You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

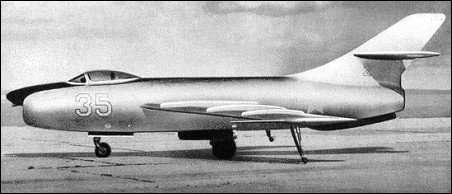

Various Post-War Yakovlev (Yak) Projects & Prototypes

Matej

Multiuniversal creator

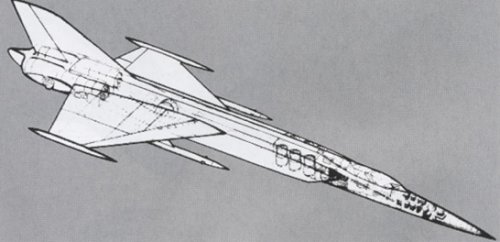

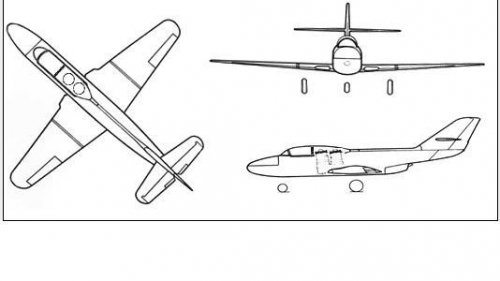

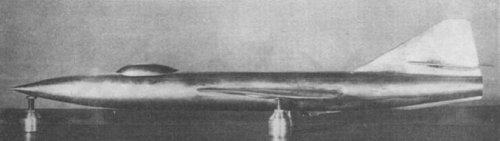

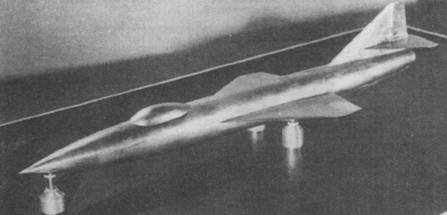

Yep, one of my older drawings  Its CTOL original version, proposed to the PFI competition.

Its CTOL original version, proposed to the PFI competition.

http://www.hitechweb.genezis.eu/fightersSF01_soubory/Jak-45I.jpg

http://www.hitechweb.genezis.eu/fightersSF01_soubory/Jak-45I.jpg

thewanderingmind

Werfless

- Joined

- 2 August 2006

- Messages

- 25

- Reaction score

- 6

That Yak-45 has some nice lines. It looks good enough to possibly have made it into production if things hadn't collapsed... Never saw this one before. Thanks, Hesham and Matej!

Matej

Multiuniversal creator

Production? Never! Yak-45 was evaluated as a crap compared to MiGs and Sukhois PFI proposals. It was underpowered, armed with only four missiles and conceptualy on the level of Messerschmitt Me-262 thirty years back.

thewanderingmind

Werfless

- Joined

- 2 August 2006

- Messages

- 25

- Reaction score

- 6

I bow to the master...

- Joined

- 27 December 2005

- Messages

- 16,873

- Reaction score

- 21,513

Yes, the Yak-45 combined conceptual obsolescence with technical incompetence. Yakovlev claimed 450m/s initial climb rate for it, which Sukhoi's Oleg Samolovich contemptuously dismissed as nonsense: 450m/s is 1620km/h which was higher than the level speed at low altitude! None of the figures from the brochure add up correctly.

Only his political importance sustained Yakovlev's bureau's participation in military competitions after the disastrous Yak-28 family.

Only his political importance sustained Yakovlev's bureau's participation in military competitions after the disastrous Yak-28 family.

hs1216

ACCESS: Confidential

- Joined

- 4 October 2006

- Messages

- 110

- Reaction score

- 23

Why exactly did Yakovlev stay with the old under wing sling engines?

Does anyone see the irony in the fact that most of Yak’s 60’s and 70’s fighter designs use the engine layout of the ME-262, despite the fact Yakovlev used the “it’s a ME-262 copy” argument with Stalin, to screw over his competitors like Sukhoi in the late 1940’s. :

Does anyone see the irony in the fact that most of Yak’s 60’s and 70’s fighter designs use the engine layout of the ME-262, despite the fact Yakovlev used the “it’s a ME-262 copy” argument with Stalin, to screw over his competitors like Sukhoi in the late 1940’s. :

It seems that the WWII Yak-2 and Yak-4 were no better. I remember a Fana article on the subject - political pressure and crap designs led to operational flying coffins, particularly against the Germans :-[

The Forger was not a fighter, rather a joke ;D

Bad luck, Yakovlev produced its only valuable design - the Yak-41 freestyle- at the end of the cold war.

