CEPHEIDS AND THEIR RADIAL VELOCITY CURVES

The variable stars that nowadays are collectively called Cepheids are actually an ensemble of different types identifying three main groups: Classical Cepheids, type II Cepheids and anomalous Cepheids. Classical Cepheids are fundamental standard candles of the extragalactic distance scale. They are also important tracers of the young (~50-500 Myr) population in the host galaxy, while anomalous and type II Cepheids are believed to belong to the intermediate-age (few Gyr) and old (>10 Gyr) populations, respectively.

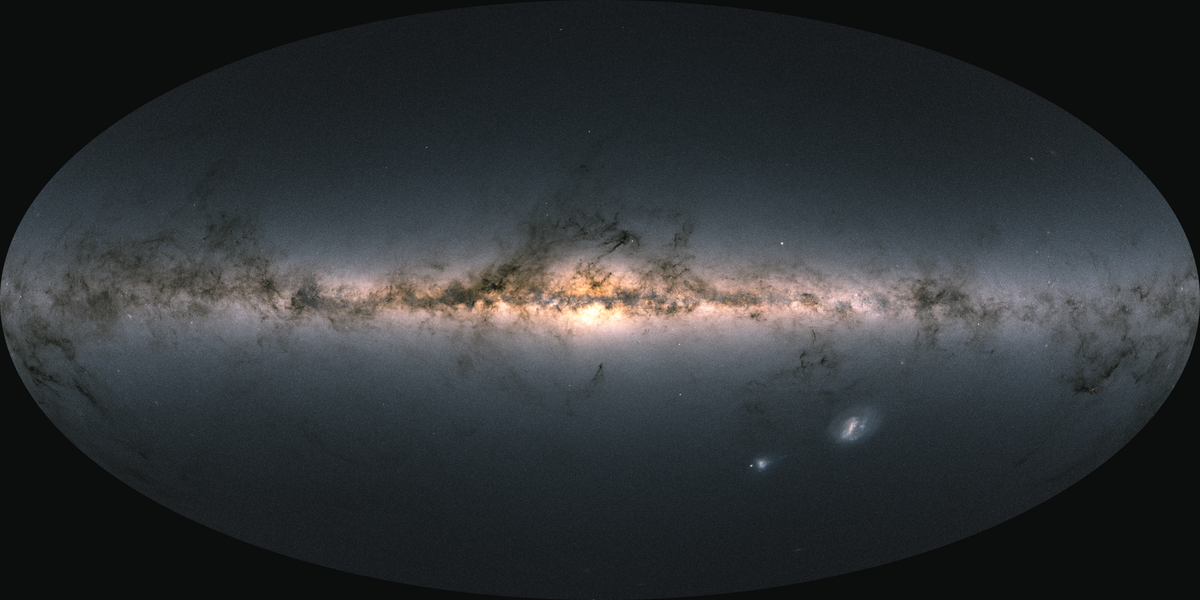

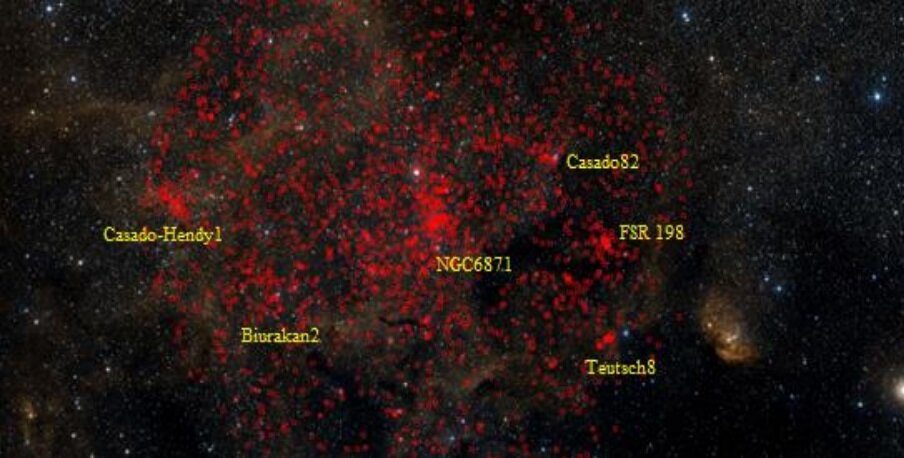

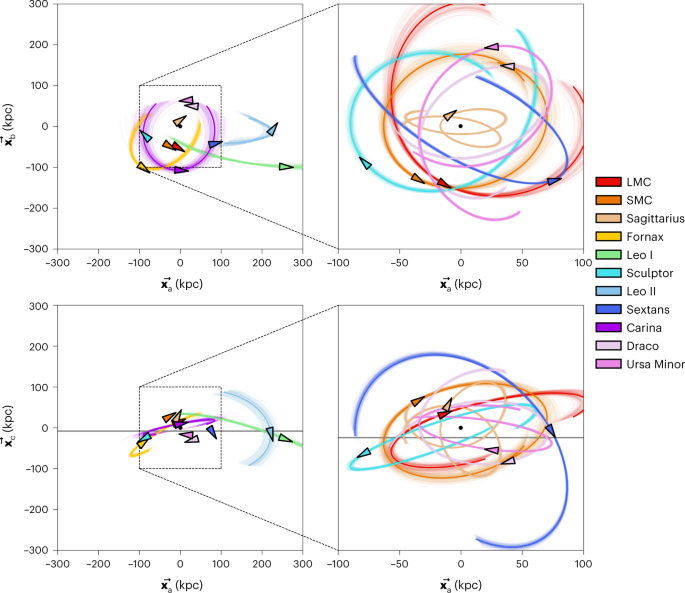

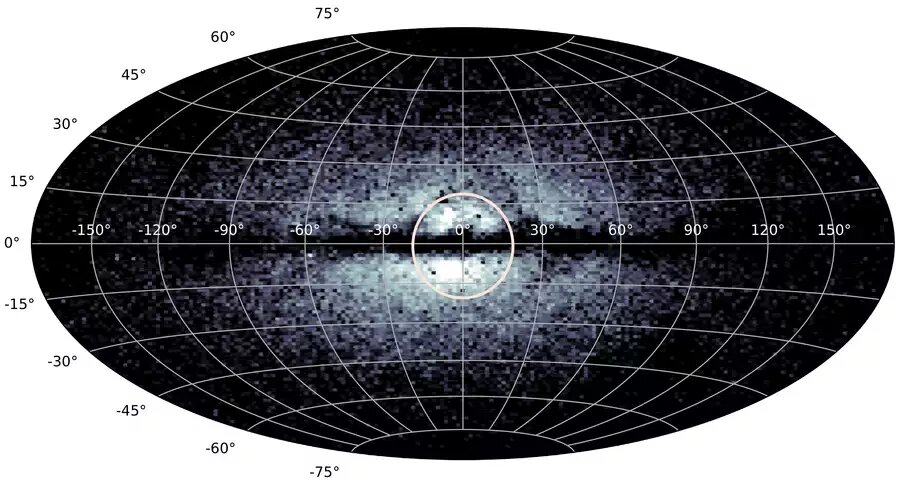

Gaia Data Release 3 (Gaia DR3) will release multi-band light-curves for more than 15,000 Cepheids of all types in five different environments, namely, the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, the Andromeda (M31) and Triangulum (M33) galaxies and the Milky Way (including its cluster population and its small satellite dwarf galaxies).

These pulsating stars have been confirmed and fully characterised by the Specific Object Study pipeline for Cepheids and RR Lyrae stars (called SOS Cep&RRL, Clementini et al. 2016) developed by Coordination Unit 7 (CU7; variability processing) of the Gaia Data Processing and Analysis Consortium. Periods, amplitudes of the GBP, G and GRP light variations, and mean magnitudes computed as an intensity-average over the full pulsation cycle, will be published for these Cepheids, along with the parameters resulting from the Fourier decomposition of their G-band light curves (φ21, φ31, R21 and R31; see e.g. Clementini et al. 2016).

In addition, radial velocity time-series data will be released in Gaia DR3 for a subsample of about 800 Cepheids (see Ripepi et al. 2022, the paper describing the specific processing and validation of all-sky Cepheid variables released in Gaia DR3, for full details).

The light and radial velocity curves for a sample of classical Cepheids in the period range from ~7 to ~13 days are shown in Figure 1. The extraordinary precision of the Gaia data (uncertainties on the individual measurements are comparable with the symbol sizes) allows us to appreciate the “Hertzsprung Progression”, discovered about one century ago by the