My opinion:

During the critical days of 1940 the 'Panic Effect' boosted numerous interim solutions to increase the number of fighters available: A.A. Bage, the Percival chief designer, proposed to build a version of the Mew Gull armed with two 0.303 in Vickers Mk.II machine guns. The projected light fighter, called Percival P.32 AA, would have 7.62 m wingspan, 6.57 m overall length and 1,087 kg maximum weight. But it was rejected in favour of the Miles M.24, the single-seat version of the Miles Master, armed with eight Brownings, capable of flying at 370 kph and with handling characteristics similar to those of the Hurricane.

During the Battle of Britain some Tiger Moth training biplanes were equipped with bombs of up to 110 kg and the Percival Proctor prototype P5998 radio-trainer were also converted into anti-invasion light bomber with sixteen 20 lb bombs under the wings.

As a result of a study conducted by the Air Ministry between 1933 and 1934, it was established that, at the high speeds reached by the monoplane fighter, in future combats the target should be destroyed with a burst of just two seconds. To achieve this effect with the standard Colt-Browning Model 1934 machine gun, a fighter should be armed with at least eight of these weapons.

This study considered impossible a combat between two fighters flying at 500 kph and it was not foreseen that the Germans could develop one capable of flying to England. Consequently, the RAF concentrated its efforts in the interception of bombers, developing rigid flight training techniques that were terribly ineffective in 1939.

During the Spanish Civil War, international observers found that the Soviet fighters armed with four PV-1 machine guns usually failed in their tries to intercept the last generation of German bombers that, helped by the Nazi propaganda and the hysterics of the French press, acquired a reputation of invulnerability.

In France, the Hurricanes of the B.E.F. proved how difficult it was to shoot down a Heinkel He 111 with 270 kg armour in 1940. The British pilots often exhausted their 2,600 ammunition rounds without obtaining visible results while the Heinkels returned to their bases with more than 100 impacts of 7.7 mm and were repaired in a few days. These experiences influenced the design of the cannon armed Hurricane Mk.II and Spitfire Mk.V.

The British had acquired the manufacturing rights of the 20 mm Hispano-Suiza H.S. 404 cannon, with explosive shells, but its installation on the wings of fighters was problematic. The weapon had been designed as an integral part of the Hispano-Suiza H.S.12 Y-31 engine and lacked structural strength to act independently. The adaptation was difficult, during the Battle of Britain some Spitfires Mk.I of the 19th Sqn. experimentally equipped with two Hispano Mk.I, suffering numerous stoppage problems. The RAF avoided its usage until the appearing of the Mk.II in the summer of 1941.

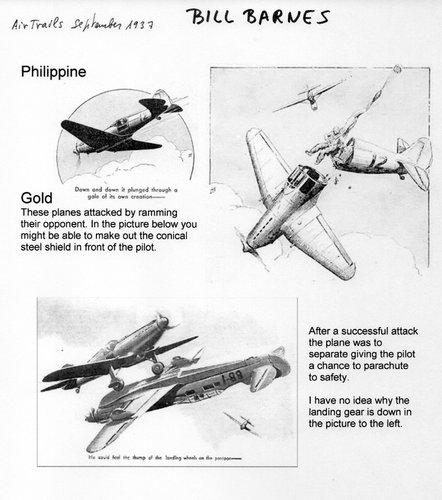

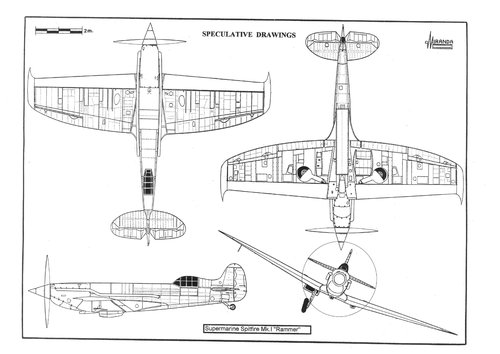

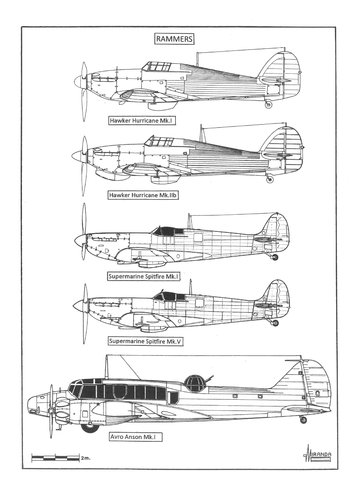

Several methods were considered to mitigate this situation, including air-to-air bombing and rockets vertically fired from the rear fuselage of the Hurricanes. Another idea was the ramming, inspired in the Soviet Taran tactics developed in Spain and Khalkin Gol that assured the destruction of an enemy bomber by collision. In the summer of 1940 the British pilots were forced to resort to ramming in some extreme combats, destroying four Bf 109, two Do 17, one Ju 88, one Bf 110, one Fiat C.R. 42 and one He 111.