The Forger was not a fighter, rather a joke ;D

Bad luck, Yakovlev produced its only valuable design - the Yak-41 freestyle- at the end of the cold war.

(I'm not sure if this isn't more suitable for General Aerospace Discussion or The Bar but I've posted it here because the comments that inspired it are in this thread)

While Aleksandr Yakovlev was undoubtedly a political animal and may well have used rather ruthless, underhand methods to further his own career and aircraft designs, I'm puzzled by the unflattering comments in this thread regarding the Yak-28 and Yak-36/38.

First flown in 1952, the Yak-25's evolutionary descendants (including the Yak-28) were still operational in the mid Eighties and some of the reconnaissance/ECM machines survived the break up of the Soviet Union. To quote Bill Gunston, the Yak-25 "not only restored Yakovlev's reputation as a designer of successful combat aircraft but also led to a prolific and important family of derivative aircraft".

The last of these derivatives, the Yak-28, was built in reasonable numbers (from Yefim Gordon's OKB Yak - 435 interceptors, 183 trainers, 183 reconnaissance/ECM, 334 bombers plus an unspecified number of early Yak-28 and Yak-28B bombers and development aircraft) and the basic airframe could be successfully adapted for widely different roles.

The bombers, designed for supersonic high altitude flight, fell victim to changes in circumstances requiring operation at low altitudes and the Yak-28 generally had a relatively high attrition rate which investigation suggested was mostly due to pilot error, but neither of these circumstances was the fault of the design.

Given this, I don't understand how the Yak-28 family could be described as "disastrous".

Also, as far as I'm aware, the Yak-36M/Yak-38 "Forger" was never designed as a fighter but as a high subsonic, light attack aircraft with a secondary capacity to destroy enemy helicopters, AWACS and transport aircraft. Although considerable problems were encountered with the early versions, these had essentially been solved with the introduction of the final Yak-38M production run.

The two issues leading to the demise of the aircraft appear to have been the limited range/payload and loss of interest by the Russian Navy. The first of these could have been easily resolved by the addition of drop tanks but, incredibly, no suitable drop tanks were ever developed and the second was a consequence of the end of the Cold War and budget restraints - again not the fault of the basic aircraft design.

As a newcomer to this forum, maybe I'm missing something, but I'd be interested in other people's views.

While Aleksandr Yakovlev was undoubtedly a political animal and may well have used rather ruthless, underhand methods to further his own career and aircraft designs, I'm puzzled by the unflattering comments in this thread regarding the Yak-28 and Yak-36/38.

First flown in 1952, the Yak-25's evolutionary descendants (including the Yak-28) were still operational in the mid Eighties and some of the reconnaissance/ECM machines survived the break up of the Soviet Union. To quote Bill Gunston, the Yak-25 "not only restored Yakovlev's reputation as a designer of successful combat aircraft but also led to a prolific and important family of derivative aircraft".

The last of these derivatives, the Yak-28, was built in reasonable numbers (from Yefim Gordon's OKB Yak - 435 interceptors, 183 trainers, 183 reconnaissance/ECM, 334 bombers plus an unspecified number of early Yak-28 and Yak-28B bombers and development aircraft) and the basic airframe could be successfully adapted for widely different roles.

The bombers, designed for supersonic high altitude flight, fell victim to changes in circumstances requiring operation at low altitudes and the Yak-28 generally had a relatively high attrition rate which investigation suggested was mostly due to pilot error, but neither of these circumstances was the fault of the design.

Given this, I don't understand how the Yak-28 family could be described as "disastrous".

Also, as far as I'm aware, the Yak-36M/Yak-38 "Forger" was never designed as a fighter but as a high subsonic, light attack aircraft with a secondary capacity to destroy enemy helicopters, AWACS and transport aircraft. Although considerable problems were encountered with the early versions, these had essentially been solved with the introduction of the final Yak-38M production run.

The two issues leading to the demise of the aircraft appear to have been the limited range/payload and loss of interest by the Russian Navy. The first of these could have been easily resolved by the addition of drop tanks but, incredibly, no suitable drop tanks were ever developed and the second was a consequence of the end of the Cold War and budget restraints - again not the fault of the basic aircraft design.

