- Joined

- 21 January 2015

- Messages

- 12,164

- Reaction score

- 16,385

Spybirds: POPPY 8 and the dawn of satellite ocean surveillance

by Dwayne A. Day

Monday, May 10, 2021

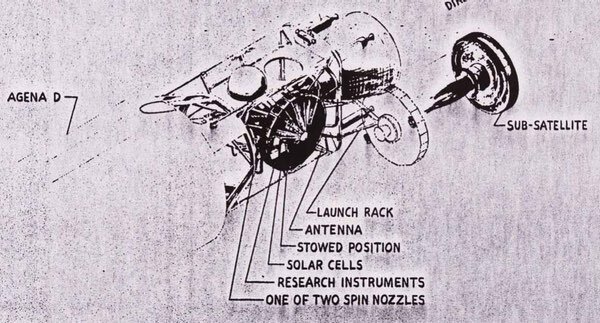

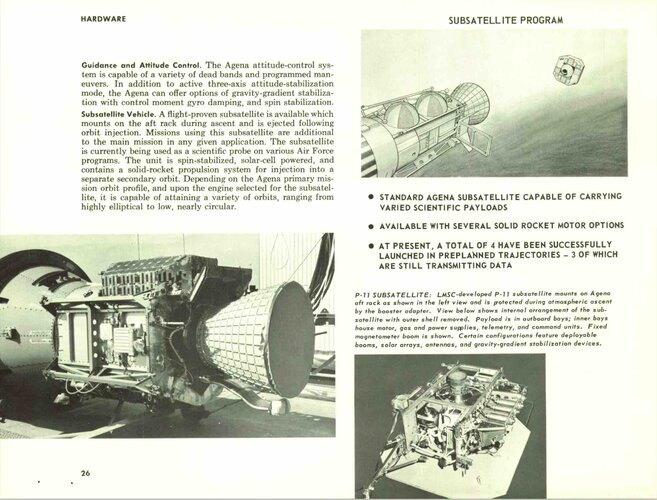

At the end of September 1969, a Thor-Agena rocket roared off its launch pad in California and climbed high over the Pacific Ocean, heading south. The rocket dropped its stubby pencil-like solid booster motors not very long after lifting off and continued its arc. A few minutes later, its first stage, burning a mixture of kerosene and liquid oxygen, ran low on fuel and its engine shut down. The Agena upper stage separated and small motors fired, pushing it away and forcing the fuel in its tanks to settle to the rear, and in moments its Bell rocket engine ignited, pushing it faster and higher. Its bulbous nose cone separated and flew away, revealing a cluster of four shiny, egg-shaped satellites surrounding a small pointy object. Upon reaching orbital velocity the Agena’s engine shut down and the shiny satellites began to pop off, pushed away by springs. Each satellite was about the size of a toddler, and collectively they were known as POPPY 8. They were followed by several other satellites that also separated from the front of the Agena. Moments later, various small satellites were pushed off the rear of the Agena. Then came the finale: at the rear of the Agena, a box-shaped satellite the size of a fat suitcase and named WESTON rotated back on a hinge and was shoved away on springs before firing its solid rocket motor and heading to a higher orbit.

In all, ten satellites were pushed off the Agena that day. There were no rocketcams to record the deployment, and there was no reporting of the event to the press. Of the ten satellites, six were top secret, their missions unknown except to an exclusive cadre of intelligence experts possessing the proper security clearances. Today, due to declassifications by the National Reconnaissance Office, it has become apparent that this launch represented a significant turning point in the history of satellite signals intelligence, when satellites were no longer collecting data to be analyzed at a future time, but to be used in near-real-time, to support military forces. Because as soon as POPPY 8’s satellites reached orbit, they began hunting for Soviet warships on the high seas.

by Dwayne A. Day

Monday, May 10, 2021

At the end of September 1969, a Thor-Agena rocket roared off its launch pad in California and climbed high over the Pacific Ocean, heading south. The rocket dropped its stubby pencil-like solid booster motors not very long after lifting off and continued its arc. A few minutes later, its first stage, burning a mixture of kerosene and liquid oxygen, ran low on fuel and its engine shut down. The Agena upper stage separated and small motors fired, pushing it away and forcing the fuel in its tanks to settle to the rear, and in moments its Bell rocket engine ignited, pushing it faster and higher. Its bulbous nose cone separated and flew away, revealing a cluster of four shiny, egg-shaped satellites surrounding a small pointy object. Upon reaching orbital velocity the Agena’s engine shut down and the shiny satellites began to pop off, pushed away by springs. Each satellite was about the size of a toddler, and collectively they were known as POPPY 8. They were followed by several other satellites that also separated from the front of the Agena. Moments later, various small satellites were pushed off the rear of the Agena. Then came the finale: at the rear of the Agena, a box-shaped satellite the size of a fat suitcase and named WESTON rotated back on a hinge and was shoved away on springs before firing its solid rocket motor and heading to a higher orbit.

In all, ten satellites were pushed off the Agena that day. There were no rocketcams to record the deployment, and there was no reporting of the event to the press. Of the ten satellites, six were top secret, their missions unknown except to an exclusive cadre of intelligence experts possessing the proper security clearances. Today, due to declassifications by the National Reconnaissance Office, it has become apparent that this launch represented a significant turning point in the history of satellite signals intelligence, when satellites were no longer collecting data to be analyzed at a future time, but to be used in near-real-time, to support military forces. Because as soon as POPPY 8’s satellites reached orbit, they began hunting for Soviet warships on the high seas.