- Joined

- 25 June 2014

- Messages

- 1,564

- Reaction score

- 1,499

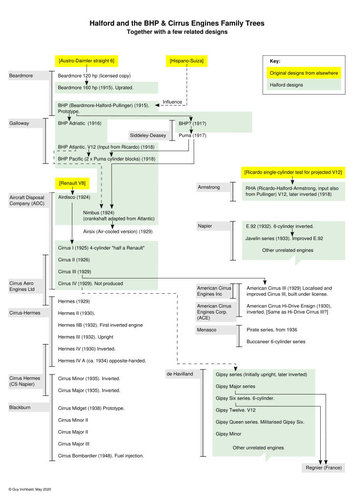

The ADC Cirrus was the first reliable and affordable aero engine and together with the de Havilland Moth, in the mid-1920s it created the golden age of private flying. It was also the first of the mass-produced small air-cooled four-cylinder inline light aircraft engines. And it has a curious, intriguing and only patchily-known history, its developed variants embracing a staggering quarter of a century in production and at least six manufacturers.

Aircraft Disposal Company (ADC)

Geoffrey de Havilland was mulling over what would become the Moth and realised that there was no suitable engine available: it had to be around 60-80 hp, but lighter and more reliable than the old workhorses. Meanwhile Major Frank Halford had revamped the old Renault V8 engine for the Aircraft Disposal Company, who had acquired hundreds if not thousands of them as WWI surplus. Its power doubled, it was being sold as the Airdisco. De Havilland had the bright idea of taking half the Renault and performing a similar miracle on it to create a four-cylinder inline. Halford took some persuading, and the result was the ADC Cirrus. The DH.60 Cirrus Moth launched it into the skies and into history. Developed variants the Cirrus II and III soon followed.

American Cirrus Engines Inc.

With the appearance of the III in 1929, American Cirrus Engines Inc. was set up to license-manufacture its own improved Cirrus III for the US market.

Cirrus Aero Engines Ltd

Presently de Havilland asked Halford to develop a more modern equivalent from scratch, which would become the Gipsy series. The engine designer had already severed his relationship with ADC, who were beginning to run out of the old Renaults and so Cirrus Aero Engines Ltd was formed, operating from the same address as ADC but without Halford, to start manufacturing the Cirrus range from scratch. They launched the improved Cirrus Hermes in 1929.

Cirrus-Hermes Engineering Company Limited

In 1931 the Cirrus-Hermes Engineering Company Limited was set up at Croydon, where they further developed the Cirrus-Hermes II and III. They next turned the Hermes II upside down as the II B, launching it early the next year and selling it alongside its upright sibling for a while. It put the cylinders below the propeller line, greatly improving the pilot's view, and the upright soon faded from their sales efforts. All future versions from the Hermes IV on would follow suit, as would Halford's de Havilland Gipsy range.

Cirrus Hermes Engineering Company Limited

In 1934 the company was bought up by Blackburn and moved to their base at Brough in Yorkshire. It remained a separate company under the same name but without the hyphen. Two new variants, apparently rationalising the range, were probably already under development and the Cirrus-Hermes Engineering Company Limited presently introduced the Cirrus Minor and Cirrus Major, in the same power ranges respectively as the Cirrus and Hermes types.

Blackburn Aircraft Cirrus Engines Division

With the new range in place, Blackburn swallowed the company into its own organization as its Cirrus Engine Division. The scaled-down Cirrus Midget was a development which was mentioned a few times in Flight but did not enter production. By the end of WWII Blackburn's range covered the Cirrus Minor II and Major II and III. Then in 1948 it introduced the ultimate fuel-injected version, the Cirrus Bombardier. By the late 1950s Cirrus manufacture seems to vanish from sight, eclipsed by the structurally more efficient and hence lighter flat-four arrangement.

