You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Messerschmitt Bf/Me 210/410 Projects, Prototypes & Derivatives

- Thread starter hesham

- Start date

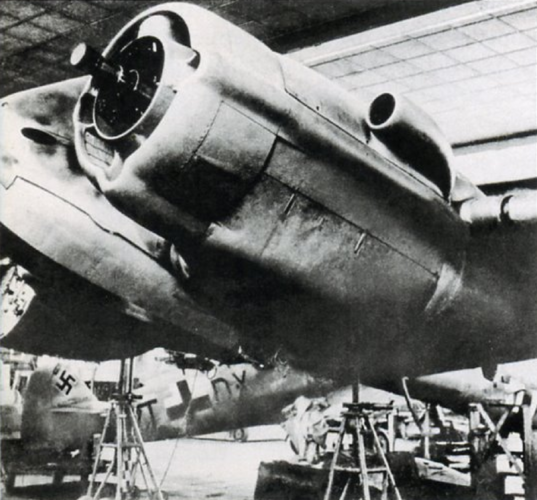

According to info in this book:

the belly fairing was for "Düppel" (Chaff).

By the way, the same book has photos of a DB 603 powered Me 410 as well as drawings of multiple alternate DB 603 fitment options and even a BMW 801 powered version.

the belly fairing was for "Düppel" (Chaff).

By the way, the same book has photos of a DB 603 powered Me 410 as well as drawings of multiple alternate DB 603 fitment options and even a BMW 801 powered version.

- Joined

- 11 March 2006

- Messages

- 8,625

- Reaction score

- 3,805

The term "Nachtstörflugzeug" is interesting indeed, and certainly wasn't used in accordance to the then

used terminology. The "Nachtstörstaffeln" were triggered by unpleasant experiences with their Soviet

counterparts, using Polikarpov Po-2, and used similar aircraft, e.g. Gotha 145. Going low and slow was

essential for that kind of night harassing. Perhaps the Me 410 "Nachtstörflugzeug" should revive the

"Fernnachtjagd", which had been stopped in autumnm 1941 ? Radar wouldn't have been essential , but

probably carrying some bombs, so a pure nightfighter wasn't the ideal aircraft for that task, leading to

that new variant ?

used terminology. The "Nachtstörstaffeln" were triggered by unpleasant experiences with their Soviet

counterparts, using Polikarpov Po-2, and used similar aircraft, e.g. Gotha 145. Going low and slow was

essential for that kind of night harassing. Perhaps the Me 410 "Nachtstörflugzeug" should revive the

"Fernnachtjagd", which had been stopped in autumnm 1941 ? Radar wouldn't have been essential , but

probably carrying some bombs, so a pure nightfighter wasn't the ideal aircraft for that task, leading to

that new variant ?

I could agree if the tactics changed. Flying slow and low wouldn`t fit using high-performance engines like the DB 603, and it would pack 3 canisters of düppel, making it an aircraft intended to operate in a radar-rich environment, excluding therefore the eastern front. According it`s date of design I would bet it was a Unternehmen Steinbock/"Baby Blitz" product, meant for the western front, or the italian front.The term "Nachtstörflugzeug" is interesting indeed, and certainly wasn't used in accordance to the then

used terminology. The "Nachtstörstaffeln" were triggered by unpleasant experiences with their Soviet

counterparts, using Polikarpov Po-2, and used similar aircraft, e.g. Gotha 145. Going low and slow was

essential for that kind of night harassing. Perhaps the Me 410 "Nachtstörflugzeug" should revive the

"Fernnachtjagd", which had been stopped in autumnm 1941 ? Radar wouldn't have been essential , but

probably carrying some bombs, so a pure nightfighter wasn't the ideal aircraft for that task, leading to

that new variant ?

- Joined

- 11 March 2006

- Messages

- 8,625

- Reaction score

- 3,805

IIRC, the Fernnachtjagd was regarded as successful, but mainly by the squadrons, actually flying such missions

only, not by the high command. The night fighters were overstressed anyway, and judging the success of long

range missions over british bomber bases, was difficult, at the best. So, the claims were often regarded as

exaggerated, and such missions axed.

But in 1944, the Luftwaffe had gained much experience about the efficiency of such mission ... because of the RAF,

constantly raiding airfields of German night fighters at night.

So, maybe adopting such tactics was contemplated again ? Probably much more useful, than bombing London

suburbs, though I agree, that this may not have been a valid argument back then ...

only, not by the high command. The night fighters were overstressed anyway, and judging the success of long

range missions over british bomber bases, was difficult, at the best. So, the claims were often regarded as

exaggerated, and such missions axed.

But in 1944, the Luftwaffe had gained much experience about the efficiency of such mission ... because of the RAF,

constantly raiding airfields of German night fighters at night.

So, maybe adopting such tactics was contemplated again ? Probably much more useful, than bombing London

suburbs, though I agree, that this may not have been a valid argument back then ...

Airborne2001

ACCESS: Secret

- Joined

- 19 June 2020

- Messages

- 224

- Reaction score

- 278

I have two questions:

1. Does anyone have data on the specifications of the Me-410B with DB 603G engines?

2. Does anyone have pictures of what the Me-410C and Me-410B would have looked like?

1. Does anyone have data on the specifications of the Me-410B with DB 603G engines?

2. Does anyone have pictures of what the Me-410C and Me-410B would have looked like?

Sorry, this is wrong (I did not have the book with me). I inadvertently mixed it up with the Messerschmitt project P 1099 which in one variant has rearward firing MK 103.In Dan's latest book a very interesting Me 410 Zerstoerer (bomber destroyer) concept is represented with a rearward firing semi-rigid MK 103 gun.

- Joined

- 11 June 2014

- Messages

- 1,541

- Reaction score

- 2,899

I have two questions:

1. Does anyone have data on the specifications of the Me-410B with DB 603G engines?

2. Does anyone have pictures of what the Me-410C and Me-410B would have looked like?

I must admit to only average knowledge of the Me 410 but was the 'B' proposed with DB 603 Gs?

IIRC, the Fernnachtjagd was regarded as successful, but mainly by the squadrons, actually flying such missions

only, not by the high command. The night fighters were overstressed anyway, and judging the success of long

range missions over british bomber bases, was difficult, at the best. So, the claims were often regarded as

exaggerated, and such missions axed.

But in 1944, the Luftwaffe had gained much experience about the efficiency of such mission ... because of the RAF,

constantly raiding airfields of German night fighters at night.

So, maybe adopting such tactics was contemplated again ? Probably much more useful, than bombing London

suburbs, though I agree, that this may not have been a valid argument back then ...

In my opinion, the real reason for abandoning formal intruder operations was practical: cost/benefit ratio. For example, a dozen Me410s of KG51 carried out a successful, impromptu intruder attack on USAAF B-24s returning from Hamm in 1944 (see below) and destroyed 12 out of the 1662 USAAF despatched at the cost of two Me410s: a rate of loss to intruders of about 0.7% for the USAAF vs a 17% loss rate for the Luftwaffe. The latter is simply not sustainable, especially when the US could replace pilots and aircraft and Germany could not.

I'm attaching part of an assessment that I wrote for Chandelle (text and illustrations © 2007-2008 by Robert Craig Johnson. All rights reserved):

"For all the success of the intruder tactic, Luftwaffe adoption of intruder tactics was limited by the exigencies of supply and political necessity. The Himmelbet system was successful in large part because it, for the most part, did not compete for aircraft and aircrew with better established arms of the service. The Messerschmidt Bf110 was thus entirely adequate. But the intruder role required an aircraft and crew capable of locating a point at a considerable distance from home and then operating for an extended period over hostile territory. An altogether larger, bomber-sized aircraft with a highly trained, bomber-type crew was thus essential.

"As it happened,frontline demand for aircraft and skilled aviators far outstripped Germany's ability to produce either in wartime. For all its initial successes, Germany was, relative to its opponents, a fairly small and under-industrialized country with few natural resources and a modest population. It counted on a short war, in which scarcities and wastage could be made up quickly using captured enemy equipment and supplies. The Luftwaffe training organization was dwarfed by its counterparts in the British Commonwealth and the United States. It depended in large part on obsolete or captured French, Czech, and Dutch aircraft and engines for its equipment. When hopes for a short war and an advantageous peace began to evaporate, a tactic that concentrated scarce airframe materials, engines, and trained crews in a few sophisticated, long-range aircraft could not be sustained. As the frontlines began to constrict around Germany, the choice had to be made between a larger, less intensively trained force of fighter pilots and single-seat fighter-bombers—or a larger number of of infantry with tanks and small arms—that could directly affect events on the battlefield and a smaller number of intruder aircraft and crews that might modestly reduce the scale of Allied strategic air attacks. The Fernachtjagd had become a luxury in a time of want.

Politically, reliance on intruders was equally unsustainable in a long war. Once Allied air raids ceased to be a mere annoyance and began to ruin German cities and massacre their inhabitants, the country's political leadership could not simply defend the country: the regime had to be seen to defend the country. Bombers destroyed over East Anglia—or in remote Himmelbett boxes for that matter—did nothing to bolster public morale. Given the scarcity of twin-engined night fighters and crews, Germany's leadership had to choose between short-range home defence—which could be seene—and Fernachtjagd. The Fernachtjagd was an unjustifiable luxury in this instance as well.

After 1942, the Luftwaffe's long-range night fighter units were reallocated to more pressing, more conventional duties. Many were pulled back to the frontiers of the Reich and used as dedicated interceptors and ground attack aircraft. Others were assigned as long-range fighters over the Atlantic or for local, tactical support on the Mediterranean and Eastern fronts. Late in 1941, NJG II left Gilze-Rijen for Catania in Sicily, whence it supported the Italian German air assault on Malta and provided cover for Rommel's beleaguered supply convoys. Small detachments were soon scattered across the theater as immediate tactical necessity dictated, from the Bay of Biscay and the French Mediterranean coast in the north and west to Benghazi in the south and Crete in the east.

Given the economic and geographical realities facing Germany once Britain refused a separate peace and once the USA and USSR became belligerents, the reassignment of a few long-range intruders could not be expected to materially alter the outcome. Accordingly, in 1944, as the war situation worsened and Germany's inability to alter her situation by mass production and mass mobilization became increasingly clear,the potential efficiency of intruder tactics once again attracted notice, this time from a seemingly unlikely source, the then under-utilized Luftwaffe fast bomber formations in France, which had just converted to an aircraft that could be spared for intruder duties, having proved unsuitable and/or unpopular in other, higher-priority roles: the intended successor to the Bf110 Zerstorer, the Messerschmitt Me410.

The Me410 was an unfortunate airplane developed against a dated and over-demanding specification by too few engineers at a time when other projects were already taking priority. By the time it appeared in numbers, it was largely obsolete. The Me210, as the aircraft was first known, suffered from intractable handling difficulties that were solved only with time, testing, and major redesign. By the time a satisfactory version appeared as the Me410, it was too slow to survive as an unescorted day bomber or reconnaissance aircraft. While handling characteristics were acceptable, maneuverability was inadequate, even for a twin-engined fighter. The Me410 could not have held its own against Mosquitos and Beaufighters and its 1450-mi (2333-km) range was not outstanding, so it had few attractions in the maritime role. The Nachtjagd chose to soldier on with the Bf110G. As a heavy interceptor of unescorted day bombers, the Me410 was relatively successful for a while but still proved more vulnerable to the heavy defensive fire of American bomber formations than its single-engined counterparts. When long-range, single-engined American escort fighters appeared over the Reich in 1943, its usefulness in this role came to an abrupt end as well.

By 1943, however, the Dornier Do217, the mainstay of the Kampgeschwadern in the West, was proving too vulnerable for operations over the British Isles, even at night. Dorniers were valuable for antishipping and escort work over the Mediterranean and the Bay of Biscay and could not be thrown away in what were, by now, token propaganda missions. So, to sustain limited operations against the United Kingdom at minimum cost, V/KG 2 and elements of KG 51 converted to the Messerschmitt Me410A-1 and B-1 subtypes, which were configured as fast light bombers. The Me410 had a bomb bay that could hold a normal load of 1100 lbs (500 KG) and could reach a top speed of 388 mph (624 kph)—ideal for the campaign of high-speed, low-altitude nuisance bombing that would become known as the "Baby Blitz". Since the multirole Me410 design included a standard fighter-type, fixed, forward-firing armament of two 20-mm MG151 cannon and two 7.92-mm MG17 (Me410A) or 13-mm MG131 (Me410B) machine guns, the aircraft could also operate as an intruder. This latter role proved successful enough that, by 1944, V/KG2 and I and II/KG51 were operating many of their aircraft as dedicated Me410A-1/U-2 fighters, with an additional pair of 20-mm cannon installed in the bomb bay in a Waffenbehalter 151 weapon pod.

