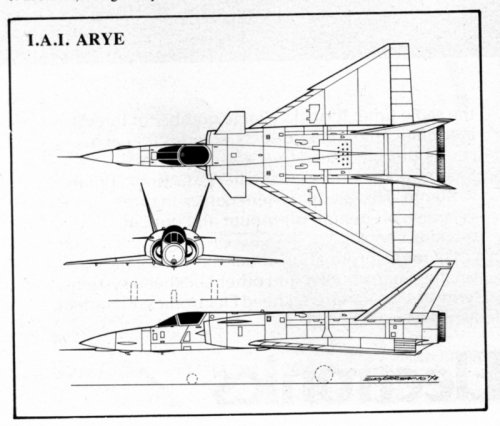

I stumbled upon the Arie project online earlier. What info I found on it says it was essentally a drastically modified Kfir. The one pic I saw shows something that looks like more to it. Any 3 views anywhere? The same article mentions a proposed Super Kfir to be powered by a P & W F-100. Any further info on that one?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

From Super Kfir via Arie and Hadish to the Lavi - 70s IAI fighter studies

- Thread starter frank

- Start date

Matej

Multiuniversal creator

Thanks! I had followed that thread a few weeks ago, but haven't checked it lately. I thought it was done!

Archibald said:look here

http://www.whatifmodelers.com/forum//index.php?showtopic=10733&st=30

You can also browse Key publishing they certainly have a thread on the subject (even uninteresting!)

Thanks! That's pretty much what I had imagined it to look like. I understand its performance was quite improved with that engine. Any info on that?

Matej said:Damn! I found pictures of everything what you want, but I am still unable to find Tier 3 stuff! AAAAAGH!!!

- Joined

- 3 January 2006

- Messages

- 1,223

- Reaction score

- 944

Matej said:Damn! I found pictures of everything what you want, but I am still unable to find Tier 3 stuff! AAAAAGH!!!

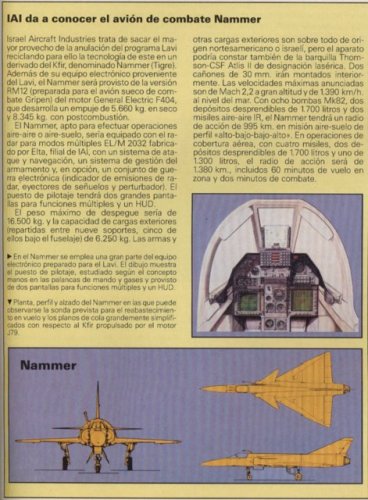

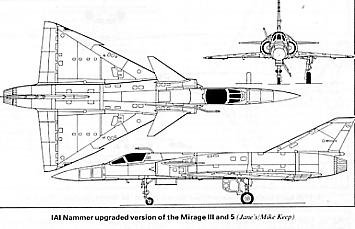

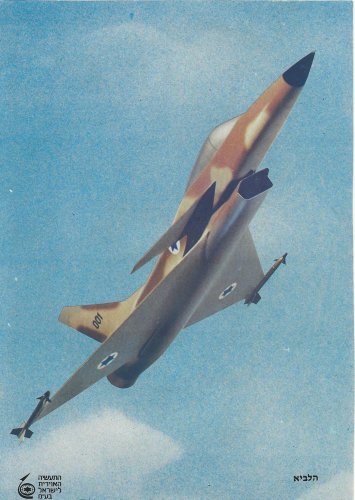

I am familar with this drawing of the Nammer proposal for the early 90s.

Does the drawing depict the F404 or the PW1120 engined version?

Matej

Multiuniversal creator

TinWing said:I am familar with this drawing of the Nammer proposal for the early 90s.

Does the drawing depict the F404 or the PW1120 engined version?

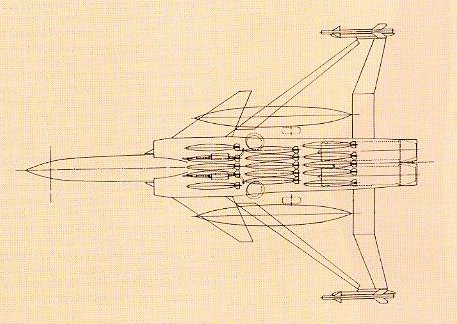

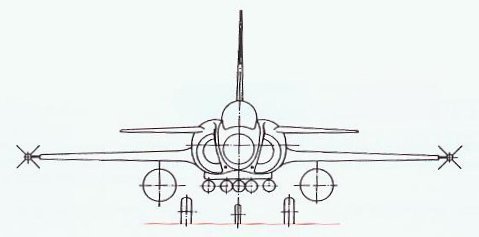

That is question. Seems to me like F404, but I am not 100% sure. There were warious propulsion proposals for Nammer:

1. SNECMA Atar 9K-50

2. General Electric F404

3. Volvo Flygmotor RM12 (in fact F404 with swedish afterburner)

4. Pratt and Whitney PW1120

5. SNECMA M53

For Sean: If I am right, than Nammer is combination of Kfir-C2/C7 and one of listed engine - this is called Nammer option 1. Nammer option 2 includes also Elta EL/M-2032 radar and some other equipment from cancelled Lavi.

- Joined

- 2 January 2006

- Messages

- 3,828

- Reaction score

- 5,133

frank said:I stumbled upon the Arie project online earlier. What info I found on it says it was essentally a drastically modified Kfir. The one pic I saw shows something that looks like more to it. Any 3 views anywhere? The same article mentions a proposed Super Kfir to be powered by a P & W F-100. Any further info on that one?

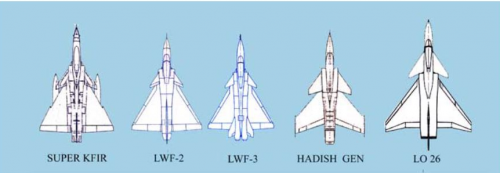

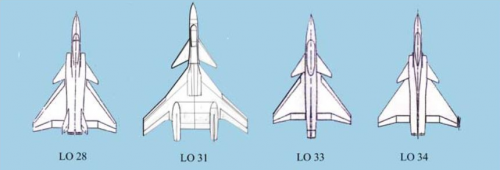

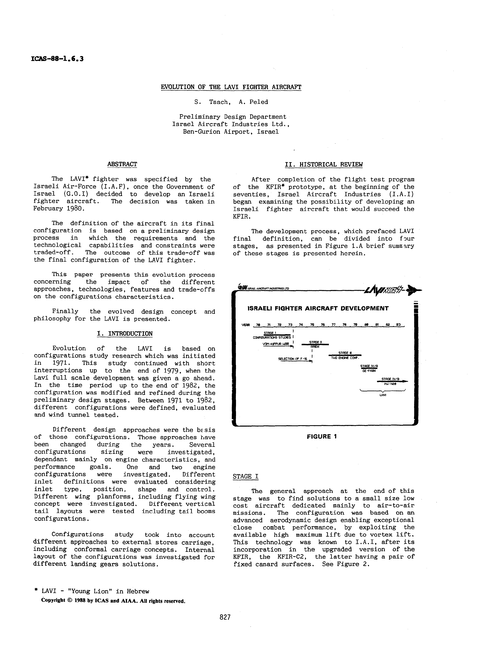

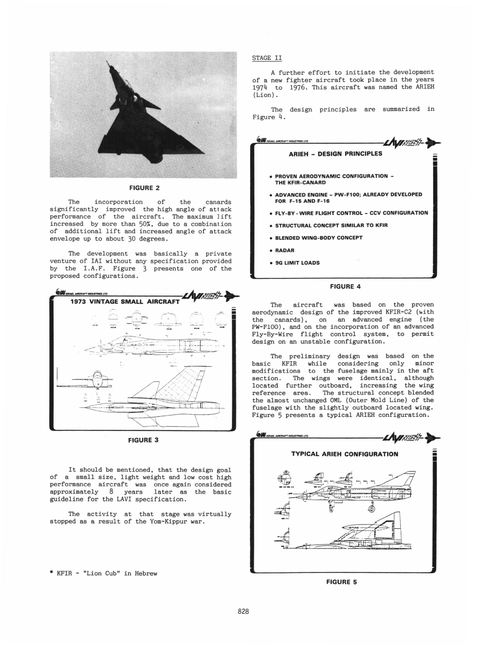

Here are some pictures of several configurations ...

Deino

Attachments

- Joined

- 29 September 2006

- Messages

- 1,794

- Reaction score

- 1,360

Web Page summary of Arie project: http://www.israeli-weapons.com/weapons/aircraft/arie/Arie.htm

Thanks, those are some of the ones I originally stumbled upon!

Deino said:frank said:I stumbled upon the Arie project online earlier. What info I found on it says it was essentally a drastically modified Kfir. The one pic I saw shows something that looks like more to it. Any 3 views anywhere? The same article mentions a proposed Super Kfir to be powered by a P & W F-100. Any further info on that one?

Here are some pictures of several configurations ...

Deino

- Joined

- 6 September 2006

- Messages

- 4,834

- Reaction score

- 9,460

Nammer Option 1 was designed for the F404, PW1120 or M-35 and could use re-worked Mirage III airframes, I guess for export purposes.

Nammer Option II used the EL/M-2032 or EL/M-2011 leightweight radar and other Lavi systems. The Volvo Flygmotor RM12 was the prime engne for Option 2. Length was 16m; 6260kg of weapons on nine hardpoints; normal and MTOW weights of 10,250 and 16,500kg; maximum sustained speed Mach 2.2 (Mach 0.2 faster than Kfir); 17,675m service ceiling and a lo-lo-lo attack radius of 1060km with two AAM, four CBU-58 and three droptanks.

Source: Air Forces of the World by Chris Chant, 1990

Nammer Option II used the EL/M-2032 or EL/M-2011 leightweight radar and other Lavi systems. The Volvo Flygmotor RM12 was the prime engne for Option 2. Length was 16m; 6260kg of weapons on nine hardpoints; normal and MTOW weights of 10,250 and 16,500kg; maximum sustained speed Mach 2.2 (Mach 0.2 faster than Kfir); 17,675m service ceiling and a lo-lo-lo attack radius of 1060km with two AAM, four CBU-58 and three droptanks.

Source: Air Forces of the World by Chris Chant, 1990

- Joined

- 3 June 2006

- Messages

- 3,094

- Reaction score

- 3,966

- Joined

- 27 December 2005

- Messages

- 17,751

- Reaction score

- 26,427

Attachments

- Joined

- 27 December 2005

- Messages

- 17,751

- Reaction score

- 26,427

http://www.israeli-weapons.com/weapons/aircraft/arie/Arie.htm

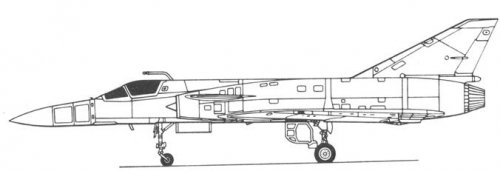

In 1974, an IAI team was set up to begin the Arie project. As no government approval had yet been received to produce it, the program was simply codenamed “R&D project”. Ovadia Harrari, who would later become head of the Lavi program, was to lead that endeavor.