As a newcomer to this forum, maybe I'm missing something, but I'd be interested in other people's views.

- Joined

- 27 December 2005

- Messages

- 16,873

- Reaction score

- 21,513

Lets talk about the Yak-28P and Yak-28B/L/I separately.

The Yak-28P basically got a free ride to production not on its merits but due to the appalling reliability of the AL-7F engine which powered the Su-9/11 in the early 1960s. Late production AL-7F managed to struggle to 100, 150, and finally 200 hours service life (not TBO!).

More than half of the 20 Su-9s lost in the first 18 months of service were due to engine troubles. The only bright spot in fighter engine production in the USSR at this point was the R-11-300 engine, which was proving reasonably reliable in the MiG-21. Therefore Su-9 production was terminated and Su-11 production drastically cut, in favour of the Yak-28P (which, by virtue of using the R-11-300 and being twin engined was thought much safer) and MiG-21 developments.

It is important to realise that the USSR had just had its own equivalent of the Sandys White Paper. In 1958-59 35 aircraft projects and 21 engine projects were cancelled as obsolete in the new "missile age". Therefore only "modifications" of existing designs were permissable. The PVO were deeply unhappy with the Su-9 and turned to the Yak-28P instead, which as a modification of an existing type would be allowed into production. Also, the engine arrangement of the Su-9 gave too little room for an effective radar to be fitted, and the Yak-28P would fix this.

In service Yak-28P proved almost as unreliable as the Su-9. Its engines were too widely spaced to help in the engine-out situation, and ironically some problems surfaced with R-11F2-300 reliability . Its performance was distinctly lacking compared to the Su-9 - ceiling and top speed were much lower. It suffered from dangerous aileron reversals. On the bright side range was longer, and the radar (when it worked, which wasn't very often) superior.

924 Su-9 and 72 Su-11 were built. By contrast, only 436 Yak-28Ps were built in 4 years of production. Replacing the Yak-28P, 1,247 Su-15s were built. With the Su-15, Sukhoi fixed the two problems (engines and avionics) of the Su-9 and quickly replaced the Yak-28P in production. In desperation, Yakovlev sent his son to the Novosibirsk production line in 1964 as it prepared for Su-15 production to obtain details of the new engine intakes, and embarked on a crash redesign of the Yak-28P, called Yak-28-64, with fuselage mounted engines.

Performance of the Yak-28-64 was actually worse even than the production Yak-28P, and it had no chance of displacing the Su-15.

Regarding the Yak-28B/L/I series, the story is similar. Several advanced strike aircraft were under development, like Tupolev's "132" transonic low level bomber, and Yakovlev projects like Yak-35MV. These were cancelled in the late 1950s/early 1960s, and only modifications of existing types were to be considered. Su-7B & Yak-28 were regarded as already completed; therefore they entered service. Neither was entirely satisfactory, and production numbers of both were limited by Soviet standards.

Yak-28 production was very difficult; reliability was poor, the avionics seldom worked, and production kept changing through the production run with 10 different versions in total. Yak28B/BI were built in small numbers only. 111 Yak-28L were built, but the Lotos datalink bombing system was next to useless. Yak28I with Initsiyativa radar was a little better, eventually, once the radar was debugged sufficiently to actually work, and 223 were built.

The Su-17 and (eventually) Su-24 supplanted it.

Perhaps "disastrous" is the wrong word; it did fly, mostly. I meant disastrous in terms of Yakovlev's standing with the armed forces, not really in terms of the aircraft themselves, which were merely obsolete in conception and unreliable in service. No Yakovlev proposals were taken seriously for years afterwards.

Regarding the Yak-36M/38, this was never an operational aircraft. It could be best described as the world's best ejection seat test environment, and helped the Russians to build a really first class ejection seat design in the K-36. The design was flawed by reliance on 3 engines all working at once, something that Soviet engine building technology of the time couldn't provide. Unable to get a custom engine designed, they had to reuse the engines from the MiG-23PD. Just like HSA found with the Harrier, the battle for VTOL to work was to squeeze enough power from the engines to actually lift a worthwhile payload as well as the aircraft. Despite the best efforts of BSEL & later Rolls-Royce, world leaders in engine design, the Harrier still struggled until the invention of STOVL. Yak-36M couldn't really manage it, and the design made short takeoffs less useful than to the Harrier, not least because of the tiny wing sized for minimum weight not lift. It barely lurched off the deck with full internal fuel and a rocket pod under each wing; the idea of it carrying external fuel as well just makes no sense. Yak-38 squeezed enough extra power to make it work more reliably, but didn't fix any of the core problems.