Information is hard to find, especially on the post-Halford years. Much of this history comes from four sources; early history from Taylor's biography of Halford, Boxkite to Jet, and Sharp's history of de Havilland titled simply DH, with the fuller picture from Gunston's World Encyclopedia of Aero Engines and the many advertisements for Cirrus engines in the trade press, archived by Aviation Ancestry and findable at http://aviationancestry.co.uk/?searchQuery=cirrus&startYear=1925&endYear=1957

But that is just about it. Who took over the development after Halford left? I have heard that Philips and Powys of Miles aircraft fame were involved, but is there any truth in that? Who owned and ran all these various interim companies? What were the technical changes introduced with the post-Halford variants? Were 1929 contemporaries the American Cirrus III and Cirrus Hermes technically related? Did any others besides the Midget fall by the wayside? What obscure planes did they end up in - or not - after all? All snippets gratefully received!

Aircraft Disposal Company (ADC)

Geoffrey de Havilland was mulling over what would become the Moth and realised that there was no suitable engine available: it had to be around 60-80 hp, but lighter and more reliable than the old workhorses. Meanwhile Major Frank Halford had revamped the old Renault V8 engine for the Aircraft Disposal Company, who had acquired hundreds if not thousands of them as WWI surplus. Its power doubled, it was being sold as the Airdisco. De Havilland had the bright idea of taking half the Renault and performing a similar miracle on it to create a four-cylinder inline. Halford took some persuading, and the result was the ADC Cirrus. The DH.60 Cirrus Moth launched it into the skies and into history. Developed variants the Cirrus II and III soon followed.

American Cirrus Engines Inc.

With the appearance of the III in 1929, American Cirrus Engines Inc. was set up to license-manufacture its own improved Cirrus III for the US market.

Cirrus Aero Engines Ltd

Presently de Havilland asked Halford to develop a more modern equivalent from scratch, which would become the Gipsy series. The engine designer had already severed his relationship with ADC, who were beginning to run out of the old Renaults and so Cirrus Aero Engines Ltd was formed, operating from the same address as ADC but without Halford, to start manufacturing the Cirrus range from scratch. They launched the improved Cirrus Hermes in 1929.

Cirrus-Hermes Engineering Company Limited

In 1931 the Cirrus-Hermes Engineering Company Limited was set up at Croydon, where they further developed the Cirrus-Hermes II and III. They next turned the Hermes II upside down as the II B, launching it early the next year and selling it alongside its upright sibling for a while. It put the cylinders below the propeller line, greatly improving the pilot's view, and the upright soon faded from their sales efforts. All future versions from the Hermes IV on would follow suit, as would Halford's de Havilland Gipsy range.

Cirrus Hermes Engineering Company Limited

In 1934 the company was bought up by Blackburn and moved to their base at Brough in Yorkshire. It remained a separate company under the same name but without the hyphen. Two new variants, apparently rationalising the range, were probably already under development and the Cirrus-Hermes Engineering Company Limited presently introduced the Cirrus Minor and Cirrus Major, in the same power ranges respectively as the Cirrus and Hermes types.

Blackburn Aircraft Cirrus Engines Division

With the new range in place, Blackburn swallowed the company into its own organization as its Cirrus Engine Division. The scaled-down Cirrus Midget was a development which was mentioned a few times in Flight but did not enter production. By the end of WWII Blackburn's range covered the Cirrus Minor II and Major II and III. Then in 1948 it introduced the ultimate fuel-injected version, the Cirrus Bombardier. By the late 1950s Cirrus manufacture seems to vanish from sight, eclipsed by the structurally more efficient and hence lighter flat-four arrangement.

Information is hard to find, especially on the post-Halford years. Much of this history comes from four sources; early history from Taylor's biography of Halford, Boxkite to Jet, and Sharp's history of de Havilland titled simply DH, with the fuller picture from Gunston's World Encyclopedia of Aero Engines and the many advertisements for Cirrus engines in the trade press, archived by Aviation Ancestry and findable at http://aviationancestry.co.uk/?searchQuery=cirrus&startYear=1925&endYear=1957

But that is just about it. Who took over the development after Halford left? I have heard that Philips and Powys of Miles aircraft fame were involved, but is there any truth in that? Who owned and ran all these various interim companies? What were the technical changes introduced with the post-Halford variants? Were 1929 contemporaries the American Cirrus III and Cirrus Hermes technically related? Did any others besides the Midget fall by the wayside? What obscure planes did they end up in - or not - after all? All snippets gratefully received!

Last edited: