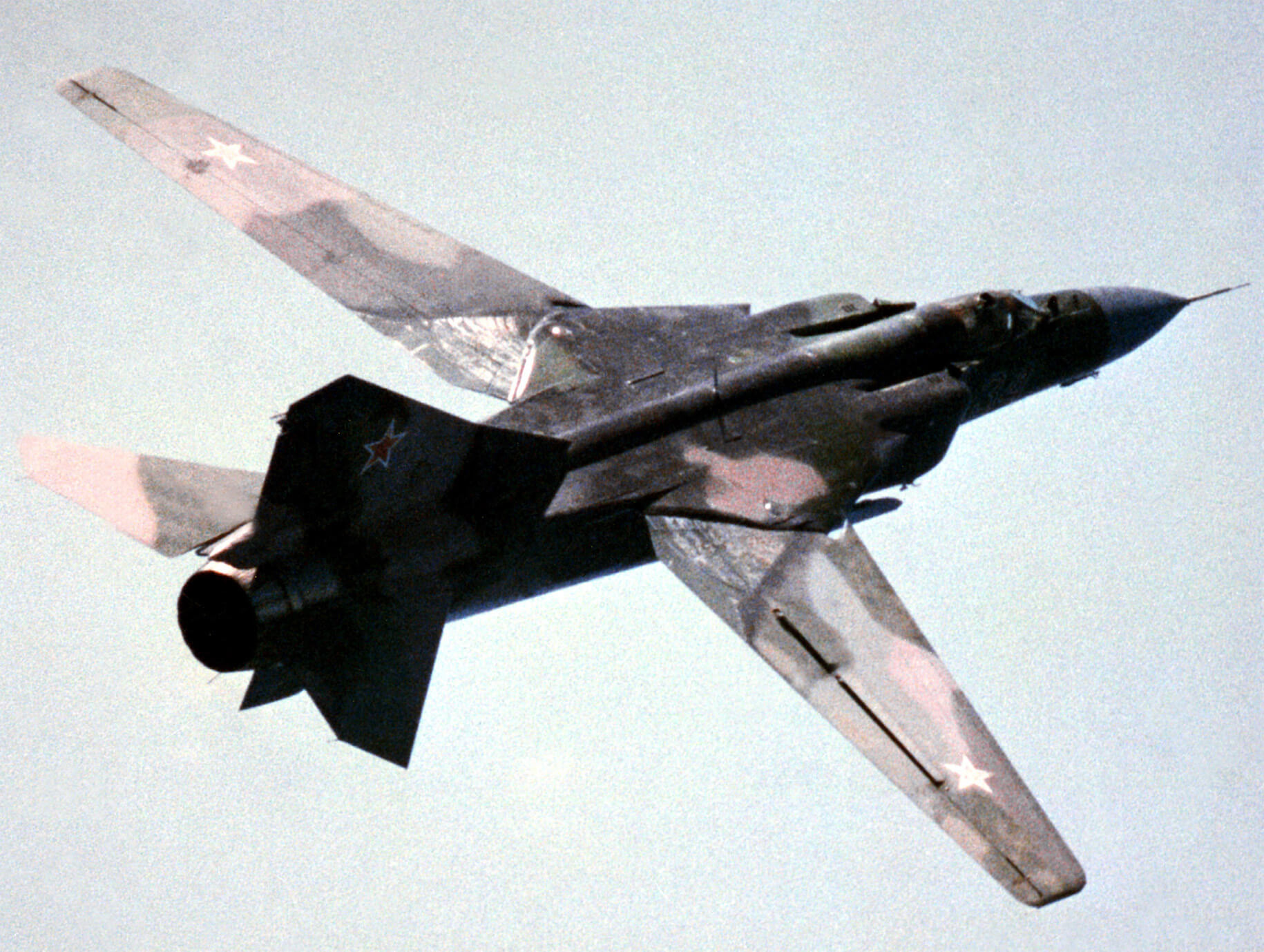

MiG-23MLD - some BVR Considerations and Recomendations

MiG-23MLD’s pros and cons – the Soviet view of the 1980s

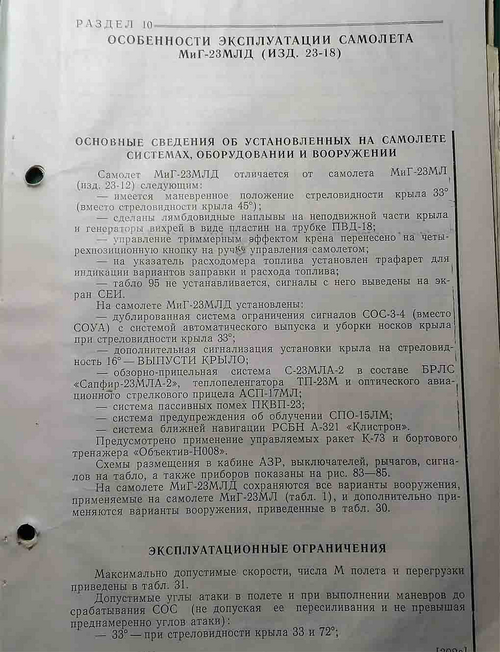

It would be interesting for the Western public to examine and analyse in details the content of a Soviet Air Force supplementary air combat manual. This particular 32-page manual was published not long after the Bekaa Valley clashes.

The manual concludes that the MiG-23MLD(Export) equipped with the Sapfir-23MLAE-2 radar, SPO-15LE RWR, chaff/flare dispensers and last but not least the R-24/R-60MK AAM combination could be considered reasonably capable of holding its own against all types of enemy fighters. However, the edge over the F-15A – the most capable archrival - could be gained only through multiple simultaneous ‘slash-and-dash’ attacks from several directions and from long ranges. These attacks are required to be organised and executed in decisive manner; with a high degree of coordination between the groups when the engagement goes to the WVR phase, and with timely exit from combat.

The docuemnt contains a host of recommendations to the MiG-23MLD pilot and it has apparently been compiled on the basis of the Bekaa Valley clashes analysis of and numerous mock-up combats flown in the VVS-FA training centers in Lipetsk and Mary. Some if not most, of these recommendations may sound more as general rules rather than as specialised air combat instructions for the MiG-23 drivers. However, it would be appropriately to remind that most of those ‘general-and-vital’ rules were obviously disregarded by the Syrian pilots during the June 1982 war, turning out them to suffer the fate of turkey shoots over the Bekaa Valley.