The IAI decided to develop the Arie based on the technological knowhow acquired from the Kfir project, particularly from the Kfir-Canard program – the improved version. In fact, the first proposal which was put on hold by the Air Force, was to develop an aircraft to be named “Super Kfir” – a regular Kfir whose original J79 engine was replaced by an F100 model, the same as in early F-15/F-16s versions. That new engine would substantially increase the Super-Kfir's flying performance. However, due to the Air Force's strict specs requirements, a new draft was called for, in spite of the Kfir/Arie's visual similarities.

Over thirty different configurations were evaluated. The IAI tested several engine models, including the British Rolls- Royce RB-199, which powers the European Tornado aircraft. Soon, the options were reduced to just two. The F-100 single engine plane, or a twin-engine version.

The later, codenamed Light Weight Fighter-4 (LWF-4), was to be powered by two General-Electric F-404 engines as used in the F-18. “Looking at the different designs of the Arie, one can notice that it is an extensively modified Kfir” explains Harrari ,“ the aircraft is visually different, but its roots lay in the Kfir”.

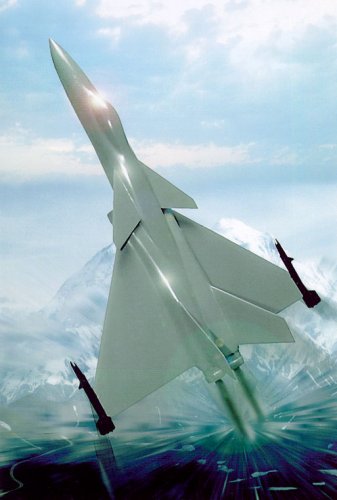

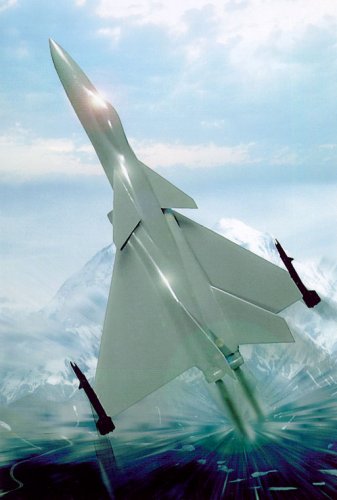

The new future fighter aircraft, which was now codenamed “Hadish” (innovative), could be described as a single seat light fighter, capable of reaching 2.4 Mach speed, a 75,000 ft altitude ceiling, with a 480 km combat radius. Armament: would have been a 30-mm cannon and medium range air-to-air missiles. Avionics would include a radar, a helmet sight and an integral electronic warfare system. In addition, the aircraft would have low optical and radar signatures. Even the US F-15 and F-16 could not match these features at that time.

The outstanding question: An air-to-air fighter, or an air-to-ground attack aircraft?

During its initial design phases, the 1973 Yom-Kippur war broke out, and the Israeli Air Force focused its attention on the battle proven air-to-air configuration concept, as air power and air superiority consist basically of air-to-air combat missions. Therefore, about 90 percent of the “Hadish” capabilities would be directed for air-to-air combat.

Technologies and Avionics

The Arie had several technological breakthroughs. It was designed to be the first Israeli aircraft to deploy digital fly-by-wire flight control system (at that time, cutting edge technology). This fly-by-wire concept, permitted the engineers to design an aerodynamically non-stable platform. Hence, they could achieve a small and highly maneuverable aircraft.

In the air-to-air version, to cope with enemy intruder aircraft, and keeping its air-superiority capabilities, the Arie would be equipped with advanced avionics and special ordnance systems: a highly sensitive Israeli radar capable of acquiring low-altitude flying targets. Advanced electro-optical systems would enable the Arie to locate ground targets at night.

Another breakthrough, was the pilot's option to use his helmet mounted sight, easing his combat workload. In the mid-70's these systems were nearly unheard of. It would take another ten years for the helmet mounted sight to become operational in any type of combat aircraft.

The Arie's cockpit resembles to a great extent that of the F-16's early versions. Besides the Head-up Display (HUD), a Monochromatic Display was mounted in the cockpit to display the radar's viewpoint.

The Pilot's view was close to 360º visibility– a life and death factor in air combats. This is now the normal design in both Western and Russian combat aircraft from the F-15 onwards.

The Arie's ordnance would include an improved 30-mm DAPA cannon, assorted air-to-air missiles, iron bombs, and precision guided ordnance. Max. military load is: 7 tons.

Although that aircraft was not meant to be a stealth aircraft, some basic stealth features were studied to give it the option to strike heavily fortified missile zones. This objective was based on the lessons learned during and after the 1973 Yom-Kippur war, when Israeli fighters had to face a huge number of SAMs. The Arie would also be equipped with an advanced Electronic-Warfare system produced by Israel , giving the pilot an early warning signal to lock on to enemy threats and jam them.

Studies were made to drastically reduce its radar signature, making it extremely difficult to be detected by enemy radar. For example, its bomb load was to be stowed inside a conformal ventral capsule, to reduce its radar cross section.

A Paper's Lion

According to the program timetable, the Arie's initial development phase should have been completed by mid 1979. Until then, the IAI would have to complete flight tests, select and define all the contractors.

By that year's end, an initial test flight was scheduled for the first of three prototypes.

By mid 1980, 10 pre-production aircrafts should be completed, with regular production to begin in the following two years. The Air Force should be receiving the first production Arie by the end of 1983. Delivery of 100 aircraft would be completed by the end of 1985.