The Russians were quite aware of this, but it gave Yakovlev something to do and gained Navy pilots flying experience (mostly in how to eject, of course).

The Yak-41M is not really much better. It stuck with the same basic powerplant idea, but newer engine technology gave more thrust, which is good. Unfortunately, as they found, vectoring a jet engine in full afterburner downwards results in lots of heat, which is bad, and nasty things happen to the aircraft underbelly if its made from, say, aluminium. If you look at the belly of the Yak-41M it looks like they've scabbed on some steel plating to compensate.Not to mention the state of the runway afterwards. Even the deck of an aircraft carrier could find the experience wearing.

It had the dead weight of 2 lift engines occupying internal space better used for, say, fuel. Yes, it was supersonic, but its aerodynamics weren't exactly going to put Sukhoi/Mikoyan out of the fighter business (tiny wing!). It still had a LOT of work to do to get to a viable operational system when the USSR collapsed.

The Yak-28P basically got a free ride to production not on its merits but due to the appalling reliability of the AL-7F engine which powered the Su-9/11 in the early 1960s. Late production AL-7F managed to struggle to 100, 150, and finally 200 hours service life (not TBO!).

More than half of the 20 Su-9s lost in the first 18 months of service were due to engine troubles. The only bright spot in fighter engine production in the USSR at this point was the R-11-300 engine, which was proving reasonably reliable in the MiG-21. Therefore Su-9 production was terminated and Su-11 production drastically cut, in favour of the Yak-28P (which, by virtue of using the R-11-300 and being twin engined was thought much safer) and MiG-21 developments.

It is important to realise that the USSR had just had its own equivalent of the Sandys White Paper. In 1958-59 35 aircraft projects and 21 engine projects were cancelled as obsolete in the new "missile age". Therefore only "modifications" of existing designs were permissable. The PVO were deeply unhappy with the Su-9 and turned to the Yak-28P instead, which as a modification of an existing type would be allowed into production. Also, the engine arrangement of the Su-9 gave too little room for an effective radar to be fitted, and the Yak-28P would fix this.

In service Yak-28P proved almost as unreliable as the Su-9. Its engines were too widely spaced to help in the engine-out situation, and ironically some problems surfaced with R-11F2-300 reliability . Its performance was distinctly lacking compared to the Su-9 - ceiling and top speed were much lower. It suffered from dangerous aileron reversals. On the bright side range was longer, and the radar (when it worked, which wasn't very often) superior.

924 Su-9 and 72 Su-11 were built. By contrast, only 436 Yak-28Ps were built in 4 years of production. Replacing the Yak-28P, 1,247 Su-15s were built. With the Su-15, Sukhoi fixed the two problems (engines and avionics) of the Su-9 and quickly replaced the Yak-28P in production. In desperation, Yakovlev sent his son to the Novosibirsk production line in 1964 as it prepared for Su-15 production to obtain details of the new engine intakes, and embarked on a crash redesign of the Yak-28P, called Yak-28-64, with fuselage mounted engines.

Performance of the Yak-28-64 was actually worse even than the production Yak-28P, and it had no chance of displacing the Su-15.

Regarding the Yak-28B/L/I series, the story is similar. Several advanced strike aircraft were under development, like Tupolev's "132" transonic low level bomber, and Yakovlev projects like Yak-35MV. These were cancelled in the late 1950s/early 1960s, and only modifications of existing types were to be considered. Su-7B & Yak-28 were regarded as already completed; therefore they entered service. Neither was entirely satisfactory, and production numbers of both were limited by Soviet standards.

Yak-28 production was very difficult; reliability was poor, the avionics seldom worked, and production kept changing through the production run with 10 different versions in total. Yak28B/BI were built in small numbers only. 111 Yak-28L were built, but the Lotos datalink bombing system was next to useless. Yak28I with Initsiyativa radar was a little better, eventually, once the radar was debugged sufficiently to actually work, and 223 were built.

The Su-17 and (eventually) Su-24 supplanted it.

