[Harry] Atwood brought Higgins the latest generation of his woven plastic-plywood. Higgins was impressed. The entire log could be used, and they could use locally grown Southern wood, bypassing wartime shortages. Atwood had also brought Higgins his plans for a 150-ton, ten-engine flying wing with a three-hundred-foot wingspan. (One-third larger than a 747's wingspan.) Atwood had revived his flying wing dreams from his Monson days, and presented it as the solution for flying cargo. A flying wing just looks good, a “pure” airplane; the stretch of wing is what we respond to when we see a soaring hawk or a seabird. Higgins took up the cause: “I shall build planes without outside privies on them," he said.

Airplanes are the future of cargo, said the shipbuilder. “I much prefer being in the air cargo carrier business to building surface carriers, because the airships are so much less vulnerable."

He set up Atwood and Bellanca and a staff of engineers in a mansion on a lake (...) Higgins had housed his other research geniuses in mansions around New Orleans, all reportedly under guard.

The Atwood-Bellanca project was separate from Higgins's other aviation business, a “super secret off-shoot devoted exclusively to research and experimenting. Atwood has developed a sensational kind of woven plywood and an even more sensational cargo plane design. Both are cloaked in secrecy,” wrote one aviation magazine. “Remember this,” said a company vice-president, “Mr. Higgins is in aviation for keeps.”

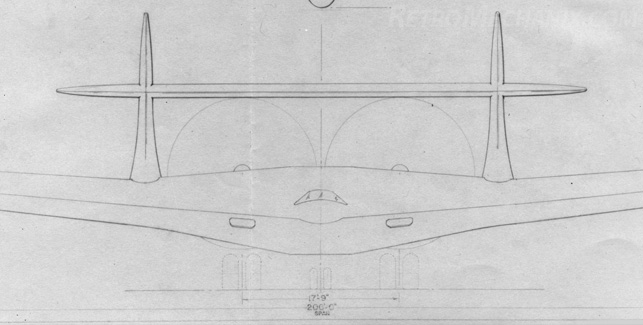

They were at work on the Higgins Air Freighter. The cargo would be carried inside the wing. As the design evolved, it was no longer a pure flying wing. One slightly smaller version had eight engines on the leading edge of a 240-foot wingspan, with a twin, 80-foot long tailboom supporting a horizontal stabilizer. For its day, it was a Paul Bunyan-sized airplane, about double the size of the B-29, then the largest plane flying.

Two wartime shortages and the politics of a cancelled contract had made this outsized dream seem attainable. There was an urgent need for air transport planes. “Not a single plane originally conceived for cargo is in service in the Western Hemisphere,” reported the Office of War Information in June 1943. (...) “At present American air transport needs are being filled by operations that show considerable ingenuity but which cannot be called eflicient,” said the Office of War Information.

The War Production Board called on the army to double cargo plane production. The head of the army’s air forces, Lt. General "Hap" Arnold, said the cargo planes should be built of “noncritical materials.” Steel, aluminum, and other metals were in short supply. Wood was in fashion again for airplanes.

(...)

In 1942 Higgins gained and lost the largest ship contract in American history. (...) He was building a two-mile-long floating assembly line for ships, the world’s first. A ship would be built in 5 days, instead of the usual 150 days. One ship a day would come off the line, a rate that would match the country's entire ship production. “It can't be done,“ said other shipbuilders. “The hell it can't,” said Higgins.

Four months later, the contract was abruptly cancelled. Higgins had spent ten million dollars blasting and dredging twelve hundred acres of swamp for the factory where upwards of sixty thousand workers would build the ships. The steel shortage had worsened; there was not enough steel to build the factory, let alone the ships. Other shipyards had cut back, some Detroit assembly lines had shut down, and armament production was threatened.

Higgins (...) made so much noise that President Roosevelt came to visit, the only Louisiana stop on his cross-country tour. Roosevelt had been secretary of the navy and knew Higgins, and recently Higgins had stood up at one of Eleanor Roosevelt's rallies and pledged to hire Negroes at equal pay (for which he was criticized). Roosevelt toured the plant for an hour, and invited Higgins to Washington. The uncompleted shipyard would be put to use.

For five weeks, Higgins and Atwood met with the president, the War Production Board, and army officials, including Atwood's old friend Hap Arnold. They displayed a three-foot model of the Higgins Air Freighter, and outlined their plan to build it with Atwood's woven plywood, which contained metal. “l call it a wood alloy,” said Higgins, adding apologetically, “I had to coin a name for it which is not very good, but the best l could do.” It was twice as strong as duraluminum of the same thickness, he said, but it was made primarily from noncritical materials. The Air Freighter‘s construction would make it virtually unsinkable, should it be forced down in the ocean, he said.

He wanted to build an untested type of airplane at a colossal scale with a new, untested material. The army was wary. “Mr. Higgins' proposal to build his planes of plywood—an unprecedented use of such material in planes of the contemplated size—aroused a storm of controversy,” said the New York Times. “It was pointed out, however, that the Russians had built their best fighters, the MIG-3, out of plywood. The British have also used plywood in a combat plane known as the Mosquito.”

Kaiser was already building a huge cargo plane, and there were many critics who said the plane would not be ready in time. The army needed production.

Higgins left Washington with a contract for twelve-hundred cargo planes of a conventional design [the Curtiss C-76 Caravan], to be built with Atwood's “wood alloy.” The two-hundred-million-dollar contract was larger than all the rest of his business, and one of the largest airplane contracts in American history. He would have to hire fifty to sixty thousand workers—80 percent women and 50 percent Negro, he said—and build a factory large enough to house a dozen football fields and a half dozen baseball fields.

He had not given up on the Air Freighter. He would build a demonstration plane with his own money. He had done that with the landing boats, and now they were in use all over the world. He would do it again with the great flying wing.

(...)

There was a big party at the Willard Hotel in Washington in a ballroom hung with model airplanes. Army brass and various wartime commissioners and congressmen toasted the success of Higgins. He'd show them how to build cargo planes in a hurry.

But he never got the chance. Higgins built his large assembly factory, set up Preston Tucker in a factory to build engines, and built a plywood sawmill, veneer mill, veneer plywood and molding plant, and a “wood alloy structures plant.”

A month before the airplane factory was completed, the contract for the Curtiss C-76 was cancelled. There were problems up the line. Higgins was a subcontractor, and, unfortunately, he had been yoked to a disaster.