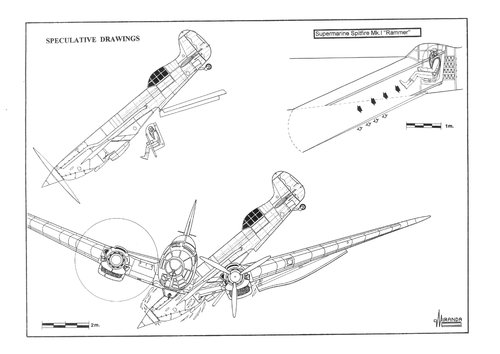

The ramming sometimes happened accidentally, due to miscalculation of distances by the attacking aircraft, or because the pilot had been injured or killed by the defensive fire of the attacked aircraft. At other times, it was a desperate measure consequence of the malfunction of arms in a conventional attack made from behind. The impact used to occur at low speed, between 40 and 80 kph, because both aircraft were flying in the same direction, with the propeller of the attacking plane acting as a circular saw on the tail surfaces of the attacked plane. The rammer usually suffered damages in the propeller, engine bearings and engine cowling and the survival rate of the pilot used to exceed 50 per cent with a good chance of making a glide landing.

When ramming large aircraft, it was more effective to target the fuselage section between wing and tailplane to sever control cables, but the side attack manoeuvre required a very precise calculation of relative speeds that only very expert pilots could perform. The impact, between 300 and 450 kph, used to boot a wing of the attacking aircraft that fell into an uncontrollable flat spin; the pilot was violently thrown in opposite direction to the damaged wing, getting wounded or shocked and with survival possibilities below 25 per cent because the fuselage airframe tended to deform, rendering the opening of the cockpit very difficult.

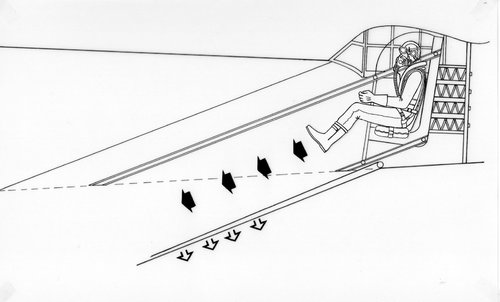

The most effective ramming, and also the most extreme solution, was the head-on-attack, a manoeuvre that Japanese pilots termed Tai-atari (body crashing) in which both aircraft crashed at a joint speed close to 1,000 kph with decelerations of up to 100 g. No one could survive an impact like this by which the rammer embedded into the nose of the bomber and both aircraft fell intertwined. Any airplane could be used for this task if it had enough ceiling and speed to reach the target. The main problem was the survival of the pilot after a collision, in a time when the ejector seats did not exist.