On the evening of 22 April 1944, a dozen or so Me410s from KG 51 followed bombers of the US Army Air Force 8th Air Force home from a raid against the railroad marshalling yards at Hamm in Germany. The Americans had despatched a mixed force of 803 B-17 and B-24 bombers against the target, accompanied by an escort of no less than 859 P-38,P-47, and P-51 fighters. Losses were relatively modest over enemy territory—eight B-17s and seven B-24s shot down with one B-17 and 14 B-24s damaged beyond repair, plus two P-38s, five P-47s and six P-51s lost and one P-38 damaged beyond repair. But, as the mission progressed, succeeding units seem to have had increasing difficulty locating the target. The B-17s went in first, and 459 of 526 found the target, while only one attacked an unidentified target of opportunity. But only 179 of the 2nd Air Division's 277 B-24 Liberators bombed the primary target, while 50 diverted to the secondary, Koblenz, and 36 attacked unidentified targets of opportunity. This seems to have disorganized the time table for the return flight and scattered the final USAAF formations. As dusk fell, the 389th and 458th Bomb Groups were still well short of their East Anglian bases, and KG51's Messerschmitts had successfully infiltrated their ranks, where the latter could not be detected by ground-based radar. The fighters attacked just as the B-24s were entering the landing pattern at about 2200 hours. Tracer was seen from the airfield control tower, so the alert was given immediately and the airfield blacked out. In the resulting melee, the Me410s shot down 12 B-24s in a matter of minutes. A B-24 waist gunner shot down Me410 9K+HP (werke number 420458) at Ashby St. Mary, and air gunners and/or airfield antiaircraft guns damaged 9K+MN (werke number 420314) severely enough that it never returned to its base in France. Many B-24s were damaged by friendly fire, as gunners fired wildly at half-seen aircraft in the gathering darkness.

By 1945, diminishing fuel reserves, heavy losses, rapidly contracting fronts, and Allied electronic countermeasures (ECM) severely restricted the effectiveness of the conventional Luftwaffe night fighter arm and forced a more determined return to intruder tactics. Noise jamming and mass deployment of windows and chaff (radar-reflecting strips of reinforced aluminum foil) had largely blinded German air and ground radars, while heavy communications-jamming crippled the ground-controlled fighter-direction system. Since twin-enigned aircraft lost much of their advantage under such conditions and were more vulnerable to the aggressive, radar-equipped Mosquito intruders that now accompanied RAF bomber streams, single-seat Wilde Sau fighters increasingly took on the nocturnal interception tasks once reserved for heavy Zerstorern. But the long range and navigational facilities offered by the mainstay of the conventional Nachtjagd, the Junkers Ju88G, could still be used to effect over Great Britain, where few Luftwaffe aircraft were expected to venture this late in the war.

In January, the German night fighters played a limited role during the Bodenplatte attacks on Allied forward airfields, serving as ground attack and pathfinder aircraft. This seems to have inspired a similar strike against RAF Bomber Command bases, Operation Gisela, the first and last attempt to mount a coordinated, mass intruder operation over the British Isles. On the night of March 3/4, 1945, with the Red Army on the outskirts of Berlin and the end of the war just weeks away, 142 Ju88G night fighters from I, II, and II/NJG 2, II and IV/NJG 3, III/NJG 4, and III/NJG 5 followed some 500 British heavy bombers home from a raid on the synthetic oil works at Kamen and the Dortmund-Ems canal. The night fighters skimmed the waves, relying on newly fitted radar altimeters, or mingled with the bomber stream to avoid detection by British early warning radar. At this late date, RAF aircrew were apparently becoming complacent and were remarkably lax once they crossed the English coast. Many turned on their navigation lights and left them on, even after being warned that intruders were a possibility. At least some of the intruding night fighters did likewise in the hopes of being mistaken for friendly aircraft. The result was pandemonium. Bomber Command bases across Yorkshire turned off their lights and closed their runways, leaving panicky aircrew to mill about for some two hours while searching for alternate landing fields. While only nine aircraft had been lost over the Continent that night, nineteen were shot down over Driffield, Dishforth, Brafferton, Elvington, Sutton-on-Derwent, and Knaresboroug. These included:

- eight Halifaxes of 4 Group

- two Lancasters of 5 Group

- three Halifaxes, one Fortress, and one Mosquito of 100 Group*

- 2 Lancasters and 2 Halifaxes from Heavy Conversion Units**

Heavy as RAF losses were, German losses were worse: 25 Ju88s. At least three intruders collided with the ground during low-level strafing runs. The remainder fell to the guns of the Mosquito night fighters that eventually swarmed to the scene. While many commentators have argued over the years that earlier adoption of Gisela-style tactics might have crippled the RAF's strategic bombing campaign, the mission was a clearly such a disaster for the Luftwaffe that Gisela would not and could not have been repeated. Even a healthier air arm than the Luftwaffe could not sustain over 12% losses per operation for any length of time. The Nachtjagd was never large to begin with—it mustered perhaps 600-700 aircraft at its height, of which some 350 were long-range Ju88s. Heavy losses during Bodenplatte and subsequent nocturnal ground attack sorties significantly reduced its numbers below these figures. All but continuous, day and night attacks by Allied fighters and fighter bombers (including Firebash nocturnal napalm strikes on Luftwaffe airfields) exacted an additional toll. These losses, combined with fuel shortages and the rapid approach of the front lines made any repeat of Gisela impossible. Moreover, what success Gisela achieved was due largely to the long absence of enemy intruders over Britain. Had such operations been more common, it is likely that the RAF would have been less complacent and less slow to react. The bombers might have suffered less severely, while the attackers might have suffered more grievously than they did, given the technical ascendency of the RAF night-fighting arm at that time.

As it was, the Luftwaffe managed to mount only a few small-scale intruder operations in March and April 1945. The Nachtjagd was by then a spent force, and Gisela was, effectively, the last notable operation by a German night fighter arm that would disintegrate in a mere matter of weeks, as its personnel were drafted and sent piecemeal into pointless skirmishes or allowed to slip away quietly and return home to await the inevitable.

