- Joined

- 9 October 2009

- Messages

- 21,973

- Reaction score

- 13,630

The Soviet Military Program that Secretly Mapped the Entire World

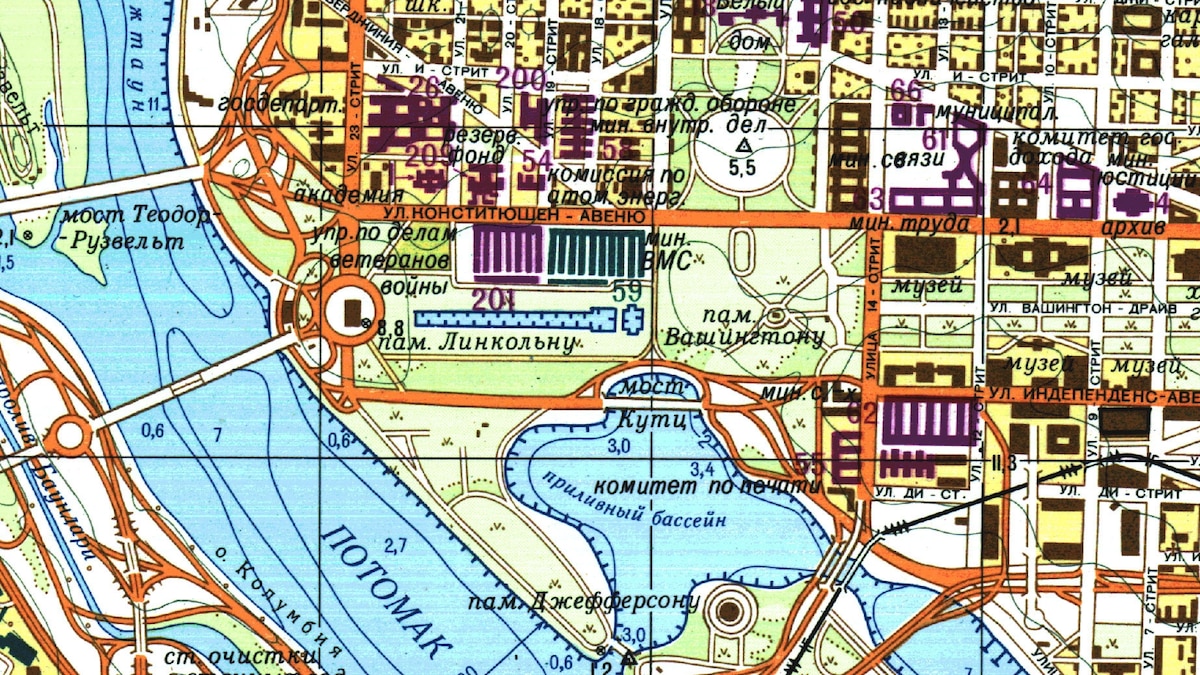

The U.S.S.R. covertly mapped American and European cities—down to the heights of houses and types of businesses.

Inside the Secret World of Russia's Cold War Mapmakers

The Soviet military mapped the entire world, but few have seen the actual, physical maps—until now.

The Red Atlas

Nearly thirty years after the end of the Cold War, its legacy and the accompanying Russian-American tension continues to loom large. Russia’s access to detailed information on the United States and its allies may not seem so shocking in this day of data clouds and leaks, but long before we had...

It was on a consulting trip to Latvia in the early 2000s that he stumbled on a trove of Soviet maps in a shop near the center of the capital city, Riga. Davies struck up a friendship with one of the owners, a tall, athletic man named Aivars Beldavs, and bought an armload of Soviet maps from him every time he was in town.

Back home he’d compare the Soviet maps to the maps made around the same time by the Ordnance Survey, the national mapping agency, and other British government sources. He soon spotted some intriguing discrepancies.

In Chatham, a river town in the far southeast, a Soviet map from 1984 showed the dockyards where the Royal Navy built submarines during the Cold War—a region occupied by blank space on contemporary British maps. The Soviet map of Chatham also includes the dimensions, carrying capacity, clearance, and even the construction materials of bridges over the River Medway. In Cambridge, Soviet maps from the ’80s include a scientific research center that didn’t appear on Ordnance Survey maps till years later. Davies started compiling lists of these differences, and on his trips to Latvia, he started asking Beldavs more questions.

Beldavs, it turns out, had served in the Soviet Army in the mid-’80s, and he used the secret military maps in training exercises in East Germany. A signature was required before a map could be checked out for an exercise, and the army made sure every last one got returned. “Even if it gets destroyed, you need to bring back the pieces,” Beldavs says.

A few years after he got out of the army, Beldavs helped start the map shop, Jana Seta, which sold maps mainly to tourists and hikers. As he tells it, officers at the military cartographic factories in Latvia were instructed to destroy or recycle all the maps as the Soviet Union dissolved in the early ’90s. “But some clever officers found our company,” he says. An offer was made, a deal was struck, and Beldavs estimates the shop acquired enough maps to fill 13 rail cars. At first they didn’t have enough space to store them all. One time, some local kids tried to set fire to a pallet load of maps they’d left outside. But the vast majority of them survived unscathed.

The Soviet maps were just a casual hobby for Davies until he met David Watt, a map librarian for the British Ministry of Defence, in 2004. Watt, it turns out, had encountered Beldavs years earlier and done some investigations of his own. At a cartography conference in Cologne, Germany, in 1993, Watt had picked up a pamphlet from Beldavs’ shop advertising Soviet military topographic maps and city plans. He was stunned.

“If they really were Soviet military city plans, then these were items which four years before were so highly classified that even squaddies in the Red Army were not allowed to see them,” he later recalled. Watt placed an order.

A few weeks later a package was waiting for him at the airport. Inside were the maps he’d ordered—and a bunch more Beldavs had thrown in. Over the next few years, Watt pored over these maps and picked up others from various dealers. The scope of the Soviet military’s cartographic mission began to dawn on him.

They had mapped nearly the entire world at three scales. The most detailed of these three sets of maps, at a scale of 1:200,000, consisted of regional maps. A single sheet might cover the New York metropolitan area, for example.

But they didn’t stop there. The Soviets made far more detailed maps of some parts of the world. They mapped all of Europe, nearly all of Asia, as well as large parts of North America and northern Africa at 1:100,000 and 1:50,000 scales, which show even more features and fine-grained topography. Another series of still more zoomed-in maps, at 1:25,000 scale, covers all of the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, as well as hundreds or perhaps thousands of foreign cities. At this scale, city streets and individual buildings are visible.

And even that wasn’t the end of it. The Soviets produced hundreds of remarkably detailed 1:10,000 maps of foreign cities, mostly in Europe, and they may have mapped the entire USSR at this scale, which Watt estimated would take 440,000 sheets.

All in all, Watt estimated that the Soviet military produced more than 1.1 million different maps.

Last edited: