- Joined

- 9 October 2009

- Messages

- 21,973

- Reaction score

- 13,622

Air Cushion Vehicle Operator Training System (ACVOTS)

http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a221417.pdf

http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a221412.pdf

http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a221413.pdf

http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a221416.pdf

http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a221417.pdf

http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a221412.pdf

http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a221413.pdf

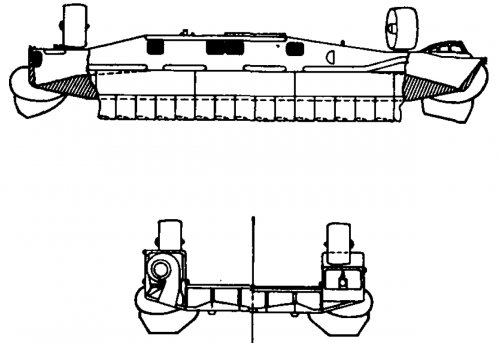

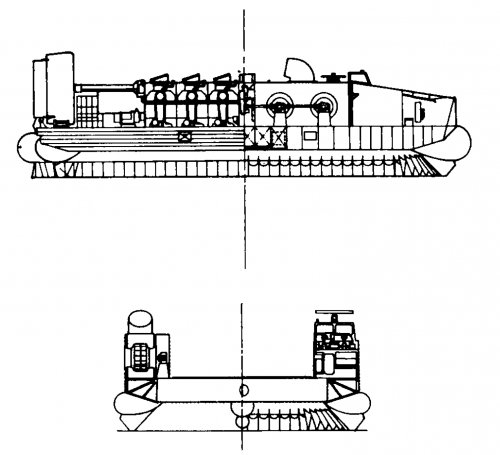

This Air Cushion Vehicle Operator Training System (ACVOTS) Simulator Requirements Analysis was conducted at the direction of the David Taylor Naval Ship Research and Development Center to define the role of simulation in Air Cushion Vehicle (ACV) operator training and to make recommendations concerning potential training devices for the ACVOTS program. Two advanced development ACVs, designated JEFF(A) and JEFF(B), are currently being tested under the Navy's Amphibious Assault Landing Craft (AALC) program. Focus in this analysis was on the JEFF(B) at the AALC Experimental Trials Unit (ETU) due to its projected similarities with the Landing Craft, Air Cushion (LCAC), the first Navy fleet ACV. Recommendations for ACVOTS long-term LCAC operator training program training device procurement were developed as a result of a detailed hands-on training requirements analysis. A draft military specification, Procedures for Simulator Requirements Analysis, MIL-T-XXXXX, was used as a guide in performance of this analysis. Although recommendations contained herein should be implemented prior to and during the short and mid-term LCAC training program, they affect only the long-term program, beginning with LCAC follow-on training.

http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a221416.pdf