sovanova95

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 13 March 2022

- Messages

- 2

- Reaction score

- 2

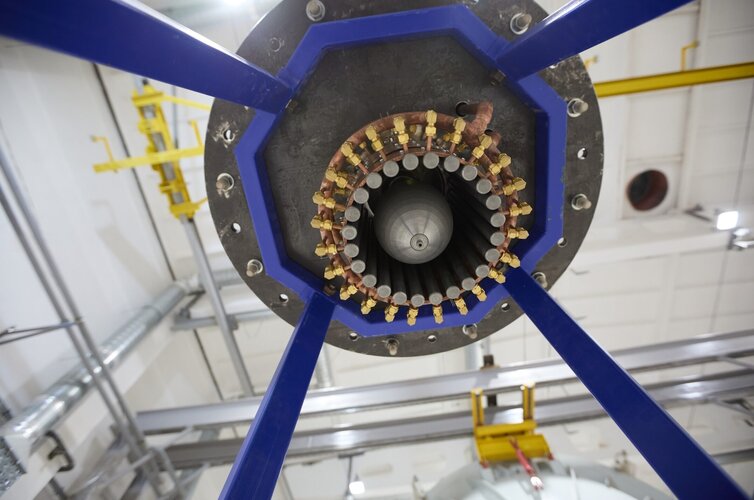

The scientists at Rosatom have developed a laboratory prototype of a plasma electric rocket engine based on a magnetic plasma accelerator, which exhibits improved thrust performance (at least 6 Newtons) and specific impulse (at least 100 kilometers per second). The project is a part of a comprehensive program aimed at advancing nuclear science, engineering, and technology in Russia, which in 2025 emerged as a part of the new national initiative for technological leadership “New Nuclear and Energy Technologies”

A large-scale experimental facility is constructed at the Troitsk site to test the plasma rocket engine prototype and other similar technologies. The diameter of the main equipment of the facility, the vacuum chamber, is 4 meters, and its length is 14 meters. The chamber is planned to be equipped with unique systems for high-efficiency vacuum pumping and heat removal. These systems make it possible to create space-like conditions.

A large-scale experimental facility is constructed at the Troitsk site to test the plasma rocket engine prototype and other similar technologies. The diameter of the main equipment of the facility, the vacuum chamber, is 4 meters, and its length is 14 meters. The chamber is planned to be equipped with unique systems for high-efficiency vacuum pumping and heat removal. These systems make it possible to create space-like conditions.

A large-scale experimental facility is constructed at the Troitsk site to test the plasma rocket engine prototype and other similar technologies. The diameter of the main equipment of the facility, the vacuum chamber, is 4 meters, and its length is 14 meters. The chamber is planned to be equipped with unique systems for high-efficiency vacuum pumping and heat removal. These systems make it possible to create space-like conditions.

A large-scale experimental facility is constructed at the Troitsk site to test the plasma rocket engine prototype and other similar technologies. The diameter of the main equipment of the facility, the vacuum chamber, is 4 meters, and its length is 14 meters. The chamber is planned to be equipped with unique systems for high-efficiency vacuum pumping and heat removal. These systems make it possible to create space-like conditions.