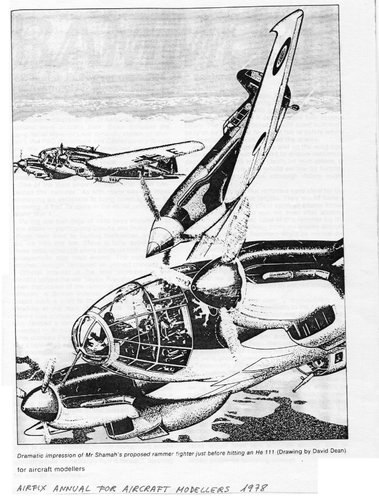

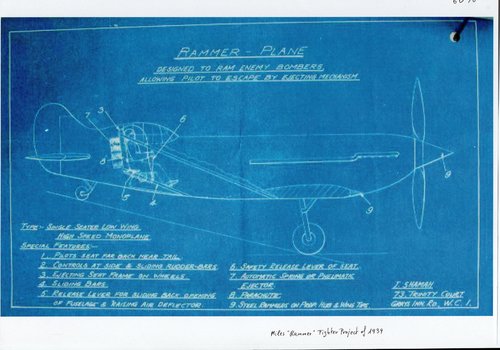

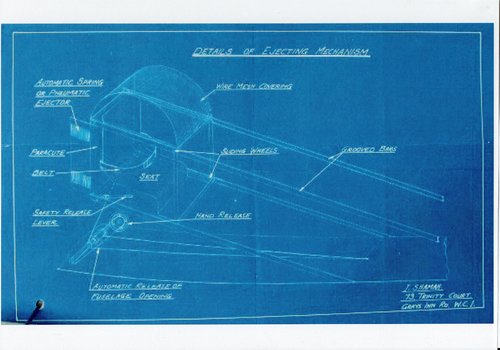

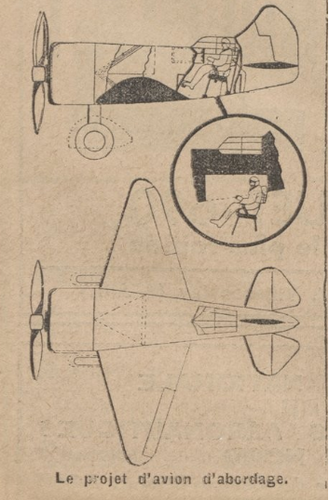

On May 1939, the British inventor Mr. I. Shamah proposed the transformation of a standard fighter into a specialised rammer to the firm Phillips & Powis (later on known as Miles). The modification included the replacement of the guns by an armoured wing leading edge, the installation of steel rammers in the propeller hub and wingtip and one downwards ejector seat located over a ventral hatchway. The idea was considered in 1940, due to the shortage of experienced pilots that mastered the technique of the deflection shooting. Out from the 2,330 fighter pilots who fought against the Luftwaffe between July and November, only 900 managed the destruction of an enemy aircraft, almost always by surprise and firing from less than 200 m.

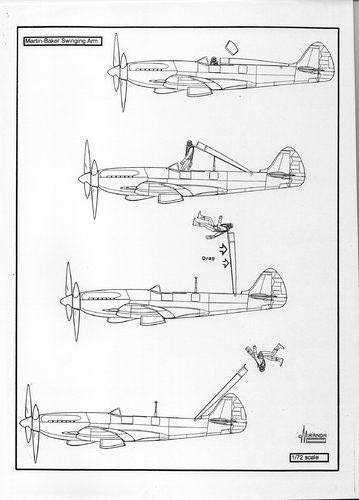

By 1943 the increasing speed reached by the fighters created many difficulties for bailing out, as the air pressure acting over the pilot tended to reintroduce him in the cockpit or to impact against the tail surfaces. In the Spitfire Mk.21 the plan was to install the 'swinging arm', a Martin-Baker invention, to help the pilots overcome the air pressure at high speeds. The upper part of the fuselage detached itself to form an articulated arm that extracted the pilot from the cockpit by means of two hooks inserted in the parachute harness. The arm was actioned by powerful springs and by the air drag, rotating around a hinge located at the base of the tailfin, launching the pilot backwards over the tail surfaces. The project was started in 1944 although it was finally decided to use the seat fitted with an explosive catapult as it was lighter and required less modifications in the airframe.

The Battle of Britain was not the only moment of panic experimented by the RAF however. Between June and September of 1944 had to cope with the attack of 11,700 flying bombs.

In May 1943 the Allies intelligence services discovered the existence of a German catapult-launched missile that was being developed at Peenemünde-West test centre. In August, an air-launched prototype of pilotless airplane of the Karlshagen research centre crashed on Bornholm-Denmark and some pictures, taken by the Resistence, came into the hands of the Allies.

In September the photographic reconnaissance carried out by Mustang Mk.III, Mosquito PR IV and Spitfire PR XI located 133 'ski shaped buildings' with axis pointing directly toward London. They were launch ramps built for the new cruise missiles V-1 manufactured by the firm Fieseler, under the designation Fi 103.

The autopilot of the flying bombs, designed to attack targets the size of a city, was not accurate enough to achieve impacts on Normandy beach heads, or in the ports in southern England from where the supplies were sent to the armies of the Allies.

But the British did not know that and during the weeks preceding the 'D-Day', launched a desperate offensive against the V-1 launch sites and storage buildings built between Cherbourg and Calais. Using all available aircraft, capable of carrying bombs or rockets, they were able to destroy a 25 per cent of the facilities, delaying the release of the first missiles until a week after the Normandy landings.

The British defences had been continually reinforced since 1940. In June 1944 they consisted of 100 radar stations, some 2,000 barrage balloons and 2,729 anti-aircraft guns shooting proximity-fuse shells. Many batteries located between Dover and Hastings were equipped with a predictor fire-control radar system.

To face the 'robot offensive' the defences of the 'Operation Diver' was formed by four lines: long range fighters, operated from the southeast of England to near the French coast; the anti-aircraft artillery located in the south coast of England; the area between the coast and London, covered by high performance interceptors and the urban areas protected by balloons barrages.