IvanDrago-33

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 15 October 2021

- Messages

- 1

- Reaction score

- 0

Good day, guys ! Can you, please, tell me where I can find ALL readable stencils for Messerschmitt Me-210/410? Thank you in advance for your reply. Best regards to you

Ivan Culjak

ACCESS: Confidential

- Joined

- 11 September 2021

- Messages

- 53

- Reaction score

- 53

It could be a good answer, but it's a mix of two completely different things. One is Me210/410 itself, itsIn my opinion, the real reason for abandoning formal intruder operations was practical: cost/benefit ratio. For example, a dozen Me410s of KG51 carried out a successful, impromptu intruder attack on USAAF B-24s returning from Hamm in 1944 (see below) and destroyed 12 out of the 1662 USAAF despatched at the cost of two Me410s: a rate of loss to intruders of about 0.7% for the USAAF vs a 17% loss rate for the Luftwaffe. The latter is simply not sustainable, especially when the US could replace pilots and aircraft and Germany could not.

I'm attaching part of an assessment that I wrote for Chandelle (text and illustrations © 2007-2008 by Robert Craig Johnson. All rights reserved):

"For all the success of the intruder tactic, Luftwaffe adoption of intruder tactics was limited by the exigencies of supply and political necessity. The Himmelbet system was successful in large part because it, for the most part, did not compete for aircraft and aircrew with better established arms of the service. The Messerschmidt Bf110 was thus entirely adequate. But the intruder role required an aircraft and crew capable of locating a point at a considerable distance from home and then operating for an extended period over hostile territory. An altogether larger, bomber-sized aircraft with a highly trained, bomber-type crew was thus essential.

"As it happened,frontline demand for aircraft and skilled aviators far outstripped Germany's ability to produce either in wartime. For all its initial successes, Germany was, relative to its opponents, a fairly small and under-industrialized country with few natural resources and a modest population. It counted on a short war, in which scarcities and wastage could be made up quickly using captured enemy equipment and supplies. The Luftwaffe training organization was dwarfed by its counterparts in the British Commonwealth and the United States. It depended in large part on obsolete or captured French, Czech, and Dutch aircraft and engines for its equipment. When hopes for a short war and an advantageous peace began to evaporate, a tactic that concentrated scarce airframe materials, engines, and trained crews in a few sophisticated, long-range aircraft could not be sustained. As the frontlines began to constrict around Germany, the choice had to be made between a larger, less intensively trained force of fighter pilots and single-seat fighter-bombers—or a larger number of of infantry with tanks and small arms—that could directly affect events on the battlefield and a smaller number of intruder aircraft and crews that might modestly reduce the scale of Allied strategic air attacks. The Fernachtjagd had become a luxury in a time of want.

Politically, reliance on intruders was equally unsustainable in a long war. Once Allied air raids ceased to be a mere annoyance and began to ruin German cities and massacre their inhabitants, the country's political leadership could not simply defend the country: the regime had to be seen to defend the country. Bombers destroyed over East Anglia—or in remote Himmelbett boxes for that matter—did nothing to bolster public morale. Given the scarcity of twin-engined night fighters and crews, Germany's leadership had to choose between short-range home defence—which could be seene—and Fernachtjagd. The Fernachtjagd was an unjustifiable luxury in this instance as well.

After 1942, the Luftwaffe's long-range night fighter units were reallocated to more pressing, more conventional duties. Many were pulled back to the frontiers of the Reich and used as dedicated interceptors and ground attack aircraft. Others were assigned as long-range fighters over the Atlantic or for local, tactical support on the Mediterranean and Eastern fronts. Late in 1941, NJG II left Gilze-Rijen for Catania in Sicily, whence it supported the Italian German air assault on Malta and provided cover for Rommel's beleaguered supply convoys. Small detachments were soon scattered across the theater as immediate tactical necessity dictated, from the Bay of Biscay and the French Mediterranean coast in the north and west to Benghazi in the south and Crete in the east.

Given the economic and geographical realities facing Germany once Britain refused a separate peace and once the USA and USSR became belligerents, the reassignment of a few long-range intruders could not be expected to materially alter the outcome. Accordingly, in 1944, as the war situation worsened and Germany's inability to alter her situation by mass production and mass mobilization became increasingly clear,the potential efficiency of intruder tactics once again attracted notice, this time from a seemingly unlikely source, the then under-utilized Luftwaffe fast bomber formations in France, which had just converted to an aircraft that could be spared for intruder duties, having proved unsuitable and/or unpopular in other, higher-priority roles: the intended successor to the Bf110 Zerstorer, the Messerschmitt Me410.

The Me410 was an unfortunate airplane developed against a dated and over-demanding specification by too few engineers at a time when other projects were already taking priority. By the time it appeared in numbers, it was largely obsolete. The Me210, as the aircraft was first known, suffered from intractable handling difficulties that were solved only with time, testing, and major redesign. By the time a satisfactory version appeared as the Me410, it was too slow to survive as an unescorted day bomber or reconnaissance aircraft. While handling characteristics were acceptable, maneuverability was inadequate, even for a twin-engined fighter. The Me410 could not have held its own against Mosquitos and Beaufighters and its 1450-mi (2333-km) range was not outstanding, so it had few attractions in the maritime role. The Nachtjagd chose to soldier on with the Bf110G. As a heavy interceptor of unescorted day bombers, the Me410 was relatively successful for a while but still proved more vulnerable to the heavy defensive fire of American bomber formations than its single-engined counterparts. When long-range, single-engined American escort fighters appeared over the Reich in 1943, its usefulness in this role came to an abrupt end as well.

By 1943, however, the Dornier Do217, the mainstay of the Kampgeschwadern in the West, was proving too vulnerable for operations over the British Isles, even at night. Dorniers were valuable for antishipping and escort work over the Mediterranean and the Bay of Biscay and could not be thrown away in what were, by now, token propaganda missions. So, to sustain limited operations against the United Kingdom at minimum cost, V/KG 2 and elements of KG 51 converted to the Messerschmitt Me410A-1 and B-1 subtypes, which were configured as fast light bombers. The Me410 had a bomb bay that could hold a normal load of 1100 lbs (500 KG) and could reach a top speed of 388 mph (624 kph)—ideal for the campaign of high-speed, low-altitude nuisance bombing that would become known as the "Baby Blitz". Since the multirole Me410 design included a standard fighter-type, fixed, forward-firing armament of two 20-mm MG151 cannon and two 7.92-mm MG17 (Me410A) or 13-mm MG131 (Me410B) machine guns, the aircraft could also operate as an intruder. This latter role proved successful enough that, by 1944, V/KG2 and I and II/KG51 were operating many of their aircraft as dedicated Me410A-1/U-2 fighters, with an additional pair of 20-mm cannon installed in the bomb bay in a Waffenbehalter 151 weapon pod.