Meanwhile, the IAF was leaning towards the US aircraft option. Rumors indicated that the USA would finally agree to sell Israel F-15s and F-16s. Finally, a decision was made to order the US aircraft. and scrap the Arie.

In August 1975, the IAF's chief, the (late) Gen. Benny Peled released a document defining the IAF's policy in relation to the Arie project. The document recommended the US F-15s and F-16s. Based on his assessment, the IAF began a procurement program of F-15s to be delivered by 1976. Moreover, it had been determined that the F-16 in principle answered Israel 's operational needs for an air superiority aircraft for the 80s. As a result of intense pressure on the IAF, Gen. Benny Peled decided to respond with a letter on May 10, 1976 , stating the reasons not to progress with the Arie: The US would agree to sell Israel F-16s. It had also been agreed that the US would sell Israel the F-100 engine, and there were not sufficient funds to keep the project moving.

“The fundamental knowledge that led to the development of the Lavi relied on the experience acquired from the “Hadish” and Arie”, says Gen. Lapidot, who created the Lavi project board, and commanded the Israeli Air Force by the time the project was canceled. “It can be definitely stated that the Arie, the Nesher and Kfir programs, added significantly to the development of the Israel Aircraft Industry (IAI), so that when we gave the “go ahead” for the Lavi, we already had a complete infrastructure in place and ready to work. In 1980, we decided to build a smaller version of the Arie. It is not by coincidence that it was named the Lavi. Lavi is a Lion (Arie), although a very much younger and smaller one”

- Joined

- 27 December 2005

- Messages

- 17,751

- Reaction score

- 26,427

http://www.airspacemag.com/military-aviation/the-lion-that-never-roared-79121223/#K0OLK3xRxDraWgrm.99It was the Israel Aircraft Industries’ most ambitious project: to design and develop a world-class fighter aircraft from scratch. The Arieh project, as it was known, was a concept design for a warplane on a par with the leading fighters of the day: the McDonnell Douglas F-15 and General Dynamics F-16.

Starting in late 1974, a small team of engineers at IAI toiled away on Arieh (“lion” in Hebrew), throwing around buzzwords like “digital fly-by-wire flight control system” and “reduced radar signature.” But at the time, design team leader Ovadia Harari recalls, “there wasn’t know-how in Israel to talk about this…. We didn’t have the knowledge.”

IAI was anxious to design and develop its own fighter because it had already succeeded in building two 1970s-era aircraft. France had sold Israel the Dassault Mirage III in the 1960s, but after the 1967 Six-Day War, Paris imposed an arms embargo on Israel. The first aircraft IAI built was Nesher (eagle), a version of the Mirage 5, made with licensed Dassault blueprints, tools, and jigs. From that came the Kfir (lion cub), an improved version with a different engine. Arieh was to be the third fighter in this lineage. But the Israel Air Force, which already had McDonnell F-4 Phantoms and Douglas A-4 Skyhawks, liked U.S. fighters. The F-15 joined Israel’s ranks in 1976, followed by the F-16 two years later.

Undaunted, IAI pressed ahead, using its own money to fund Arieh’s concept designs. Engineers began with what they knew: the single-engine Kfir’s aerodynamic shape, delta wing, and canards. As the design went through multiple iterations, Arieh’s shape began to change. “Arieh was a generic term,” Harari says, “like F-16, -17, -18, always beginning with F. Here it was Arieh-1, Arieh-2, Arieh-3…. There was a two-engine Arieh, an Arieh with two stabilizers, [another with] one stabilizer, engines under the fuselage, engines on the sides. All sorts of concepts.” Ultimately there would be more than 30 variations. With a budget of $2 million a year, engineers dealt only with external design, addressing elements like engines, weight, performance, and weapons. They conducted wind tunnel tests to study the aerodynamic properties of the various iterations.

While the Israel Air Force followed the work on Arieh, it was not supportive. The air force commander at the time, Major General Benny Peled, not only doubted IAI’s ability to pull off such a project, he also flatly rejected the need for such an aircraft. “It was clear to me that even if Israel Aircraft Industries succeeded in developing an advanced fighter aircraft, it would require a great amount of time and money, and therefore I believed it was a waste,” he told Israel Air Force magazine in 1998.

Peled was confident the F-15 and F-16 would meet his needs, and he was not interested in betting on a developmental project when he could buy proven aircraft. The only requirement Arieh would fulfill, he told the magazine, was IAI’s desire to build a homegrown fighter. Harari holds no grudge. “He [Peled] had to look after the IAF, not the defense industry’s well-being,” he says. If he were in Peled’s place, Harari adds, he might have done the same.

It became clear that if IAI were to build Arieh at all, U.S. assistance would be necessary. Despite its opposition to the project, the Israel Air Force joined a senior-level IAI and Ministry of Defense delegation on a trip to Washington, D.C., in 1979 to pitch the program to the Pentagon. But U.S. military officials, put off by the Israelis’ claims of being able to make a better and cheaper fighter than the U.S. aerospace industry could produce, turned them down.

Arieh, it seemed, was stuck on the drawing board. IAI even offered Israel’s then-ally Iran (and one other country that IAI to this day won’t disclose) a chance to join in the fighter’s development.

The Iranians were interested, and Harari was due to travel to Iran for discussions when the November 1979 Islamic revolution and the overthrow of the shah abruptly ended that plan. (Earlier, Israeli Defense Minister Ezer Weizman had met with his Iranian counterpart about the project; their meeting was revealed after the takeover of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, when Islamic students reassembled shredded secret documents and published them in 1982.)