Perhaps "disastrous" is the wrong word; it did fly, mostly. I meant disastrous in terms of Yakovlev's standing with the armed forces, not really in terms of the aircraft themselves, which were merely obsolete in conception and unreliable in service. No Yakovlev proposals were taken seriously for years afterwards.

Regarding the Yak-36M/38, this was never an operational aircraft. It could be best described as the world's best ejection seat test environment, and helped the Russians to build a really first class ejection seat design in the K-36. The design was flawed by reliance on 3 engines all working at once, something that Soviet engine building technology of the time couldn't provide. Unable to get a custom engine designed, they had to reuse the engines from the MiG-23PD. Just like HSA found with the Harrier, the battle for VTOL to work was to squeeze enough power from the engines to actually lift a worthwhile payload as well as the aircraft. Despite the best efforts of BSEL & later Rolls-Royce, world leaders in engine design, the Harrier still struggled until the invention of STOVL. Yak-36M couldn't really manage it, and the design made short takeoffs less useful than to the Harrier, not least because of the tiny wing sized for minimum weight not lift. It barely lurched off the deck with full internal fuel and a rocket pod under each wing; the idea of it carrying external fuel as well just makes no sense. Yak-38 squeezed enough extra power to make it work more reliably, but didn't fix any of the core problems.

The Russians were quite aware of this, but it gave Yakovlev something to do and gained Navy pilots flying experience (mostly in how to eject, of course).

The Yak-41M is not really much better. It stuck with the same basic powerplant idea, but newer engine technology gave more thrust, which is good. Unfortunately, as they found, vectoring a jet engine in full afterburner downwards results in lots of heat, which is bad, and nasty things happen to the aircraft underbelly if its made from, say, aluminium. If you look at the belly of the Yak-41M it looks like they've scabbed on some steel plating to compensate.Not to mention the state of the runway afterwards. Even the deck of an aircraft carrier could find the experience wearing.

It had the dead weight of 2 lift engines occupying internal space better used for, say, fuel. Yes, it was supersonic, but its aerodynamics weren't exactly going to put Sukhoi/Mikoyan out of the fighter business (tiny wing!). It still had a LOT of work to do to get to a viable operational system when the USSR collapsed.

- Joined

- 26 May 2006

- Messages

- 33,449

- Reaction score

- 13,474

Matej

Multiuniversal creator

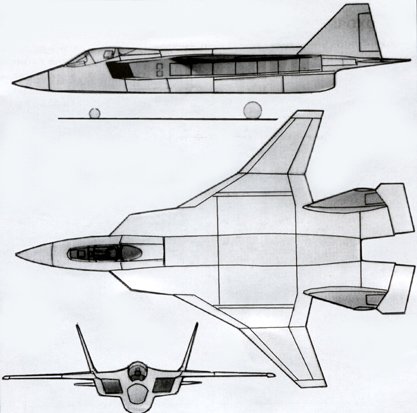

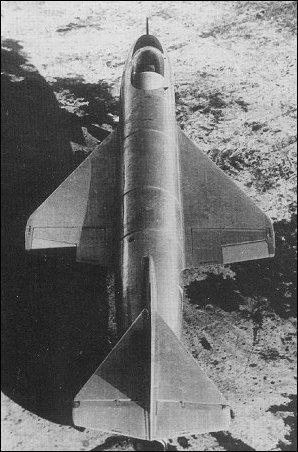

Third picture in hesham´s post no.52 is a big mystery for me. I know this concept as Yakovlev "kashka" but without any other info.

Overscan:

Thanks for the interesting information on the Yak-28 and Yak-36 in your post 51. The books that I have on the Yak-28 and the Yak OKB (by Gunston, Gordon and Komissarov) don't go into detail on the political or engine issues, particularly as they affected competing designs, so I'll have to concede that the Yak-28 may have been somewhat less impressive than I'd assumed until now. Another illusion shattered - - -

I still think that you're a bit harsh on the Yak-38 (its wing wasn't significantly smaller than the Harrier's and apparently it was plumbed for tanks, these were just never manufactured) although I do see the problems presented by reliance on three engines working simultaneously and lugging around lift engines in normal flight.

Regarding ejection seats, Yak figures suggest that 83 Harriers and 25 pilots were lost between 1969 and 1980, compared to 36 Forgers and 4 pilots between 1974 and 1980. The attrition rate isn't that different, given the dissimilar periods, but the pilot fatalities are. If the figures are accurate, does anyone know if the better Soviet survival rate was due to their ejection seats or to the circumstances of the crashes?