On the evening of 22 April 1944, a dozen or so Me410s from KG 51 followed bombers of the US Army Air Force 8th Air Force home from a raid against the railroad marshalling yards at Hamm in Germany. The Americans had despatched a mixed force of 803 B-17 and B-24 bombers against the target, accompanied by an escort of no less than 859 P-38,P-47, and P-51 fighters. Losses were relatively modest over enemy territory—eight B-17s and seven B-24s shot down with one B-17 and 14 B-24s damaged beyond repair, plus two P-38s, five P-47s and six P-51s lost and one P-38 damaged beyond repair. But, as the mission progressed, succeeding units seem to have had increasing difficulty locating the target. The B-17s went in first, and 459 of 526 found the target, while only one attacked an unidentified target of opportunity. But only 179 of the 2nd Air Division's 277 B-24 Liberators bombed the primary target, while 50 diverted to the secondary, Koblenz, and 36 attacked unidentified targets of opportunity. This seems to have disorganized the time table for the return flight and scattered the final USAAF formations. As dusk fell, the 389th and 458th Bomb Groups were still well short of their East Anglian bases, and KG51's Messerschmitts had successfully infiltrated their ranks, where the latter could not be detected by ground-based radar. The fighters attacked just as the B-24s were entering the landing pattern at about 2200 hours. Tracer was seen from the airfield control tower, so the alert was given immediately and the airfield blacked out. In the resulting melee, the Me410s shot down 12 B-24s in a matter of minutes. A B-24 waist gunner shot down Me410 9K+HP (werke number 420458) at Ashby St. Mary, and air gunners and/or airfield antiaircraft guns damaged 9K+MN (werke number 420314) severely enough that it never returned to its base in France. Many B-24s were damaged by friendly fire, as gunners fired wildly at half-seen aircraft in the gathering darkness.

By 1945, diminishing fuel reserves, heavy losses, rapidly contracting fronts, and Allied electronic countermeasures (ECM) severely restricted the effectiveness of the conventional Luftwaffe night fighter arm and forced a more determined return to intruder tactics. Noise jamming and mass deployment of windows and chaff (radar-reflecting strips of reinforced aluminum foil) had largely blinded German air and ground radars, while heavy communications-jamming crippled the ground-controlled fighter-direction system. Since twin-enigned aircraft lost much of their advantage under such conditions and were more vulnerable to the aggressive, radar-equipped Mosquito intruders that now accompanied RAF bomber streams, single-seat Wilde Sau fighters increasingly took on the nocturnal interception tasks once reserved for heavy Zerstorern. But the long range and navigational facilities offered by the mainstay of the conventional Nachtjagd, the Junkers Ju88G, could still be used to effect over Great Britain, where few Luftwaffe aircraft were expected to venture this late in the war.

In January, the German night fighters played a limited role during the Bodenplatte attacks on Allied forward airfields, serving as ground attack and pathfinder aircraft. This seems to have inspired a similar strike against RAF Bomber Command bases, Operation Gisela, the first and last attempt to mount a coordinated, mass intruder operation over the British Isles. On the night of March 3/4, 1945, with the Red Army on the outskirts of Berlin and the end of the war just weeks away, 142 Ju88G night fighters from I, II, and II/NJG 2, II and IV/NJG 3, III/NJG 4, and III/NJG 5 followed some 500 British heavy bombers home from a raid on the synthetic oil works at Kamen and the Dortmund-Ems canal. The night fighters skimmed the waves, relying on newly fitted radar altimeters, or mingled with the bomber stream to avoid detection by British early warning radar. At this late date, RAF aircrew were apparently becoming complacent and were remarkably lax once they crossed the English coast. Many turned on their navigation lights and left them on, even after being warned that intruders were a possibility. At least some of the intruding night fighters did likewise in the hopes of being mistaken for friendly aircraft. The result was pandemonium. Bomber Command bases across Yorkshire turned off their lights and closed their runways, leaving panicky aircrew to mill about for some two hours while searching for alternate landing fields. While only nine aircraft had been lost over the Continent that night, nineteen were shot down over Driffield, Dishforth, Brafferton, Elvington, Sutton-on-Derwent, and Knaresboroug. These included:

Both the most experienced and least experienced formations suffered losses. 100 (Bomber Support) Group was the RAF's elite electronic countermeasures and offensive night-fighting unit. The Heavy Conversion Units were primarily training formations that had merely mounted diversionary attacks in support of the main force. Five additional training aircraft were shot down or lost to accidents while engaged in routine, local night-flying training.

- eight Halifaxes of 4 Group

- two Lancasters of 5 Group

- three Halifaxes, one Fortress, and one Mosquito of 100 Group*

- 2 Lancasters and 2 Halifaxes from Heavy Conversion Units**

Heavy as RAF losses were, German losses were worse: 25 Ju88s. At least three intruders collided with the ground during low-level strafing runs. The remainder fell to the guns of the Mosquito night fighters that eventually swarmed to the scene. While many commentators have argued over the years that earlier adoption of Gisela-style tactics might have crippled the RAF's strategic bombing campaign, the mission was a clearly such a disaster for the Luftwaffe that Gisela would not and could not have been repeated. Even a healthier air arm than the Luftwaffe could not sustain over 12% losses per operation for any length of time. The Nachtjagd was never large to begin with—it mustered perhaps 600-700 aircraft at its height, of which some 350 were long-range Ju88s. Heavy losses during Bodenplatte and subsequent nocturnal ground attack sorties significantly reduced its numbers below these figures. All but continuous, day and night attacks by Allied fighters and fighter bombers (including Firebash nocturnal napalm strikes on Luftwaffe airfields) exacted an additional toll. These losses, combined with fuel shortages and the rapid approach of the front lines made any repeat of Gisela impossible. Moreover, what success Gisela achieved was due largely to the long absence of enemy intruders over Britain. Had such operations been more common, it is likely that the RAF would have been less complacent and less slow to react. The bombers might have suffered less severely, while the attackers might have suffered more grievously than they did, given the technical ascendency of the RAF night-fighting arm at that time.