With no funding and no customer, Arieh was essentially over, although IAI did maintain the program’s technology base. Weizman helped IAI obtain government funding to resuscitate part of the program. Selected from the Arieh portfolio for development was a small, single-engine design bearing a striking resemblance to the F-16.

archipeppe

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 18 October 2007

- Messages

- 2,431

- Reaction score

- 3,152

Cool....from Mirage to F-16 passing through F-18....

Thanks for sharing it, Paul.

Thanks for sharing it, Paul.

- Joined

- 27 December 2005

- Messages

- 17,751

- Reaction score

- 26,427

Thanks for sharing. Had seen some of these concepts before, but not all of them.PaulMM (Overscan) said:

Makes me look all the more forward towards that book on the Lavi that's scheduled to come out at year-end:

SlickDriver

ACCESS: Confidential

- Joined

- 20 June 2006

- Messages

- 161

- Reaction score

- 35

I got this over the New Year and thought appropriate for this forum.

www.israeldefense.co.il

www.israeldefense.co.il

In the summer of 1967, at the outset of the Six-Day War, the Government of France imposed an embargo on the supply of arms to Israel, and cancelled a transaction involving the supply of Mirage-5 fighter aircraft that were to be delivered to Israel as of December 1967. This embargo threatened Israel’s ability to defend itself, and the Israel Ministry of Defense consequently decided to assign the highest priority to the design and manufacture of a fighter aircraft – a “Blue and White” product by IAI.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Israel manufactured the Nesher fighter aircraft that were based on the French Mirage design. These aircraft were supplied to IAF until 1974. In the early 1970s, concurrently with the manufacture of the Nesher aircraft, an effort to characterize and design a more advanced fighter aircraft was initiated. The new aircraft was designated Kfir.

As far back as mid-1974, just before the development of the Kfir aircraft was completed and serial production began, IAI proposed to develop an advanced fighter aircraft designated Arie. In 1975, the commander of IAF in those days, Maj. Gen. Benny Peled, authorized the planning of the new aircraft. The aircraft was intended to be the spearhead of the IAF OrBat in the 1980s, alongside (and possibly instead of) the US-made F-15 and F-16. The design process of the Arie continued until 1979 through a total investment of US$ 40 million from IAI’s own capital. This aircraft was never actually developed.

The Birth of the Lavi

Over the course of 1979, the Israeli defense establishment reviewed the future OrBat of IAF. The decision makers faced three alternatives regarding the acquisition of fighter aircraft: to develop and manufacture an original Israeli fighter; to participate in the manufacture of a US-made fighter or to base the OrBat of IAF exclusively on aircraft acquired overseas.

In those days, the US government established a special team to consolidate the American position regarding the various alternatives for the new fighter aircraft of the IAF, including the alternative of jointly manufacturing a new fighter for IAF in the 1980s. The US team was intended to complete its work in early 1980. This proposal was not reviewed in depth, as stated by the report of the State Comptroller, who investigated the issue.

“The Lavi project began in the early 1980s. We were in the course of the IAF five-year acquisition plan,” recounts Maj. Gen. (res.) David Ivry. “I was the commander of IAF, Ezer Weizman was Minister of Defense, Raful (Rafael Eitan) was IDF Chief of Staff. We sought a replacement for the Phantom fighters. We never mentioned an Israeli-made aircraft. We regarded the Kfir as a platform that could be improved further.”

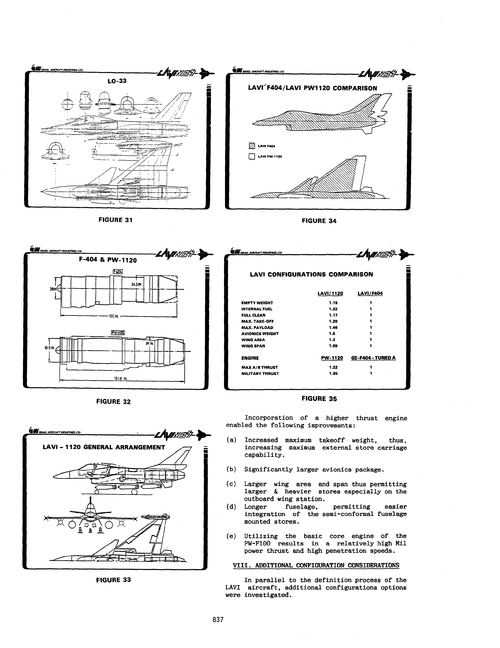

In that year, IAI came up with a proposal designated "Layout 33" – it was not yet designated "Lavi". The aircraft in that proposal, contrary to the Arie, was to be a single-engine, small and inexpensive design that would replace the ageing Kfir and Skyhawk aircraft that IAF intended to phase out. In terms of its position within the IAF OrBat, the Lavi was intended to be a "complementary" aircraft. It was not to be designed for air superiority missions but mainly for strike and airspace defense missions, to be employed alongside the more advanced F-15, F-16 and F-18 fighters. The decision to develop the Lavi aircraft was made in February 1980 by Ezer Weizman, who was Minister of Defense in those days.

“The general atmosphere in the State of Israel was that we should aspire for defense independence, including a locally-manufactured fighter aircraft,” Ivry continues. “(Originally) it was a very small aircraft that IAI claimed would replace the Skyhawk. That aircraft was too small and could not carry the munitions we wanted. My feeling was that we needed to acquire aircraft that offered a more substantial carrying capacity to a longer distance. I felt that our future challenges would involve longer distances. In the new characterization, we opted for a larger engine”.

