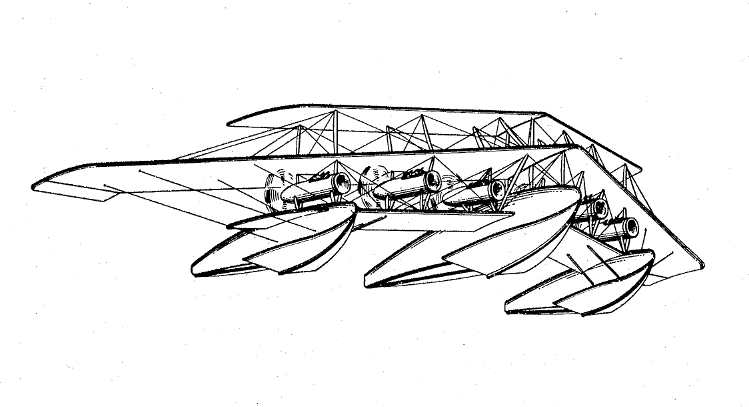

Ever since 1911, Glenn H. Curtiss constantly dreamed of an airplane which would become a "family car of the air". His last efforts in this direction was a "flying wing" biplane with a pusher propeller, the configuration of which was very much like that of the Dunne D.8 of 1911.

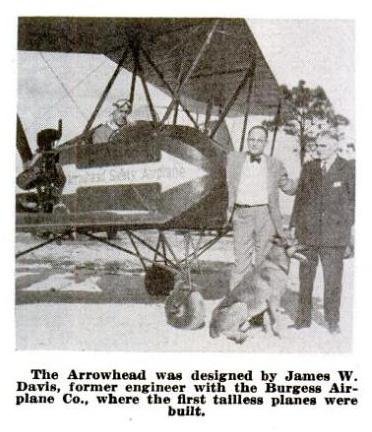

The similarity to the Burgess-Dunne designs of 1914-1916 was not coincidental, since an assistant designer on the project was one J.W. Davis, formerly of the Burgess Aircraft Company of Marblehead, Massachusetts. The design claimed the interest of Glenn H. Curtiss, with whom Davis was connected in real estate development. Contrary to what some publications claimed at the time, Curtiss was not involved in the design of the aircraft. The main designer and builder was former U.S. Marine Major B.L. Smith, who described his design as a flying wing that he hoped would be "economical and safe, in which pilots can be taught to fly in a short length of time at low cost.

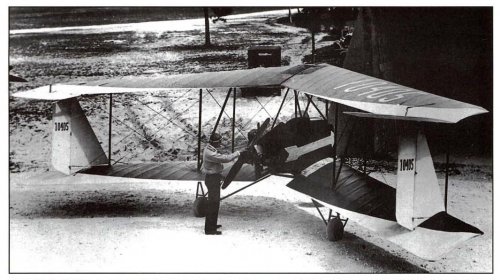

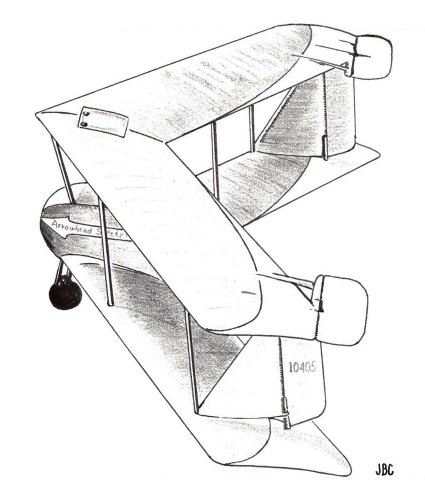

With power derived from a three-cylinder Szekely engine and a landing speed of only 19 miles per hour, the 35-foot-span flying wing, with its 30° sweep, was designed so as not to spin, loop or dive. Smith's B-2 Arrowhead revived Curtiss's dream of a "flivver service" aircraft to be produced in quantity that would appeal to the thousands of potential buyers whom he believed would be willing to spend $1,000 for it.

