As

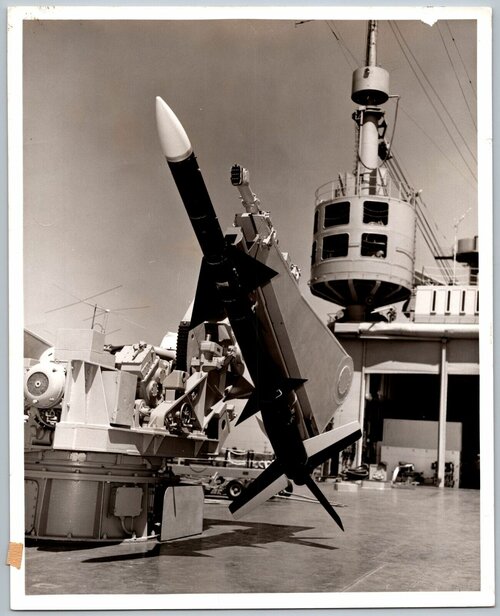

@TomS points out, I don't think we are talking just sticking any given AIM-7E on top of a Polaris here but a Sparrow derivative in a relatively elastic sense.

It is difficult to track this project as it was canned, ostensibly to protect Polaris stocks in the early-60s but was looked into again late-60s/early-70s depending on where you read. The details though are vague to say the least! The concept was at one point based on Polaris/Sparrow but not necessarily so throughout the Early Spring programme.

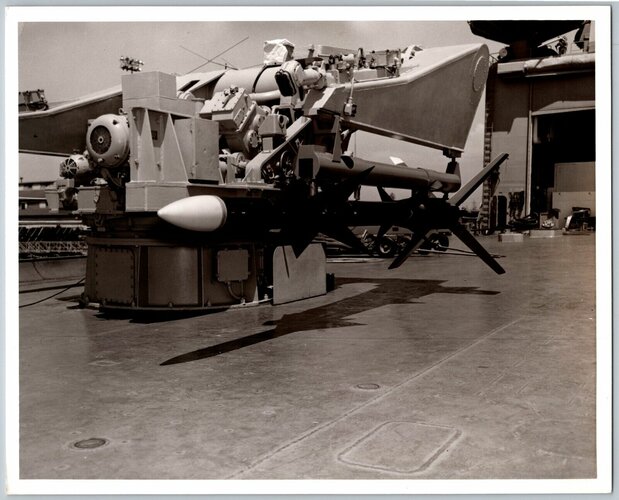

As I understand it, having read multiple, slightly differing descriptions, the plan was to have the Polaris launch the Sparrow-stage into the target's path, which would proceed to "hover" for up to 90 seconds (motor burn out time?) and prosecute the target with a fairly conventional proximity warhead. The appeal of the project was that the entire launch complex, whether ship or sub (the latter needing off-board targetting obviously) could travel to the target's orbit, something Vandenburg couldn't do!

Why didn't it happen? Well first off, we are working with decades-old layperson descriptions which are necessarily simplistic. So I think claiming LTV and Raytheon understood too little is unfounded at best. From what I can gather, the chief concern was the afore-mentioned Polaris stocks but I also read that the ability to conduct on-orbit inspection was a concern. This ultimately led the USAF toward Blue Gemini as I understand it.

In the link above, it is mentioned that Raytheon were refused permission to pursue a camera in the Sparrow nose but I think that this is somewhat lacking in detail. It is likely that relaying a TV signal back to the surface for a remote visual inspection and giving the Sparrow a man-in-the-loop capability was either not technically feasible (less than 90 seconds is tight timing to be certain), prohibitively expensive or both. Between that and the USAF lobbying for dominion is I think why it was ultimately not proceeded with.

Earlier, the USN looked at various other ASAT projects such as NOTS, Caleb, Hi-Ho(e) and a project called Skipper which apparently investigated a Scout-launched "buckshot" or pellet warhead (the trouble with searching for navy and skipper is obvious!). The USN was obviously quite invested in ASAT in the 1960s. If a would-be author could reach better sources, it would certainly be worthy of a book!