Apparently, the problem with the Lavi project was not about technological know-how, but about money – and a lot of it. In December 1980, IAI submitted a long-term work plan and budget for the development effort which amounted to US$ 805.9 million (in 1980 prices). “Israel has no problem developing a fighter aircraft, neither back then, nor today. The problem is money,” says Ivry. “A country of 8 million citizens cannot develop a fighter aircraft. We are not the USA, Russia or China.

“There is one other point that needs to be clarified in this context. In reality, there is no such thing as defense or economic independence. Even the USA depends on (the supply of) titanium from Russia. No country is truly independent. You cannot do everything on your own. The USA is more independent than any other country, that much is true, but it is still relative. Even when you consider the Lavi aircraft project, the engine was American.

“The State of Israel should retain its qualitative advantage, and that can be achieved by upgrading certain elements of the platform, like upgrading the ECM (suit) and the Radar. The important thing is for us to have the necessary infrastructures – mainly laboratories. If we have such infrastructure in this country, we will be able to retain the primary elements that would provide us with the advantage on the battlefield.”

With regard to the Lavi project, Ivry reveals that no one had the money for it. “At the outset of the project, no one had calculated how much it would cost and where the money would come from. A larger aircraft costs more. The IDF (authorities) strongly opposed the Lavi project as they did not want anyone touching the defense budget,” says Ivry. “As far as I was concerned, as commander of IAF, I wanted a good aircraft. If they could provide me with an Israeli-made aircraft – excellent. Eventually, the money was raised by Moshe Arens, who managed to obtain assistance from the USA for the development of the aircraft. On average, the USA invested US$ 450 million in the Lavi project each year, of which US$ 200 million were invested in Israel, and all the rest in the USA.

“It is important to point out that the idea was not to shake off our dependence on the USA. Back then, the USA did not believe that we were able to develop a fighter aircraft (and that is why they gave us the money). (As far as they were concerned,) the money was intended to ‘let them play with it’. When the project began to shape up, the Americans realized that we were going toward highly advanced concepts. The American industries realized that we were going to have an aircraft that would be superior to the F-16 of those days, and started to oppose the project. The US industries could not understand why the USA financed an aircraft that would compete with the F-16.”

In 1982, a project administration was established at IMOD under Brig. Gen. Amos Lapidot, and the aircraft that started to shape up was not bad at all. Until the termination of the Lavi project in 1987, three prototypes were developed. “We made amazing progress with regard to the trial method. We established a large computer center that promptly analyzed all of the data received from the aircraft during the test flight and compared them to the planning, so we could make corrections during the actual test. In other words – we managed to do more in the context of the same flight. That shortened our trials significantly,” explains Ivry.

“We also developed a passive and active airborne Radar, electronic systems and even the pilot helmet currently manufactured by Elbit Systems was conceived in those days. These were all Israeli designs. Some of the manufacturing was carried out in the USA. We had a suitable conceptual infrastructure in Israel, but we lacked the laboratory infrastructure and other elements that were necessary for the development of the aircraft. The money for the Lavi project was invested in those elements, and served the State of Israel long after that project had been eliminated. For example – laboratories for the development of airborne Radars. The total investment in the Lavi project amounted to US$ 1.5 billion until the stage when the first two prototypes actually flew. That gave a tremendous boost to the defense industries.”

The Lavi flew for the first time in December 1986. In that year, the Americans began asking questions. Dov Zakheim, US Deputy Undersecretary of Defense for Planning and Resources, ruled out that Israel had underestimated the aircraft development cost, and that in effect its cost would reach US$ 22.1 million. Israel estimated the cost of the aircraft to be about US$ 17 million.

Overseas, Tom Jones, Chairman of the Board of Directors of Northrop, sent a letter to George Schultz, US Secretary of State, and to Casper Weinberger, US Secretary of Defense, claiming that it was ironic for the USA to financially support an Israeli rather than an American aircraft. In those days, Northrop was developing the F-20 aircraft. Both officials, who were swayed by the pressure exerted by the US defense industries, sent letters to Israeli Defense Minister Yitzhak Rabin.

“The Deputy Secretary of State arrived with all sorts of ideas in order to exert pressure to terminate the project. They spoke to us about additional funding for the Arrow, for the submarines and for other projects,” says Ivry. “There was also an offer for a price of US$ 14.9 million for the F-16. Naturally, they forgot to mention that those were 1978 figures. The Lavi turned out to be more expensive. Subsequently, the price of the F-16 rose to US$ 21 million. The game was about how many aircraft the IAF needed. The calculations were based on a minimum of 210 and a maximum of 300 (aircraft). The IDF said that if we wanted more money, the project should be defined as a national project and the money should not be taken from the defense budget.

“The Americans did not officially demanded that we terminate the project. They stated very subtly that we would not be able to implement the project, mainly owing to the financing problem. There were diplomatic letters with an implied threat between the lines that they would stop their aid. The letters were sent to Rabin, who was Minister of Defense in those days. Even before the year ended, IAI demanded an additional US$ 50 million per year for the project, on top of the American money. The funds were to come from the national budget, and that raised the threshold of the opposition to the project.”

The Termination of the Lavi Project

On August 30, 1987, by a single vote (12 against 11), the Shamir government decided to stop the Lavi project. “Admittedly, the project was terminated on the vote of (Minister of Health Shoshana Arbeli) Almozlino, but that was just the tip of the iceberg,” says Ivry. “Under the surface, several processes had drained into the same spot. If that had not happened at that time, the USA would have shut off the financing for the project some time later. Anyone who says that the project was terminated because of her (Minister Almozlino) misses the bigger picture.”

