Sikorsky Evolves Raider Into FARA Armed Scout Contender

Jul 4, 2019

Graham Warwick | Aviation Week & Space Technology

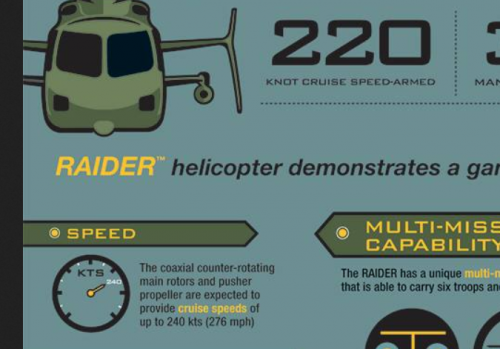

On a hazy Florida morning, a sleek black helicopter makes a high-speed pass, close to 200 kt., the sound of its tail-mounted propeller unique for a rotorcraft. Seconds later, the noise changes as the prop bites into the humid air and the helicopter reverses down the runway and into a tail-high pirouette, circling with its nose laser-focused on a spot on the ground.

This is Sikorsky’s S-97 Raider, being put through its paces before a select group of suppliers the company wants on board to support its bid to build the U.S. Army’s next armed scout—the Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft (FARA).

Sikorsky is one of five companies chasing two contracts to build prototypes for a competitive flyoff in 2023. If successful, FARA would be the fourth instantiation of Sikorsky’s X2 high-speed helicopter configuration comprising the original 6,000-lb. technology demonstrator, the 11,500-lb. S-97 Raider and the 33,000-lb. Sikorsky-Boeing SB-1 Defiant demonstrator also now in testing.

- FARA to be slightly bigger, slower than S-97

- Raider addressing drag, vibration challenges

This line of aircraft has its origins in 2005 when, seeking to differentiate itself from other helicopter manufacturers and after analyzing a range of configurations, Sikorsky returned to the design of its XH-59 Advancing Blade Concept (ABC) coaxial compound helicopter demonstrator. First flown in 1973, this achieved 238 kt. in level flight.

To overcome the ABC’s drawbacks of complexity, vibration and high fuel consumption, Sikorsky applied technologies developed over the intervening years, including carbon-fiber blades and airframe, fly-by-wire flight controls, integrated propulsion system and active vibration control. The result was the X2 demonstrator, which in 2010 achieved 250 kt. in level flight with power still in hand.

The next step was to use the configuration “to make something useful,” says Steve Weiner, director of engineering sciences and “father of the X2.” The result was the S-97 light tactical helicopter, designed around the Army’s Armed Aerial Scout (AAS) requirements. Sikorsky and its supplier partners launched an industry-funded program to build two prototypes, the first of which flew in May 2015.

AAS was canceled in 2013, with the Army blaming budget sequestration. It then retired the Bell OH-58D Kiowa Warrior armed scout that AAS was to replace, and its role was transferred to the Boeing AH-64E Apache. But the Army acknowledges the attack helicopter is not best suited to armed reconnaissance, and in 2018 FARA emerged as an urgent requirement to field 200 new armed scouts beginning in 2028.

On paper, Sikorsky looks well placed to win FARA. The company, its parent Lockheed Martin and its industry partners have invested about $300 million in the Raider program, says Chris Van Buiten, vice president of Sikorsky Innovations. The second prototype has exceeded 200 kt. in flight testing, and FARA would be an evolution of the S-97 configuration, not an entirely new design.

But Sikorsky faces a challenge. To enable a competition, the Army has trimmed its requirements for FARA, setting a minimum speed of 180 kt.—fast for a conventional helicopter, but slow for the X2. That speed requirement pits Sikorsky’s coaxial-rotor compound design against single-main-rotor helicopters and brings the affordability of its more capable, but more complex configuration into sharp focus.

Propulsor reverse thrust allows the Raider to point its nose at a target. Credit: Lockheed Martin

Tim Malia, Sikorsky’s director of future vertical lift–light, describes the company’s driving priorities for FARA as a triangle, with schedule, performance and affordability as the three sides. The Army has made clear that “schedule is king,” he says, but to win the company must also get the other two right.

Sikorsky should be in a good position on schedule. The Raider has already logged more than 55 hr. of flight testing, reaching 207 kt. in level flight and pulling 2g in maneuvers. The first prototype was damaged in a hard landing in August 2017, but the second aircraft has been transferred to the FARA team, and flight testing refocused on reducing the risk in Sikorsky’s proposal.

The Raider was showcased to industry partners (see video), and the press, on June 25 with a demonstration at Sikorsky’s development flight center in West Palm Beach. This highlighted unique capabilities enabled by the compound-helicopter’s combination of rigid coaxial rotors and tail-mounted propulsor.

There are two 34-ft.-dia. contrarotating four-blade rotors. The blades are stiff and the hubs hingeless so the rotors can be mounted close together, reducing drag. This configuration enables higher airspeed because the lift is generated by the advancing blades on each side, allowing the pitch of the retreating blades to be reduced and avoiding the blade stall that limits the speed of conventional helicopters.

Rotor speed is scheduled with tip Mach number, and reduces to a minimum of 85% rpm as airspeed increases to prevent the advancing blades from going supersonic. The distance between the tips of the upper and lower rotors is actively sensed. Two-thirds of the tip gap is to allow for blade flexing during maneuvers and one-third is the safety margin, says Bill Fell, senior experimental test pilot.