Also, I've seen the photograph of the Shcherbakov VSI in Hesham's post 53 before, but I've never come across any specifications or other photos or plans. Does anyone have these or know where they can be found?

Thanks for the interesting information on the Yak-28 and Yak-36 in your post 51. The books that I have on the Yak-28 and the Yak OKB (by Gunston, Gordon and Komissarov) don't go into detail on the political or engine issues, particularly as they affected competing designs, so I'll have to concede that the Yak-28 may have been somewhat less impressive than I'd assumed until now. Another illusion shattered - - -

I still think that you're a bit harsh on the Yak-38 (its wing wasn't significantly smaller than the Harrier's and apparently it was plumbed for tanks, these were just never manufactured) although I do see the problems presented by reliance on three engines working simultaneously and lugging around lift engines in normal flight.

Regarding ejection seats, Yak figures suggest that 83 Harriers and 25 pilots were lost between 1969 and 1980, compared to 36 Forgers and 4 pilots between 1974 and 1980. The attrition rate isn't that different, given the dissimilar periods, but the pilot fatalities are. If the figures are accurate, does anyone know if the better Soviet survival rate was due to their ejection seats or to the circumstances of the crashes?

Also, I've seen the photograph of the Shcherbakov VSI in Hesham's post 53 before, but I've never come across any specifications or other photos or plans. Does anyone have these or know where they can be found?

- Joined

- 29 September 2006

- Messages

- 1,690

- Reaction score

- 1,166

hesham said:Hi,

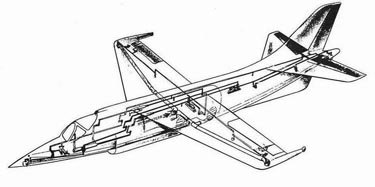

The Yak-V project for VTOL experimental aircraft of early of 1960s.

Very Harrier-like (Or as it's the early 60's, perhaps I should say "Kestrel-like).

Was this to be vectored-thrust only, or vectored rear thrust + lift jets like the Yak-38?

Starviking

Matej

Multiuniversal creator

starviking said:Very Harrier-like (Or as it's the early 60's, perhaps I should say "Kestrel-like).

Was this to be vectored-thrust only, or vectored rear thrust + lift jets like the Yak-38?

Starviking

Experimental plane with vectored thrust only (Kestrel-like) with four nozzles. It was abadoned, because in Soviet union there was not any Pegaus-like engine.

McGreig said:Overscan:

-Snip-

Regarding ejection seats, Yak figures suggest that 83 Harriers and 25 pilots were lost between 1969 and 1980, compared to 36 Forgers and 4 pilots between 1974 and 1980. The attrition rate isn't that different, given the dissimilar periods, but the pilot fatalities are. If the figures are accurate, does anyone know if the better Soviet survival rate was due to their ejection seats or to the circumstances of the crashes?

-Snip-

According to Roy Braybrooks Soviet Combat Aircraft, the Forger had an automatic pilot ejection system called Eskem which ejected the pilot if it noted aberrant aircraft behaviour at low speeds. A very good idea if you ask me. Even if there are a number of false alarms, it would certainly react faster than a human pilot, and without any indecision about whether to wreck the pretty airplane!

Howdy everybody. I love this site, and have had it bookmarked for some time now, and only decided to create an account to view the pictures. Not that I had any objection to being a member, but I think I just did my entire quota of aircraft knowledge in the preceding paragraph, so I won't be posting very often!

- Joined

- 27 December 2005

- Messages

- 16,873

- Reaction score

- 21,513

Well, everyone is welcome to join the site, and you never know, you might find something else useful one day!

The Yak-38 automatic ejection system may well have increased pilot survivability, but I doubt they were flown as hard and often as the Harriers were. Therefore I think the crash rate per flight hour is likely very much in the Harrier's favour.

The Yak-38 automatic ejection system may well have increased pilot survivability, but I doubt they were flown as hard and often as the Harriers were. Therefore I think the crash rate per flight hour is likely very much in the Harrier's favour.