“In those days, about 5,000 people were working on the project directly. The IDF authorities said they could find employment for all those directly involved in the project. The State of Israel used some of the funds that continued to flow into the project from the USA to finance the severance pay. At that time, the entire defense industry experienced a violent jolt, not just IAI. During that period, the defense industry of Israel shrank almost by half, but became more business-oriented.

“The Lavi project propelled the industry to a higher league, with regard to the business thinking aspect as well as to the aspect of the R&D infrastructure established in Israel,” explains Ivry. “When we started out, I could not understand how we would manage to do it. There was no money. Toward the end of the project, I even had a chance to fly the Lavi, and it was a shame having to terminate the project. We truly achieved a very nice result. The Lavi made a contribution to the industry that has lasted to this day. Thanks to the Lavi project, the industry could undertake aircraft upgrading projects overseas, structured knowledge centers were established by the industries and various measures were developed that are still in service in IDF to this day.”

“Israel has no problem developing a fighter aircraft – the problem is money”

In the summer of 1967, at the outset of the Six-Day War, the Government of France imposed an embargo on the supply of arms to Israel, and cancelled a transaction involving the supply of Mirage-5 fighter aircraft that were to be delivered to Israel as of December 1967. This embargo threatened...

www.israeldefense.co.il

www.israeldefense.co.il

In the summer of 1967, at the outset of the Six-Day War, the Government of France imposed an embargo on the supply of arms to Israel, and cancelled a transaction involving the supply of Mirage-5 fighter aircraft that were to be delivered to Israel as of December 1967. This embargo threatened Israel’s ability to defend itself, and the Israel Ministry of Defense consequently decided to assign the highest priority to the design and manufacture of a fighter aircraft – a “Blue and White” product by IAI.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Israel manufactured the Nesher fighter aircraft that were based on the French Mirage design. These aircraft were supplied to IAF until 1974. In the early 1970s, concurrently with the manufacture of the Nesher aircraft, an effort to characterize and design a more advanced fighter aircraft was initiated. The new aircraft was designated Kfir.

As far back as mid-1974, just before the development of the Kfir aircraft was completed and serial production began, IAI proposed to develop an advanced fighter aircraft designated Arie. In 1975, the commander of IAF in those days, Maj. Gen. Benny Peled, authorized the planning of the new aircraft. The aircraft was intended to be the spearhead of the IAF OrBat in the 1980s, alongside (and possibly instead of) the US-made F-15 and F-16. The design process of the Arie continued until 1979 through a total investment of US$ 40 million from IAI’s own capital. This aircraft was never actually developed.

The Birth of the Lavi

Over the course of 1979, the Israeli defense establishment reviewed the future OrBat of IAF. The decision makers faced three alternatives regarding the acquisition of fighter aircraft: to develop and manufacture an original Israeli fighter; to participate in the manufacture of a US-made fighter or to base the OrBat of IAF exclusively on aircraft acquired overseas.

In those days, the US government established a special team to consolidate the American position regarding the various alternatives for the new fighter aircraft of the IAF, including the alternative of jointly manufacturing a new fighter for IAF in the 1980s. The US team was intended to complete its work in early 1980. This proposal was not reviewed in depth, as stated by the report of the State Comptroller, who investigated the issue.

“The Lavi project began in the early 1980s. We were in the course of the IAF five-year acquisition plan,” recounts Maj. Gen. (res.) David Ivry. “I was the commander of IAF, Ezer Weizman was Minister of Defense, Raful (Rafael Eitan) was IDF Chief of Staff. We sought a replacement for the Phantom fighters. We never mentioned an Israeli-made aircraft. We regarded the Kfir as a platform that could be improved further.”

In that year, IAI came up with a proposal designated "Layout 33" – it was not yet designated "Lavi". The aircraft in that proposal, contrary to the Arie, was to be a single-engine, small and inexpensive design that would replace the ageing Kfir and Skyhawk aircraft that IAF intended to phase out. In terms of its position within the IAF OrBat, the Lavi was intended to be a "complementary" aircraft. It was not to be designed for air superiority missions but mainly for strike and airspace defense missions, to be employed alongside the more advanced F-15, F-16 and F-18 fighters. The decision to develop the Lavi aircraft was made in February 1980 by Ezer Weizman, who was Minister of Defense in those days.

“The general atmosphere in the State of Israel was that we should aspire for defense independence, including a locally-manufactured fighter aircraft,” Ivry continues. “(Originally) it was a very small aircraft that IAI claimed would replace the Skyhawk. That aircraft was too small and could not carry the munitions we wanted. My feeling was that we needed to acquire aircraft that offered a more substantial carrying capacity to a longer distance. I felt that our future challenges would involve longer distances. In the new characterization, we opted for a larger engine”.

Apparently, the problem with the Lavi project was not about technological know-how, but about money – and a lot of it. In December 1980, IAI submitted a long-term work plan and budget for the development effort which amounted to US$ 805.9 million (in 1980 prices). “Israel has no problem developing a fighter aircraft, neither back then, nor today. The problem is money,” says Ivry. “A country of 8 million citizens cannot develop a fighter aircraft. We are not the USA, Russia or China.

“There is one other point that needs to be clarified in this context. In reality, there is no such thing as defense or economic independence. Even the USA depends on (the supply of) titanium from Russia. No country is truly independent. You cannot do everything on your own. The USA is more independent than any other country, that much is true, but it is still relative. Even when you consider the Lavi aircraft project, the engine was American.

“The State of Israel should retain its qualitative advantage, and that can be achieved by upgrading certain elements of the platform, like upgrading the ECM (suit) and the Radar. The important thing is for us to have the necessary infrastructures – mainly laboratories. If we have such infrastructure in this country, we will be able to retain the primary elements that would provide us with the advantage on the battlefield.”