Probably the most important rule, contained into the recommendation chapter of the manual dealing with the BVR combat, is that on the importance of the first attack as it sounds as follows: “In order to achieve surprise in shooting, the MiG-23MLD pilots should spend all of their experience and aggressiveness of into the first attack.” Undoubtedly, this is considered as critical factor since surprise has been proved to be nine-tents of air combat success, both offensive and defensive. Other critical elements in the success of a fighter sweep or CAP operation are the command, control and communications (C3) of the own fighter force. The ability of fighter pilots to find, identify and engage high-value hostile targets in BVR environment avoiding potential threats from a position of advantage, rest in great measure on relative C3 capabilities. According to the then Soviet air superiority doctrine the air superiority operations require well-honed functioning GCI assistance substituting the lack of AWACS assets; therefore the GCI officers had to maintain maximum possible situation awareness, i.e. where air superiority has to be achieved, where and when enemy aircraft would come and from which direction, etc. The Soviets mastered to perfection this highly-redundant – but far from perfect and rather inflexible - concept that turned out to be useful for the Central European theatre with dense ground radar coverage and numerous GCI centers, with some 200-250 radars of various types were believed to be used in a full scale war situation in Central Europe. However, it was not the same sitation being provided for the Third World MiG-23 operators, as the the somewhat inflexible and custom-tailored Soviet GCI concept, hardly provided the most effective command-and-control solution for them (they simply lacked the required infrastructure and training).