Curtiss arranged for the plane to be flight tested at Miami. However, before the Arrowhead took to the air on its initial flight, Curtiss died at Buffalo, N. Y. in the late summer of 1930. The flying wing, also dubbed the "Miami Tailless" [10405]*, first flew on a Sunday afternoon at the Miami Municipal Airport and had logged no less than 34 flights by the end of 1930. After Curtiss's death, however, interest waned. B. L. Smith's Safety Aircraft Corp. never placed the Arrowhead on the market and both the company and the design subsequently slipped into oblivion.

* Smith had built another B-2 before, the "Miami Tailless" — registered [X899Y] — but its history is not known.

From the May 1931 issue of Popular Aviation (the magazine that later became Flying):

Useful sources and resources:

The similarity to the Burgess-Dunne designs of 1914-1916 was not coincidental, since an assistant designer on the project was one J.W. Davis, formerly of the Burgess Aircraft Company of Marblehead, Massachusetts. The design claimed the interest of Glenn H. Curtiss, with whom Davis was connected in real estate development. Contrary to what some publications claimed at the time, Curtiss was not involved in the design of the aircraft. The main designer and builder was former U.S. Marine Major B.L. Smith, who described his design as a flying wing that he hoped would be "economical and safe, in which pilots can be taught to fly in a short length of time at low cost.

With power derived from a three-cylinder Szekely engine and a landing speed of only 19 miles per hour, the 35-foot-span flying wing, with its 30° sweep, was designed so as not to spin, loop or dive. Smith's B-2 Arrowhead revived Curtiss's dream of a "flivver service" aircraft to be produced in quantity that would appeal to the thousands of potential buyers whom he believed would be willing to spend $1,000 for it.

Curtiss arranged for the plane to be flight tested at Miami. However, before the Arrowhead took to the air on its initial flight, Curtiss died at Buffalo, N. Y. in the late summer of 1930. The flying wing, also dubbed the "Miami Tailless" [10405]*, first flew on a Sunday afternoon at the Miami Municipal Airport and had logged no less than 34 flights by the end of 1930. After Curtiss's death, however, interest waned. B. L. Smith's Safety Aircraft Corp. never placed the Arrowhead on the market and both the company and the design subsequently slipped into oblivion.

* Smith had built another B-2 before, the "Miami Tailless" — registered [X899Y] — but its history is not known.

From the May 1931 issue of Popular Aviation (the magazine that later became Flying):

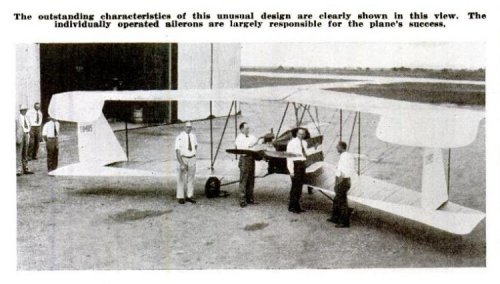

To say the least it is an unusual craft — a tailless, pusher type — and far different from the appearance of the conventional plane. The late Glenn Curtiss was exceedingly interested in and devoted considerable time during the latter days of his life to this design. He called it the future "Air Flivver".

The plane is a biplane, with a three-wheel landing gear. The wings are mounted with a sweepback of approximately 30 degrees. The ship derives its name of "Arrowhead" from the lack of fuselage. A short cockpit and engine nacelle is designed to carry any engine of from 25 to 50 hp.

The principles of governing the practical application of inherent stability in tailless airplanes were first discovered by Lieutenant Dunne, of the British Army. Under his direction a series of experiments to determine the value of the idea were carried out in England. At Marblehead, Mass., a number of tailless airplanes embodying the Dunne ideas were constructed by the Burgess Airplane Co. in 1913-15.

These planes were put through severe tests and conclusively demonstrated that inherent stability and simplicity in flying technique were to be had in this type.

Though crude as to constructional detail, and inefficient from an aerodynamical standpoint, these early planes had inherent stability and ease of flying characteristics which marked them as a thing apart from the other planes of the day.

The advent of the World War put a stop to the experimental development work on this highly interesting and unique type of aircraft. Recently, however, interest in the tailless plane has been rearoused, and today extensive experiments are under way in both England and Germany.