In the August 2017 accident, a flight-control software error led to a roll rate on liftoff three times greater than intended.

Gyroscopic forces caused the rotor tips to collide. “We fixed the error in the code and we now completely understand the physics,” he says. “Our job is to make sure it never happens again.”

The Raider is powered by a single 2,600-shp General Electric YT706 turboshaft. In hover and at low speed, power goes to the rotors and the propulsor is declutched. As speed increases and the propulsor is engaged, power shifts to the six-blade, variable-pitch pusher propeller. At high speed, 90% of the power goes to the propulsor, says Fell.

Pilots increase or decrease propulsor thrust using a “beep” switch on the central collective lever. This moves propeller pitch through its range of +50 to –20 deg. The rotors can take up to 1,800 shp of power, the propeller 2,200 shp. The engine cannot provide full power to both simultaneously, so the integrated digital engine and flight controls automatically maintain the rotor power required for lift and limit the propulsor to the excess power available.

Coaxial rigid rotors provide increased agility, as well as higher speed. Credit: Lockheed Martin

The Raider can fly at up to 150 kt. with the propeller disengaged. This allows the helicopter to dash at high speed then declutch the propulsor to reduce the noise on approach to the target. There is no anti-torque tail rotor. As the prototype demonstrated during two passes, there is a significant reduction in acoustic detectability when the propeller is disengaged.

The propulsor offers other unique capabilities. Conventional helicopters tilt nose-down to accelerate and nose-up to decelerate. Using forward or reverse thrust on the propeller allows the Raider to slow down or speed up with a level fuselage attitude. This is valuable when carrying casualties or passengers, says Van Buiten. Tactically, using the propeller can prevent the aircraft popping up into the sights of enemy defenses when flying over a ridge during high-speed nap-to-the-earth flight.

By using reverse thrust on the propeller, counteracted by forward thrust on the rotors, the S-97’s fuselage can be pointed downwards. Fell showed how this allows sensors or weapons to dwell on the target as the Raider circled, nose down. Forward thrust on the propeller, balanced by rearward thrust on the rotors, allows the fuselage to be pointed upward. These are capabilities conventional single-rotor helicopters do not have, but the value of which must still be demonstrated to the customer.

Although speed is no longer the focus of testing, Sikorsky still hopes to achieve the Raider’s 220-kt. design goal. “We underestimated the drag,” says Fell, “but there are dials we can tweak.” Sikorsky is preparing to install a new set of rotor blades, redesigned to reduce drag and vibration at high speed—another area of concern with the rigid-rotor helicopter.

In addition to being stiff, the Raider’s blades are complex, with changing thickness and chord across five different airfoil sections from root to tip.

Fell says vibration in the Raider at more than 200 kt. is similar to that in the UH-60 Black Hawk at 150 kt. But the potential impact of vibration on crew fatigue, aircraft systems and component lives is a concern, although the S-97 is equipped with an active vibration control (AVC) system. The new blades have been redesigned to improve aerodynamic efficiency, but how they attach to the hingeless hubs also has been modified, says Fell, to reduce the transmission of vibratory forces from the blades into the airframe.

The importance of minimizing vibration was illustrated during the demonstration flight. Fell says the flight plan called for a 200-kt. high-speed pass, but maximum speed was held to 190 kt. “We planned 200 kt., but a new script file in the AVC did not work out and there was no reason to push it,” he says. AVC actively cancels vibration by introducing opposing forces into the airframe.

Mitigating vibration is one example of risk-reduction testing the Raider will perform for the FARA team, which is nearing its preliminary design review. Because the Army has reduced its speed requirement, Sikorsky’s FARA design will be “detuned” relative to the Raider, but will still have more growth potential than a single-rotor helicopter already at the limits of its capability at 180 kt, says Malia.

With a larger, 39-ft.-dia. rotor system, a higher, 14,000-lb. gross weight and a single, 3,000-shp General Electric T901 Improved Turbine Engine, the FARA will be slower than the Raider, he says. There will be other changes. The fuselage will be stretched to accommodate two 80-in. long internal bays for weapons, air-launched unmanned aircraft and other mission payloads. There will be no external stores on FARA, Malia says, and these bays will essentially replace the Raider’s passenger cabin.

The fuselage will be tuned to minimize vibration, he says. Sikorsky has already selected Swift Engineering to build the airframe for the FARA prototype. Aurora Flight Sciences built the Raider fuselage, but is now owned by Boeing, and Swift manufactured the airframe for the SB-1 Defiant. Suppliers of other long-lead components are also already on board, Malia says, to meet a schedule that calls for contract award in March 2020, flight in first-quarter fiscal 2023 and the Army flyoff in the fourth quarter of that year.

The landing-gear arrangement is different on the FARA design, and there are changes to the propulsor. On the Raider, when the propeller is disengaged a limited-slip clutch keeps it turning at 200 rpm. This is to avoid heat damage to a blade by the engine exhaust, which is located above the tail, just forward of the prop. On FARA, as on the Defiant, the exhaust design is different and the propulsor will stop completely. Sikorsky could also redesign the propeller blades to reduce noise in high-speed flight.

For Sikorsky, tailoring its X2 configuration to the less-demanding FARA requirements is crucial to making it affordable.

But the company wants to preserve the design’s inherent growth capability—particularly in speed—because it sees this as a differentiator. After decades of false starts, the Army urgently needs an armed scout. A conventional helicopter could do the job, but Sikorsky needs the service to take the long-term view and pick a configuration still at the beginning of its evolution.