- Joined

- 21 January 2015

- Messages

- 12,157

- Reaction score

- 16,374

God’s eye view: HEXADOR and the very high resolution satellite

by Dwayne A. Day

Monday, October 7, 2019

On October 23, 1962, the skies over Cuba were cracked open by the roar of Navy RF-8 Crusader reconnaissance aircraft flying at high speed and very low level. A little over a week earlier, a high-flying U-2 reconnaissance plane had photographed unusual activity on the island. The U-2 photographs had been alarming enough to initiate a major crisis. But what they revealed was hard for untrained people to interpret, and so President John F. Kennedy had authorized risky and provocative low-level reconnaissance flights. Now the Crusaders were screaming over the scrub with their side-looking cameras peering at the various structures and vehicles that dotted the terrain, far closer than the high-flying U-2. When they returned to Florida and their film was processed and looked at by trained human eyes—and even untrained human eyes—it was clear to everybody who saw them that a very serious problem existed not far from American shores.

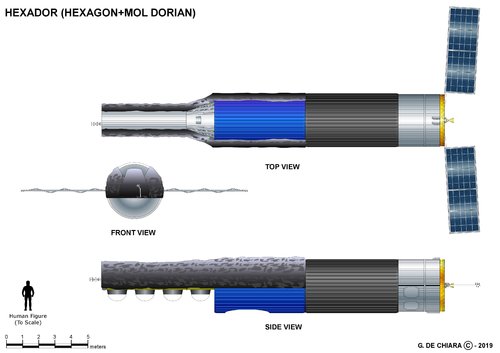

Heavy metal in orbit

By 1968, with both the HEXAGON and the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL)/DORIAN reconnaissance satellites under development, the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) had its hands full working on the next-generation satellite reconnaissance systems. Both spacecraft were big—requiring powerful Titan III launch vehicles to put them in low Earth orbit—and both were also complicated, expensive, and over-budget. So it is surprising that amidst all this work, some within the NRO began discussing developing yet another photographic reconnaissance satellite program, one which remains relatively obscure and little known even today, over five decades later. This program was known as the “Very High Resolution” or VHR reconnaissance satellite, and at least one iteration appears to have been referred to by some as HEXADOR, as a combination of HEXAGON and DORIAN hardware. VHR was supposed to take the kinds of photographs that the RF-8 Crusaders had taken six years earlier, but in areas of the world that no Crusader could fly.