Avimimus

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 15 December 2007

- Messages

- 2,235

- Reaction score

- 501

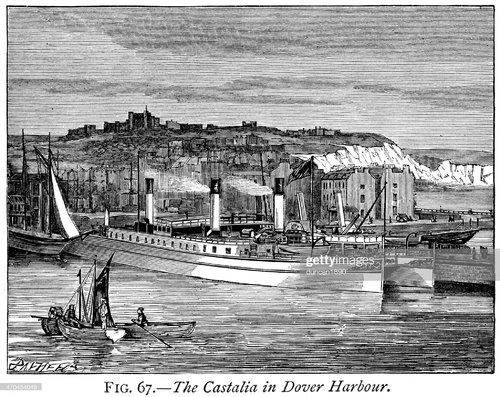

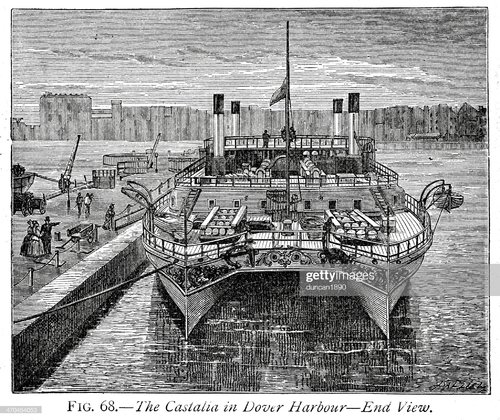

Paddle-wheels were of limited utility for warships due to vulnerability to enemy fire and taking space from the broadside...

So, in the brief period before screw propulsion becoming dominant why not use a bimarana and simply put the paddles in the centre?

So, in the brief period before screw propulsion becoming dominant why not use a bimarana and simply put the paddles in the centre?