It took the team around an hour to get the box precisely aligned and screw in the final bolt. But by 10 a.m. on Wednesday, Sept. 8, LICIACube was fully integrated, putting into place the last major piece of the spacecraft and culminating months of environmental tests and analyses as each of DART’s components have been mounted.

Contributed by the Italian Space Agency (ASI) and designed, built and operated by the Italian aerospace engineering company Argotec, LICIACube (pronounced LEE-cha-cube) has the important task of watching DART’s final maneuver – a deliberate crash into an asteroid – and its effects.

“Seeing LICIACube installed on DART was exciting because this mission breaks new ground for ASI and the whole Italian space sector,” said Simone Pirrotta, LICIACube Project Manager for ASI. “It will be the first Italian satellite ever to operate in deep space, requiring the training of a large and motivated national team that is now well qualified to tackle similar challenges in the future.”

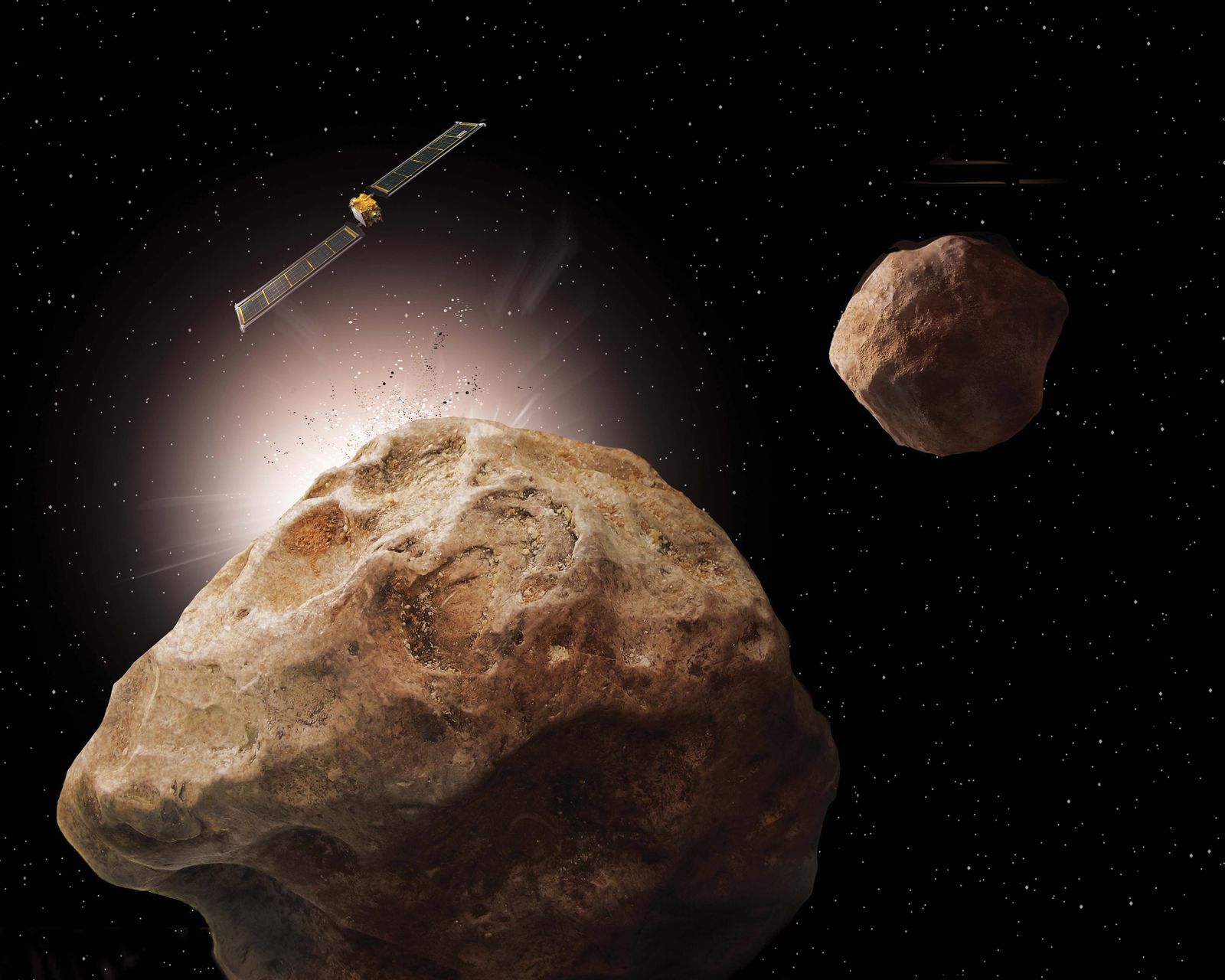

The mission objective of DART, which was designed, built and is managed by APL, is to determine whether flying a spacecraft into a small solar system body at speeds of about 15,000 miles per hour could be a reliable technique to deflect an asteroid if such a hazard were ever discovered to be on a collision course with Earth.

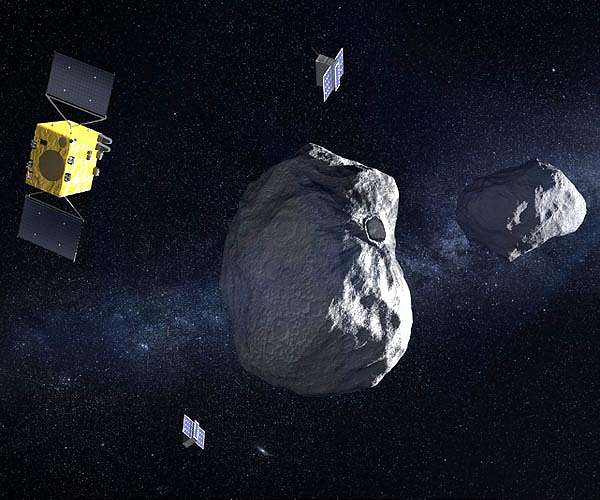

The mission’s target is a binary asteroid system — Didymos and its small moonlet asteroid Dimorphos. Neither poses a threat to Earth, but their orbit around the Sun swings them close enough to the planet that ground-based telescopes can observe the aftermath of DART’s collision and calculate how effective it was at changing Dimorphos’ path. Those observations, along with DART’s main imager DRACO—the Didymos Reconnaissance and Asteroid Camera for Optical navigation—will ultimately achieve all of DART’s mission objectives. But the images LICIACube captures will significantly enhance the mission’s overall knowledge return, and hope to provide spectacular testament of its success.