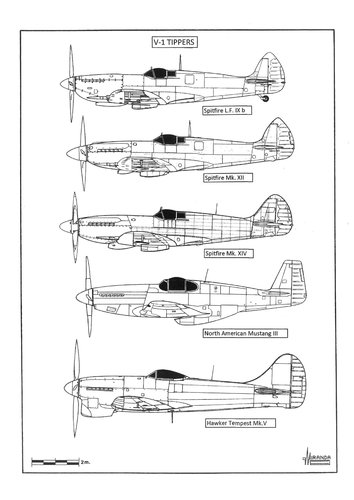

The aerodynamic drag of the V-1 airframe was higher than anticipated, due to low standards of manufacturing, decreasing from projected 900 kph to the real 640 kph. Fortunately for the Allies this made the new missile susceptible to be intercepted by conventional fighters.

In the outward perimeter operated the Mustangs Mk.III of Squadrons 129, 306 (Polish), 313 (Polish) and the Mosquitoes FB Mk VI of the 418th Canadian Squadron. By night, Mosquitoes NF. Mk VII of Squadrons 29 and 465 (Australian), the NF. Mk XII of the 488th Sqn (New Zealander), the NF. Mk XIII of Squadrons 96, 264 and 409 (Canadian), the NF. Mk XVII of the 125th Sqn, the NF. Mk XVIII of the Squadrons 25 and 68, the NF. Mk XIX of the 157th Sqn and the Northrop P-61 Black Widows of American Squadrons the 422nd and 425th took part in the operations.

The Spitfires Mk IX of Squadrons 1, 165, 274, 453 (Australian) and 610, Spitfires Mk XV of the 41st Sqn, Tempest Mk V of the Squadrons 3, 56, 80, 274, 486 (New Zealander) and 501 and Meteors Mk I jet fighters of the 616th Squadron operated in the inner area.

The V-1 had a reduced frontal area equivalent to half of the Bf 109, an engine with the diameter of a dish, a mechanic pilot fitted in a shoe box and a steel airframe. It was very difficult to shoot down. As they were camouflaged, it was very difficult to distinguish them from the landscape when over land. Over sea and at low altitude, the estimated height over the surface in diving attack left very little margin to the pilots. By night, the outburst of the pulsejet was visible from 24 km and gave false range measurements. Some Mosquito pilots, dazzled by the shine, shot from 100 m and one lucky P-61 survived the blast of a V-1 just 46 metres from its nose.

Flying at 725 kph, a Tempest had just two seconds to dodge the debris produced by the explosion of the V-1 which had just shot from 275 m. Some pilots preferred to cross the centre of the explosion where there was less shrapnel, but the inflamed fuel affected the engine, the paint and the fabric covered control surfaces.

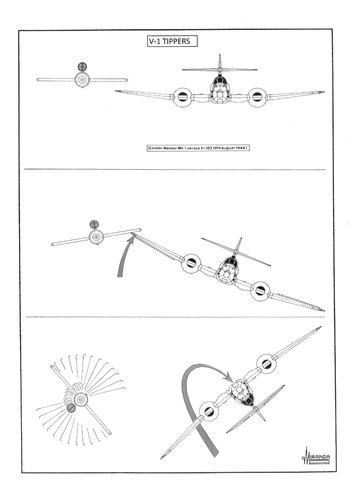

To avoid this, a Mosquito FB VI of the 418 Squadron destroyed a V-1 by simply cutting the missile trajectory and putting it out of control with the trail turbulence. On the contrary, a Meteor of the 616th Squadron stroke the missile wing with the fighter wingtip, decontrolling the gyroscopes. This technique, called 'Tipping', required speed and piloting ability and was only used on 17 occasions.

For the Spitfires the game was even more dangerous, due to its lower structural resistance. They used to start the attack with a dive to gain speed, moving on to horizontal flight at 230 m behind the missile to be able to shoot it. The calculation of relative speeds was complicated, and some pilots died when firing from a too short distance.

It was necessary to modify the fighters to make them fast enough to intercept the V-1. Some Tempest and Spitfires Mk XIV were tuned to operate at 11 and 25 psi boost pressures; the Mustang III changed their exhaust by those of the Spitfire engine that generated less drag; the P-47 M Thunderbolts, with 2,800 hp war emergency power boosted engines, were modified halving its armament and fuel capacity and the armour plates were also stipped. To reduce the drag on some Spitfires, wingtips, rear view mirrors and armored glass windscreens were replaced by those of the P.R. versions of curved type. The camouflage paint was also removed to gain some speed. During the 'Operation Diver', between June1944 and March 1945, sixteen squads of interceptors used the new aviation fuel '150 grade' produced in the USA. Out of the 3,957 V-1 destroyed during the 'robot war', 1,785 were shot down by fighters.

![Les_Ailes___journal_hebdomadaire_[...]_bpt6k6554721m_4.jpeg](/data/attachments/173/173493-fc48def1e1162f4cbe74b4794f59f21a.jpg)