- Joined

- 26 May 2006

- Messages

- 33,449

- Reaction score

- 13,474

Attachments

- Joined

- 26 May 2006

- Messages

- 33,449

- Reaction score

- 13,474

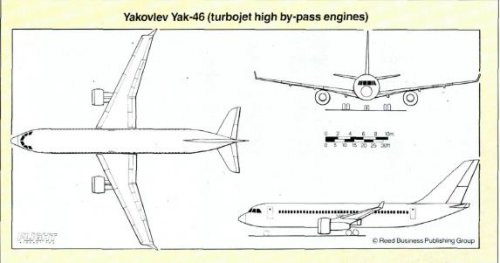

Hi,

also in that site which I discovered it,there was a mystery

project,the YAK 2VK-11,it was a high-altitude supersonic

bomber project of 1956,powered by two VK-11 engines.

also in that site which I discovered it,there was a mystery

project,the YAK 2VK-11,it was a high-altitude supersonic

bomber project of 1956,powered by two VK-11 engines.

- Joined

- 26 May 2006

- Messages

- 33,449

- Reaction score

- 13,474

hesham said:Hi,

also in that site which I discovered it,there was a mystery

project,the YAK 2VK-11,it was a high-altitude supersonic

bomber project of 1956,powered by two VK-11 engines.

I forget that,the old site in this topic spoke about this aircraft;

Yak-2VK-11. Two high-altitude supersonic bomber front, and at

its base - intelligence. Two TRD VK-11 with a thrust of 4500 kg

and 9000 kg at forcing a regime. Government Decision of August

15, 1956 were required to construct five copies bombers and the

first of them present for flight tests in the first quarter of 1958,

in the state - in the fourth quarter of 1958, Razvedchik had to

be present for testing air control in the third quarter of 1958 .

Assigned bomber characteristics: maximum speed of 1300 km / h

(2500 mode, forcing km / h) range from 5% residual fuel 2500 km;

practical ceiling 20000 ... 21000 m run-mileage 1300 m; load

Bombings normal 1200 kg, the maximum -3000 kg. Intelligence

should have the range 2500 22000 m.

And for the new site,there is also the YAK-118,a six-seat

multi-purpose aircraft based on YAK-18T with a Germany

engine.

ucon

ACCESS: Top Secret

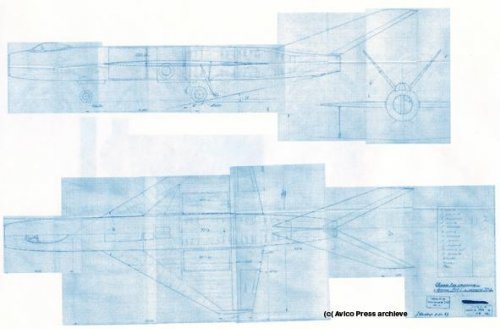

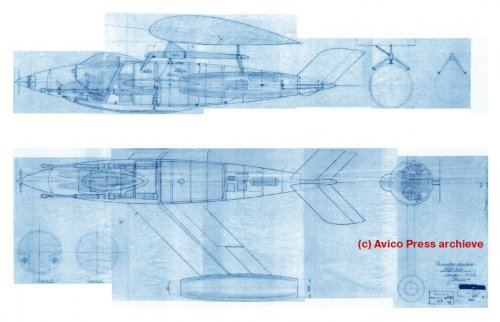

Yak-PVRD project

Yak-ramjet

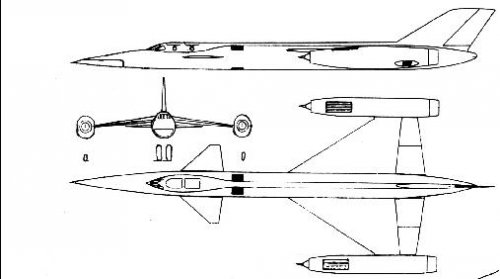

Since the mid 40's in the OKB Yakovlev investigated a large number of schemes jet combat aircraft. Some of them have been implemented in the metal, and the rest can be considered as exploratory, giving answers to certain questions.

The international situation in the years continued to worsen. To counter this, needed a strong defense and supersonic fighter-bombers.

For the design of such an aircraft in the Yakovlev Design Bureau started in late 1947, and only 26 June 1948 L. Schechter presented a draft single-seat fighter-bomber with four ramjet.

Choosing a propulsion system for experimental aircraft was not random, especially at EDO had experience designing and building the Yak-7P, and then the Yak-3RD.

Ramjet - a jet engine, which is continuously fed into the combustion air is compressed by the action of the velocity head. The main advantage of the ramjet is their ability to operate at very high speeds and at higher altitudes than the turbojet, which is determined when the fighter-bomber.