As it was, the Luftwaffe managed to mount only a few small-scale intruder operations in March and April 1945. The Nachtjagd was by then a spent force, and Gisela was, effectively, the last notable operation by a German night fighter arm that would disintegrate in a mere matter of weeks, as its personnel were drafted and sent piecemeal into pointless skirmishes or allowed to slip away quietly and return home to await the inevitable.

technical merits and this should be a main object of interest of this topic.

A military situation of Germany and consequently, the war contribution of Me210/410, Bodenplatte, that's not a theme of secret aicraft forum, at least IMHO.

So my question is how get Me410 obsolete before even flying, as you said? What was technically so wrong with it - comparing to other contemporary aicraft.. How the others get it better ...could it be Mosquito , or...

Last edited:

It could be a good answer, but it's a mix of two completely different things. One is Me210/410 itself, its

technical merits and this should be a main object of interest of this topic.

A military situation of Germany and consequently, the war contribution of Me210/410, Bodenplatte, that's not a theme of secret aicraft forum, at least IMHO.

So my question is how get Me410 obsolete before even flying, as you said? What was technically so wrong with it - comparing to other contemporary aicraft.. How the others get it better ...could it be Mosquito , or...

The wing of the Me 210 was - against the will of Messerschmitt and because of an order of the RLM - designed by Arado (and not Messerschmitt) engineers which led to the inadequate flying characterisics of the 210. The correction and the political hickhack between Messerschmitt, Milch, etc. also contributed to a lot of wasted time as well as the reconstruction of a new wing. By the time the 410 was ready, the more agile US escort fighters began to dominate the sky which accelerated the decline of the 410. But certainly forum members like Dan or Calum have a more detailed analysis.

scorpiodude

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 23 June 2022

- Messages

- 11

- Reaction score

- 15

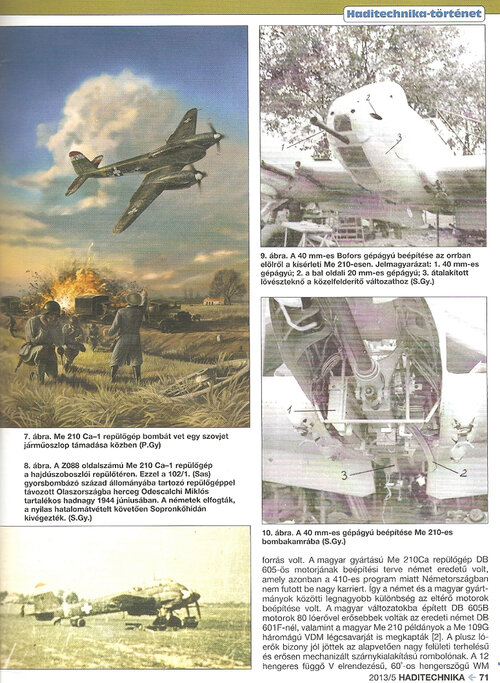

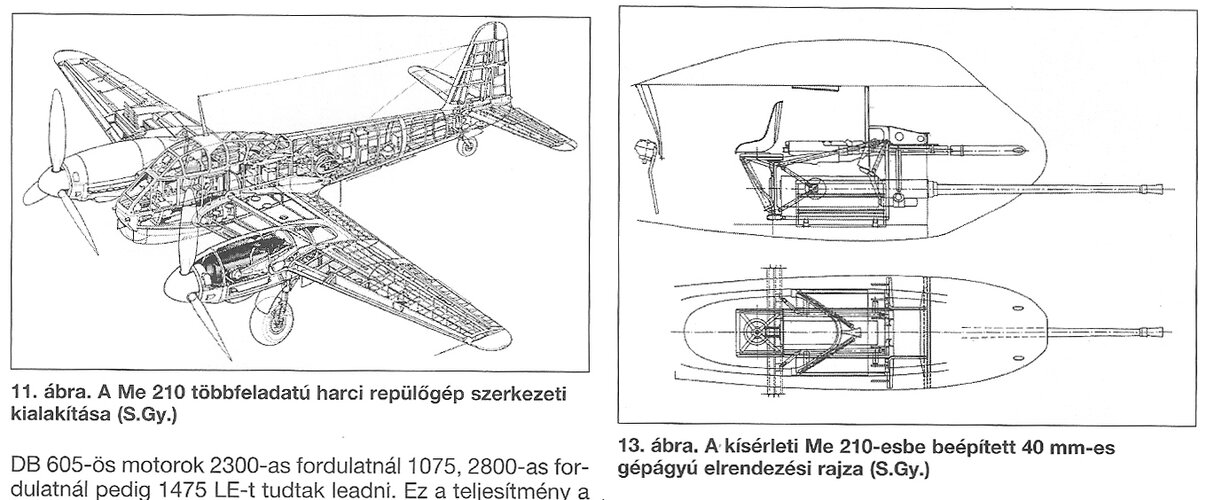

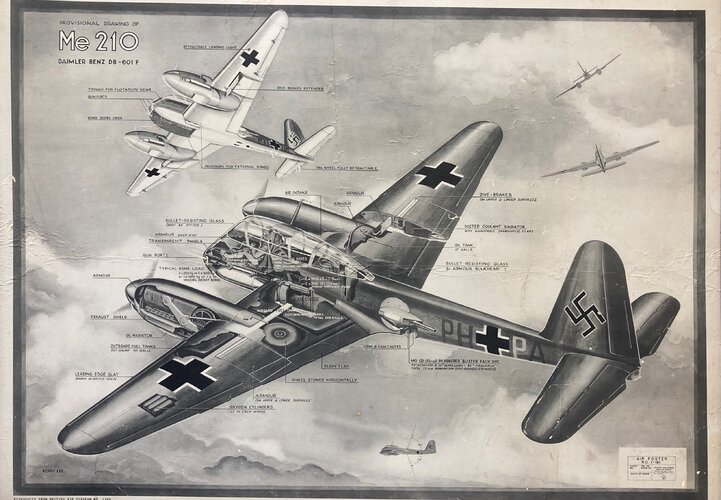

Although the Me-210 was mostly a failure in German service it was licensed to Hungary where work was done to turn it into the somewhat successful Me-210Ca-1. These changes included a lengthened tail, new wings swept back by 4 degrees, as well as DB605 engines and the removal of most of the armor. One of the intended roles for this new heavy fighter was to encounter bombers from outside the effective range of their tail guns. The ability to fit 15cm nebelwerfer rockets was thus included and to increase firepower even more a 40mm bofors 39M cannon was able to be fitted into the front bomb bay. Loading of the 40mm was the responsibility of the radio operator. The factory was stopped before mass production of the 40mm armament could start. Overall, these changes brought the Me-210 up to a similar level to the Me-410 which enjoyed some limited success.