LICIACube is equipped with two optical cameras, dubbed LUKE (LICIACube Unit Key Explorer) and LEIA (LICIACube Explorer Imaging for Asteroid). These will capture scientific data and inform the microsatellite’s autonomous system by finding and tracking the asteroid throughout the encounter.

The CubeSat will deploy 10 days prior to DART’s kinetic impact, kicking out of its spring-loaded box at roughly 2.5 miles per hour. LICIACube will then use its onboard propulsion system to alter its trajectory, offsetting itself so it flies past Dimorphos around three minutes after the DART impact. That delay will give LICIACube the opportunity to capture images of the impact’s effects, including the resultant plume of ejecta and possibly the newly-formed impact crater, as well as the backside hemispheres of both Didymos and Dimorphos that DART will not see.

“For a first mission, it’s really something,” said Andy Cheng, an APL planetary scientist and lead investigator of DART. “Without LICIACube, there would be no observation of the ejecta cloud,” which can reveal details about how much material was kicked out, how fast it was ejected and in what direction, Cheng said. That information will help further characterize the momentum exchange between DART and the asteroid and, thus, how effective the kinetic impact was at deflecting Dimorphos.

“We are eager to obtain these unique in situ images," said Elisabetta Dotto, LICIACube scientific coordinator from the National Institute for Astrophysics in Rome. “It will be so exciting to study, for the first time, the nature and structure of such weird objects as binary [near-Earth asteroids].”

In the last week of September, DART departed for Vandenberg Space Force Base near Lompoc, California, where it is scheduled to launch in late November on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket. The spacecraft will set course to collide with Dimorphos in fall 2022, which will change the period of the moonlet’s 12-hour orbit around the main body by several minutes. Scientists will use ground-based telescopes to determine the exact change in the orbital period. LICIACube’s X-band communication system will transmit the spacecraft’s imagery back to Earth over the months following DART’s collision.

spacenews.com

spacenews.com