hagaricus

ACCESS: Barclaycard

- Joined

- 5 November 2010

- Messages

- 177

- Reaction score

- 172

Can we allow complete fantasy here? If so this is a scenario I keep coming back to:

You have fallen through a timewarp.

It is April 12th 1912 and you are on a ship in mid-atlantic.

Which way it is going is up to you.

You get caught as a stowaway and put to work doing menial labour on board.

You realise the Titanic is about to sink, and manage to engage many of your shipmates in quite large bets on it sinking.

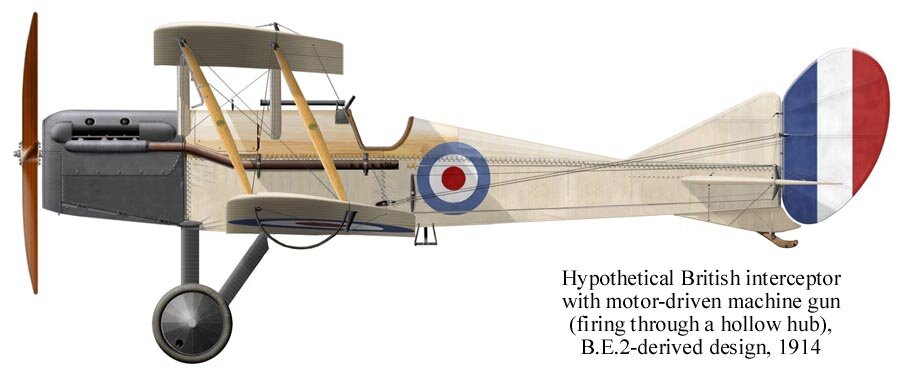

You walk off the ship in the country of your choice a moderately rich person, and by way of your knowledge of the future, manage to increase this wealth to the point that in september 1912 you can start developing an aircraft.

What do you build?

You have fallen through a timewarp.

It is April 12th 1912 and you are on a ship in mid-atlantic.

Which way it is going is up to you.

You get caught as a stowaway and put to work doing menial labour on board.

You realise the Titanic is about to sink, and manage to engage many of your shipmates in quite large bets on it sinking.

You walk off the ship in the country of your choice a moderately rich person, and by way of your knowledge of the future, manage to increase this wealth to the point that in september 1912 you can start developing an aircraft.

What do you build?