For such engines is characterized by the absence of moving parts, respectively, and the simplicity of design, technology in production and low cost.

However, a significant drawback of the ramjet, which negates all of the benefits is the lack of static thrust and should be forced to start. Yes, and at subsonic speeds these engines were extremely uneconomical.

The project envisaged Yucca with liquid ramjet boosters hanging under swept (45 degrees) wing.

Under the scheme of the plane is a single vysokoplan with four engines and bike chassis, which was followed by the classic series of Yak-25 - Yak-28.

Wingspan was 14.20 m, wing area - 59 m2, the length of the plane 19.82 m span horizontal tail 4, 0 m, track chassis between supporting pillars - 6, 4 pm

Considered options fighter, fighter-bomber and reconnaissance aircraft. Speed performance and massive data known.

Project was not implemented due to complexity with engines.

Sorry for Google translation

Yak-ramjet

Since the mid 40's in the OKB Yakovlev investigated a large number of schemes jet combat aircraft. Some of them have been implemented in the metal, and the rest can be considered as exploratory, giving answers to certain questions.

The international situation in the years continued to worsen. To counter this, needed a strong defense and supersonic fighter-bombers.

For the design of such an aircraft in the Yakovlev Design Bureau started in late 1947, and only 26 June 1948 L. Schechter presented a draft single-seat fighter-bomber with four ramjet.

Choosing a propulsion system for experimental aircraft was not random, especially at EDO had experience designing and building the Yak-7P, and then the Yak-3RD.

Ramjet - a jet engine, which is continuously fed into the combustion air is compressed by the action of the velocity head. The main advantage of the ramjet is their ability to operate at very high speeds and at higher altitudes than the turbojet, which is determined when the fighter-bomber.

For such engines is characterized by the absence of moving parts, respectively, and the simplicity of design, technology in production and low cost.

However, a significant drawback of the ramjet, which negates all of the benefits is the lack of static thrust and should be forced to start. Yes, and at subsonic speeds these engines were extremely uneconomical.

The project envisaged Yucca with liquid ramjet boosters hanging under swept (45 degrees) wing.

Under the scheme of the plane is a single vysokoplan with four engines and bike chassis, which was followed by the classic series of Yak-25 - Yak-28.

Wingspan was 14.20 m, wing area - 59 m2, the length of the plane 19.82 m span horizontal tail 4, 0 m, track chassis between supporting pillars - 6, 4 pm

Considered options fighter, fighter-bomber and reconnaissance aircraft. Speed performance and massive data known.

Project was not implemented due to complexity with engines.

Sorry for Google translation

Attachments

ucon

ACCESS: Top Secret

ucon

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 13 May 2006

- Messages

- 1,039

- Reaction score

- 900

How many new surprises is still unknown

ucon

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 3 June 2006

- Messages

- 2,946

- Reaction score

- 3,155

Great find, ucon.

IMHO the Yak-40 from 1948 seems to be inspired by Junkers Ef prototypes and studies. An comparable example would be the Junkers Ef 126.

IMHO the Yak-40 from 1948 seems to be inspired by Junkers Ef prototypes and studies. An comparable example would be the Junkers Ef 126.

- Joined

- 27 December 2005

- Messages

- 16,873

- Reaction score

- 21,513

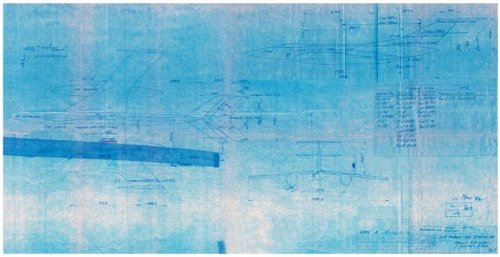

Ucon - those scans are cool, but very hard to make out. Perhaps if you sent me higher res copies I could fix them up?

ucon

ACCESS: Top Secret

Which ones do you mean, Paul?

- Joined

- 27 December 2005

- Messages

- 16,873

- Reaction score

- 21,513

Yak-30 for instance. I imagine you want to restrict size for future publication, but its pretty hard to make out details.

Similar threads

-

-

-

History of aircraft design in USSR 1951-65 / Chapter 10: Yakovlev

- Started by hesham

- Replies: 17

-

-

Yakovlev's Yak-LSh (Yak-25LSh) light "Shturmovik" (1969)

- Started by Stargazer

- Replies: 16