Attachments

I disagree. Engineering has to be judged against the requirements, which are defined by anticpated and, later, actual usage. The military situation is thus the main standard against which a design has to be measured.It could be a good answer, but it's a mix of two completely different things. One is Me210/410 itself, its

technical merits and this should be a main object of interest of this topic.

A military situation of Germany and consequently, the war contribution of Me210/410, Bodenplatte, that's not a theme of secret aicraft forum, at least IMHO.

The Me410 took a long time to develop. But it eventually seems to have been a decent airplane--just an airplane that was not needed, could not be successful at the time it was put into production, and consumed resources that could have been better used by necessary projects.

The Me410 was designed and engineered primarily as a heavy, day fighter, capable of operating unescorted over distant targets and of destroying unescorted but heavily armed bombers over the Reich--a 1930s requirement. Heavy forward firing armament and a sophisticated, heavy, and complex, remotely operated defensive rear armament were supposed to be enough to insure its survival against light, single-engined interceptors. Over the Reich, only bombers and, perhaps, other twin-engined escort fighters were expected to appear.

These assumptions were known to be wrong by the time the Me410 was ready. Twin-engined fighters were easy targets for single-engined fighters, which appeared over the Reih as well as over enemy territory.

Twin-engined, radar-equipped night fighters were needed--desperately. But this was the one role for which the Me410 design was completely unsuited. Instead, the obsolescent Bf110G had to be kept in production and, indeed, scheduled for replacement by the Bf110H.

The Me410 was a reasonable light-bomber, but not good enough to operate in daylight against enemy fighters. It operated over the British Isles during hit-and-run night r aids. But even then, it's bomb load was no greater than that of the single-engined Fw190 fighter-bombers that participated alongside it--and the latter could be used in daylight because they could defend themselves.

So despite whatever qualities it might have had, the Me410 was a bad design.

Hi Basil,

Do you have more details on that? From Kosin, "Die Entwicklung der deutschen Jagdflugzeuge", it looks as if Walter Rethel was the chief designer for the Me 210, but if I understand the situation correctly, he had left his previous job with Arado to join Messerschmitt instead.

Regards,

Henning (HoHun)

The wing of the Me 210 was - against the will of Messerschmitt and because of an order of the RLM - designed by Arado (and not Messerschmitt) engineers which led to the inadequate flying characterisics of the 210.

Do you have more details on that? From Kosin, "Die Entwicklung der deutschen Jagdflugzeuge", it looks as if Walter Rethel was the chief designer for the Me 210, but if I understand the situation correctly, he had left his previous job with Arado to join Messerschmitt instead.

Regards,

Henning (HoHun)

Ivan Culjak

ACCESS: Confidential

- Joined

- 11 September 2021

- Messages

- 53

- Reaction score

- 53

If German aviation designs are to be judged by German military situation, then there is no successful German aviation design, at all. But ok, let agree to disagree....I disagree. Engineering has to be judged against the requirements, which are defined by anticpated and, later, actual usage. The military situation is thus the main standard against which a design has to be measured.

Last edited:

Hi Iverson,

Actually, requirements usually are defined explicitely in terms of specified features or parameters. "Usage" would be the role, which in the requirements shows up as appropriate specific definitions of performance parameters, such as speed or range, or as features, such as combat equipment.

The industry built aircraft to specifications, it was the customers who defined the specifications in such a way that the resulting aircraft would meet their needs.

Regards,

Henning (HoHun)

Engineering has to be judged against the requirements, which are defined by anticpated and, later, actual usage.

Actually, requirements usually are defined explicitely in terms of specified features or parameters. "Usage" would be the role, which in the requirements shows up as appropriate specific definitions of performance parameters, such as speed or range, or as features, such as combat equipment.

The industry built aircraft to specifications, it was the customers who defined the specifications in such a way that the resulting aircraft would meet their needs.

Regards,

Henning (HoHun)

I have this info from Calum Douglas' excellent book "The Secret Horsepower Race", page 350. It is mentioned that two Arado designers - Rethel and Fröhlich - were inserted into the team by the RLM.Hi Basil,

Do you have more details on that? From Kosin, "Die Entwicklung der deutschen Jagdflugzeuge", it looks as if Walter Rethel was the chief designer for the Me 210, but if I understand the situation correctly, he had left his previous job with Arado to join Messerschmitt instead.

Regards,

Henning (HoHun)

Hi Basil,

Thanks a lot for the precise reference!

Looking up Calum's footnote, the text quoted there actually reads slightly differently ... not sure what undertones "at the instigation of the RLM" might have to a native speaker, but the thing the RLM insisted on was skipping the step of passing the design through the manufacturing office.

I am not sure that all this means that Messerschmitt was forced to hand over design of the Me 210 to the (former) Arado engineers against his will ... I could imagine that he requested additional engineering capacity from the RLM, and was assigned these Rethel, Fröhlich and (from Calum's footnote) possibly even more engineers. Still a bit surprising, since the RLM at the same time also ordered a competing destroyer design from Arado - normally, engineers were re-assigned only when a company didn't have worthwhile projects for them.

What the RLM seems to have enforced, according to the quote, was the bypassing of the manufacturing office. Not sure what that implies specifically, but as the RLM as a general policy tried to take shortcuts when getting new types into service (not so successfully, if one believes Lusser or Eisenlohr), that would fit the overall picture.

Regards,

Henning (HoHun)

I have this info from Calum Douglas' excellent book "The Secret Horsepower Race", page 350. It is mentioned that two Arado designers - Rethel and Fröhlich - were inserted into the team by the RLM.