The first plane of this type to be built in the United States since the World War was flown at the All-American Air Races at Miami, in January, 1931. Considerable attention was attracted to the unique plane and its performance.

Commercial production of the Arrowhead tailless plane has been undertaken and the program announced by the company calls for immediate construction of three or four experimental ships.

All of these designs are concentrated around the one basic type -the tailless airplane. Radical improvements in the system of controls, the landing gear, passenger comfort and safety, and economy of upkeep and operation are embodied in the construction.

Several of the specific improvements which have been incorporated into this group of tailless planes are these:

First and most important are the aerodynamical characteristics which are inherently a part of the tailless plane. Absolutely dependable inherent stability in any weather, freedom from any tendence to stall or nose dive, the impossibility of going into a tail spin, and the general incapability of getting into any dangerous maneuver requiring the skill and judgment of an expert pilot to recover from.

To some extent these features were to be found in the first group of Dunne machines built many years ago. In the present design these typically safe features are amplified and improved upon and at the same time a marked improvement in flying efficiency is obtained by the use of the later type of aerofoil sections.

The only serious objection which was ever brought up in connection with the tailless Dunne planes has been entirely overcome by radical changes and improvements in the ailerons and their controlling mechanism.

These improvements involve the use of split ailerons, so hooked up to the control levers that the normal pitch and banking and steering maneuvers can be accomplished, either singly or in combination, by the sole manipulation of the ailerons themselves.

Another point in favor of the tailless plane is the reduced time necessary to learn to operate it. On account of the instinctive ease in the method of handling the controls, coupled with its incapability of assuming dangerous attitudes while in flight, the amount of time required for flying instruction is cut by one-half or to onequarter of that necessary in other types of planes.

The Arrowhead Safety plane is an unbelievably simple machine to fly, and one that very nearly approaches the fool-proof plane. It is less intricate in construction, and many parts are eliminated entirely, at a proportionate lowered cost of production.

The landing gear is of a very simple type, utilizing Goodyear air wheels.

The pusher location of the motor provides a vastly safer installation in case of fire than the conventional tractor offers. Of special interest in connection with the employment of pusher propellers is the exceptional degree of visibility obtained.

The pilot and passengers have an unobstructed view forward, to the side and to the rear. There is nothing whatever to obstruct the pilot's view in any direction, which contributes in no small measure to the facility with which easy and safe landings may be negotiated. There are no blind spots.

With the use of the pusher type of propeller there are several other advantages. A propeller with no part of the airplane behind it is more efficient than one in front.

The truth of this is apparent when it is remembered that in a tractor machine the entire fuselage and tail surfaces and a portion of the wings and landing gear are traveling in the rapidly moving blast of air from the propeller, thereby increasing the resistance of these elements some twenty to thirty per cent.

Again, when the motor is mounted at the rear end of a short fuselage, it is comparatively easy and simple to silence the harrowing bark of the exhaust. Complete and perfect silencing can be obtained without serious loss in efficiency, just as is done today in the modern motor cars.

The Arrowhead Safety plane is exceptionally compact having a wing spread of only 25 feet, an overall length of 17 feet, with a total height of 9 feet. It weighs only 512 pounds empty, seats a pilot and student side by-side, and has dual controls.

The tailless airplane is not "just another airplane" but something new and startling. It has numerous points of superiority, is safer and more stable and is vastly easier to fly. With all these points in its favor, plus the lower cost to manufacture and consequently cheaper price at which it can be purchased, it may easily be the coming "Flivver of the Air", as Mr. Curtiss predicted.

Useful sources and resources:

- Wings in the Sun by William C. Lazarus

- Popular Aviation, May 1931

- Popular Aviation, May 1932

- The Vintage Airplane, December 1974

- The Vintage Airplane, January 1975

- The Vintage Airplane, December 1992

- The Century of Flight website:

http://www.century-of-flight.net/Aviation%20history/flying%20wings/early%20US%20flying%20wings.htm

- Rare footage of the aircraft can be watched here:

http://www.criticalpast.com/video/65675026885_Arrowhead-Safety-Plane_trees_runway_clouded-sky