Danish astronomer E. Hertzsprung. This feature consists in the observation of a “bump” both in the light and radial velocity curves of classical Cepheids in the period range of 6 - 15 days, whose position moves from the descending to the rising branch of the light curve as the period increases. The “bump” is clearly discernible in the descending branch of the Cepheid BM Pup (P~7.2 days, top left in Figure 1); it moves backwards in phase becoming almost equivalent in magnitude to the main maximum for P~8.2 days, reaching the bottom of the ascending branch for V1364 Cyg (P~13 days, bottom right). The physical origin of the bump is not yet completely understood, however it is believed to be due to the resonance between the second overtone and the fundamental modes and it takes place when the period ratio between these two modes is close to 0.5.

The evolution of the bump phase as the period increases is observed and predicted from theoretical pulsation models to depend on the metallicity of the host galaxy. Indeed both models and observations point towards a longer period for the centre of the Hertzsprung Progression (the point where the bump reaches the same magnitude as the maximum light, immediately before it re-appears on the rising branch) as the metallicity of the host population decreases. Recent model predictions also suggest a dependence on the Helium abundance and the mass-luminosity relation. The position in period of the centre of the Hertzsprung Progression, accurately determined from Gaia light and radial velocity curves, can thus provide crucial constraints not only on the chemical composition of the observed classical Cepheids but also on the physics of intermediate mass stars.

References

Clementini et al. 2016: “Gaia Data Release 1. The Cepheid and RR Lyrae star pipeline and its application to the south ecliptic pole region”, A&A, 595, A133

Ripepi et al. 2022: “Gaia DR3: Specific processing and validation of all-sky RR Lyrae and Cepheid stars - The Cepheid sample”, A&A, submitted

Credits: ESA/Gaia/DPAC/CU7/CU6/CU5/INAF, Vincenzo Ripepi, Marcella Marconi, Roberto Molinaro, Silvio Leccia, Ilaria Musella (INAF-OACn Naples), Gisella Clementini, Alessia Garofalo (INAF-OAS Bologna), Laurent Eyer (University of Geneva) and the CU7/DPCG, CU5, and CU6 teams.

[Published: 27/05/2022]

www.cosmos.esa.int