Thanks a lot for the precise reference!

Looking up Calum's footnote, the text quoted there actually reads slightly differently ... not sure what undertones "at the instigation of the RLM" might have to a native speaker, but the thing the RLM insisted on was skipping the step of passing the design through the manufacturing office.

I am not sure that all this means that Messerschmitt was forced to hand over design of the Me 210 to the (former) Arado engineers against his will ... I could imagine that he requested additional engineering capacity from the RLM, and was assigned these Rethel, Fröhlich and (from Calum's footnote) possibly even more engineers. Still a bit surprising, since the RLM at the same time also ordered a competing destroyer design from Arado - normally, engineers were re-assigned only when a company didn't have worthwhile projects for them.

What the RLM seems to have enforced, according to the quote, was the bypassing of the manufacturing office. Not sure what that implies specifically, but as the RLM as a general policy tried to take shortcuts when getting new types into service (not so successfully, if one believes Lusser or Eisenlohr), that would fit the overall picture.

Regards,

Henning (HoHun)

You are right; it is not totally conclusive.Hi Basil,

Thanks a lot for the precise reference!

Looking up Calum's footnote, the text quoted there actually reads slightly differently ... not sure what undertones "at the instigation of the RLM" might have to a native speaker, but the thing the RLM insisted on was skipping the step of passing the design through the manufacturing office.

I am not sure that all this means that Messerschmitt was forced to hand over design of the Me 210 to the (former) Arado engineers against his will ... I could imagine that he requested additional engineering capacity from the RLM, and was assigned these Rethel, Fröhlich and (from Calum's footnote) possibly even more engineers. Still a bit surprising, since the RLM at the same time also ordered a competing destroyer design from Arado - normally, engineers were re-assigned only when a company didn't have worthwhile projects for them.

What the RLM seems to have enforced, according to the quote, was the bypassing of the manufacturing office. Not sure what that implies specifically, but as the RLM as a general policy tried to take shortcuts when getting new types into service (not so successfully, if one believes Lusser or Eisenlohr), that would fit the overall picture.

Regards,

Henning (HoHun)

- Joined

- 29 July 2009

- Messages

- 1,769

- Reaction score

- 2,476

- Joined

- 26 May 2006

- Messages

- 34,901

- Reaction score

- 15,761

In Wikipedia,they spoke about Me.510,was it a real design ?.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

List of RLM aircraft designations - Wikipedia

- Joined

- 3 June 2006

- Messages

- 3,094

- Reaction score

- 3,964

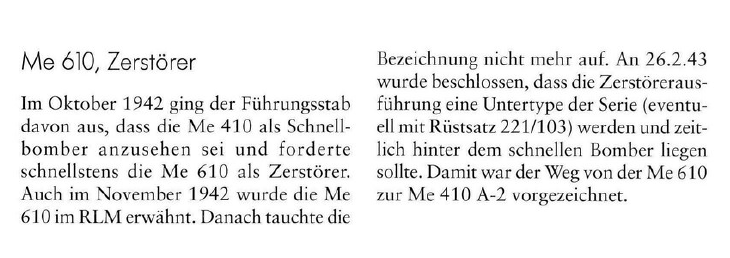

IIRC, the Messerschmitt "Me 510" and "Me 610" were only used at the RLM to differentiate the distinct roles (i.e. Schnellbomber, Zerstörer,In Wikipedia,they spoke about Me.510,was it a real design ?.

List of RLM aircraft designations - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

or night fighter) over the basic Messerschmitt Me 410. Messerschmitt kept Me 410, but differentiate the subtypes with letters and Umrüst-Bausätze (factory conversion kits). For example, the "Me 610" was really the planned Me 410 A-2.

My source: Mankau, Heinz; Petrick, Peter - Messerschmitt Bf 110, Me 210, Me 410 - Aviatic Verlag 2001

Hi,

Do you happen to have the page numbers? I didn't manage to find the Me 510 designation when I was just looking for it shortly before you posted.

Regards,

Henning (HoHun)

IIRC, the Messerschmitt "Me 510" and "Me 610" were only used at the RLM to differentiate the distinct roles (i.e. Schnellbomber, Zerstörer,

or night fighter) over the basic Messerschmitt Me 410. Messerschmitt kept Me 410, but differentiate the subtypes with letters and Umrüst-Bausätze (factory conversion kits). For example, the "Me 610" was really the planned Me 410 A-2.

Do you happen to have the page numbers? I didn't manage to find the Me 510 designation when I was just looking for it shortly before you posted.

Regards,

Henning (HoHun)

- Joined

- 26 May 2006

- Messages

- 34,901

- Reaction score

- 15,761

IIRC, the Messerschmitt "Me 510" and "Me 610" were only used at the RLM to differentiate the distinct roles (i.e. Schnellbomber, Zerstörer,

or night fighter) over the basic Messerschmitt Me 410. Messerschmitt kept Me 410, but differentiate the subtypes with letters and Umrüst-Bausätze (factory conversion kits). For example, the "Me 610" was really the planned Me 410 A-2.

My source: Mankau, Heinz; Petrick, Peter - Messerschmitt Bf 110, Me 210, Me 410 - Aviatic Verlag 2001

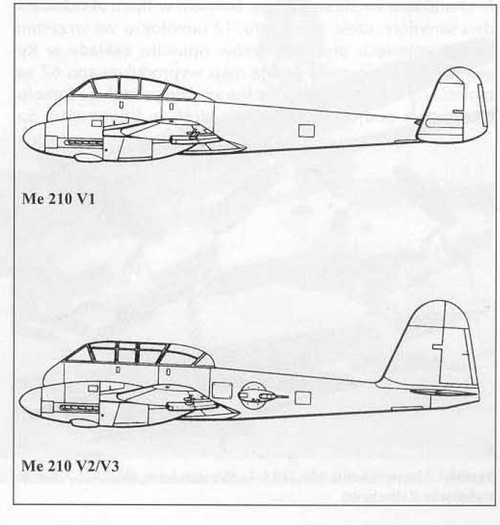

From the same source.

Attachments

Similar threads

-

-

Questions about two Germany competitions and projects

- Started by hesham

- Replies: 16

-

-

-

Merlin-engined Messerschmitt Bf 109 project 1941 - document conundrum

- Started by newsdeskdan

- Replies: 62