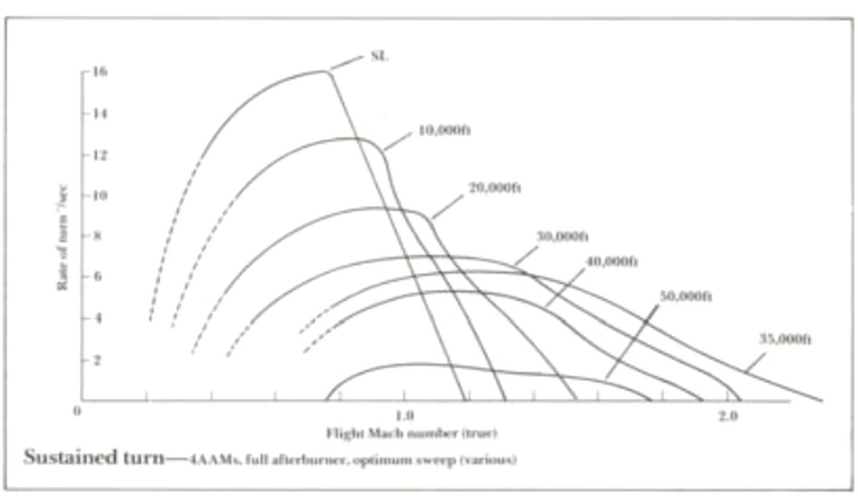

The MiG-23MLD’s radar is said to be capable of detecting fighter-size targets from long distances but it makes the own fighter easily detectable due to the strong emissions which can trigger every and each enemy RWR at a distance of excess of 65nm (120km). In addition, the radar is known as susceptible to active jamming, thus, when flying over own territory with sufficient ground radar coverage, the radar should be switched off and activated only on GCI order. In such cases, the IRST should be the preferred sensor. In order to expand the search zone in a high-threat environment, the Flogger pilot is required to fly a zig-zag pattern with his main attention centered onto the visual search bellow the bottom boundary of the own ground radar coverage (usually bellow 1,000ft [300m] in Central Europe in the 1980s). The purpose of weaving is primarily to allow the pilot to cover his rear quarter more easily (in could be useful to note that most of the MiG-23 kills during the Bekaa Valley were caused by undetected rear-quarter attacks by IDF/AF F-16s using the AIM-9L or F-15As with the Python 3). It is well known that the MiG-23 pilot has ample problems with the rearward and downward field of view as the fighter is designed with a low-drag canopy, faired into the fuselage though the canopy-mounted rear-view mirrors expand to some degree the rearward field of view. Therefore, the MiG-23 pilots would be expected to encounter huge difficulties in keeping a view on a turning bogey or during visual search bellow his aircraft (this is possible only through banking, but the workload on the pilot is excessively high). On the other hand, it has to be noted that the MiG-23MLD is a quick in acceleration thanks to the low-drag airframe and the aerodynamic qualities of the fully-swept wings, and its high speed could increase difficulty encountered by an unseen attacker in satisfying his aiming requirements in the reduced intercept time; this can be used as another defensive factor when flying in enemy or disputed airspace.

During the BVR air combat, the manual recommends strongly that attacks should not be initiated without offensive advantage and the prospect of getting off the first shoot. The general rule: ‘Who shoots first – kills first, in the worst case dictates the engagement’ should be regarded as of particular importance for the MiG-23 community. If the MiG-23 was dictating the engagement, the aircraft could employ to the full extent its advantages as a high-speed ‘chaos’ fighter using ‘slash-and-dash’ attack - a preferable and often the only available method for the MiG-23 community when engaged vs F-16s and F-15s. It is of note that the high-speed energy fighters like the MiG-23 have the option of engaging or disengaging at will, even in the 1980s and 1990s all-aspect BVR and WVR missile environment.

Another possibility is, in favourable tactical situations, groups of well-flown and well-GCI-directed Floggers to ‘gang-up’ of the better turning bogey such as the F-15 or F-16 using multiple aircraft tactics, with ‘snap-up’ attacks. For a reliable radar-ID (also known as Electronic ID or EID) of the detected bandits, several interrogations should be made – as more ID attempts, as little the risk of fratricide. If unknown type of bandit aircraft are encountered, it should be assumed that these may be F-15s – the most capable and hence the most dangerous enemy fighter. The manual stresses that it is prohibited for the MiG-23MLD to close head-on toward any bandit aircraft of unknown type because it is likelihood these to be F-15s possessing better radar performance and longer-range BVR missiles.

It would be also useful to note that an important recommendation to the GCI officers contained in the manual is that during fighter sweep operations it is strictly prohibited for them to vector the MiG-23s in head-on attacks against non-identified bandits because, as noted above, these are likely to be the dangerous F-15s. Nevertheless, if such a situation is unavoidable, then the anti-F-15 tactics, recommended to the MiG-23 pilots and GCI officers is as follows: if the distance to the bandits exceeds 12nm (20km) the MiGs should immediately perform a sharp turn out of the target and got away descending and pulling high-g; the direction of defense break turn depends on the aspect of the threat and usually should be in the closest direction to achieve beam aspect and then to maneuver in order to revert into side-on or tail-on missile attack. If the target is detected side on, than the MiG-23MLD pilots should use chaff and sharp turns in order to evade the Sparrow missiles and them to revert into attack.