With regard to the Lavi project, Ivry reveals that no one had the money for it. “At the outset of the project, no one had calculated how much it would cost and where the money would come from. A larger aircraft costs more. The IDF (authorities) strongly opposed the Lavi project as they did not want anyone touching the defense budget,” says Ivry. “As far as I was concerned, as commander of IAF, I wanted a good aircraft. If they could provide me with an Israeli-made aircraft – excellent. Eventually, the money was raised by Moshe Arens, who managed to obtain assistance from the USA for the development of the aircraft. On average, the USA invested US$ 450 million in the Lavi project each year, of which US$ 200 million were invested in Israel, and all the rest in the USA.

“It is important to point out that the idea was not to shake off our dependence on the USA. Back then, the USA did not believe that we were able to develop a fighter aircraft (and that is why they gave us the money). (As far as they were concerned,) the money was intended to ‘let them play with it’. When the project began to shape up, the Americans realized that we were going toward highly advanced concepts. The American industries realized that we were going to have an aircraft that would be superior to the F-16 of those days, and started to oppose the project. The US industries could not understand why the USA financed an aircraft that would compete with the F-16.”

In 1982, a project administration was established at IMOD under Brig. Gen. Amos Lapidot, and the aircraft that started to shape up was not bad at all. Until the termination of the Lavi project in 1987, three prototypes were developed. “We made amazing progress with regard to the trial method. We established a large computer center that promptly analyzed all of the data received from the aircraft during the test flight and compared them to the planning, so we could make corrections during the actual test. In other words – we managed to do more in the context of the same flight. That shortened our trials significantly,” explains Ivry.

“We also developed a passive and active airborne Radar, electronic systems and even the pilot helmet currently manufactured by Elbit Systems was conceived in those days. These were all Israeli designs. Some of the manufacturing was carried out in the USA. We had a suitable conceptual infrastructure in Israel, but we lacked the laboratory infrastructure and other elements that were necessary for the development of the aircraft. The money for the Lavi project was invested in those elements, and served the State of Israel long after that project had been eliminated. For example – laboratories for the development of airborne Radars. The total investment in the Lavi project amounted to US$ 1.5 billion until the stage when the first two prototypes actually flew. That gave a tremendous boost to the defense industries.”

The Lavi flew for the first time in December 1986. In that year, the Americans began asking questions. Dov Zakheim, US Deputy Undersecretary of Defense for Planning and Resources, ruled out that Israel had underestimated the aircraft development cost, and that in effect its cost would reach US$ 22.1 million. Israel estimated the cost of the aircraft to be about US$ 17 million.

Overseas, Tom Jones, Chairman of the Board of Directors of Northrop, sent a letter to George Schultz, US Secretary of State, and to Casper Weinberger, US Secretary of Defense, claiming that it was ironic for the USA to financially support an Israeli rather than an American aircraft. In those days, Northrop was developing the F-20 aircraft. Both officials, who were swayed by the pressure exerted by the US defense industries, sent letters to Israeli Defense Minister Yitzhak Rabin.

“The Deputy Secretary of State arrived with all sorts of ideas in order to exert pressure to terminate the project. They spoke to us about additional funding for the Arrow, for the submarines and for other projects,” says Ivry. “There was also an offer for a price of US$ 14.9 million for the F-16. Naturally, they forgot to mention that those were 1978 figures. The Lavi turned out to be more expensive. Subsequently, the price of the F-16 rose to US$ 21 million. The game was about how many aircraft the IAF needed. The calculations were based on a minimum of 210 and a maximum of 300 (aircraft). The IDF said that if we wanted more money, the project should be defined as a national project and the money should not be taken from the defense budget.

“The Americans did not officially demanded that we terminate the project. They stated very subtly that we would not be able to implement the project, mainly owing to the financing problem. There were diplomatic letters with an implied threat between the lines that they would stop their aid. The letters were sent to Rabin, who was Minister of Defense in those days. Even before the year ended, IAI demanded an additional US$ 50 million per year for the project, on top of the American money. The funds were to come from the national budget, and that raised the threshold of the opposition to the project.”

The Termination of the Lavi Project

On August 30, 1987, by a single vote (12 against 11), the Shamir government decided to stop the Lavi project. “Admittedly, the project was terminated on the vote of (Minister of Health Shoshana Arbeli) Almozlino, but that was just the tip of the iceberg,” says Ivry. “Under the surface, several processes had drained into the same spot. If that had not happened at that time, the USA would have shut off the financing for the project some time later. Anyone who says that the project was terminated because of her (Minister Almozlino) misses the bigger picture.”

“In those days, about 5,000 people were working on the project directly. The IDF authorities said they could find employment for all those directly involved in the project. The State of Israel used some of the funds that continued to flow into the project from the USA to finance the severance pay. At that time, the entire defense industry experienced a violent jolt, not just IAI. During that period, the defense industry of Israel shrank almost by half, but became more business-oriented.

“The Lavi project propelled the industry to a higher league, with regard to the business thinking aspect as well as to the aspect of the R&D infrastructure established in Israel,” explains Ivry. “When we started out, I could not understand how we would manage to do it. There was no money. Toward the end of the project, I even had a chance to fly the Lavi, and it was a shame having to terminate the project. We truly achieved a very nice result. The Lavi made a contribution to the industry that has lasted to this day. Thanks to the Lavi project, the industry could undertake aircraft upgrading projects overseas, structured knowledge centers were established by the industries and various measures were developed that are still in service in IDF to this day.”

ok ok

Trying to get Israel combat aircraft history in straight chronological order

- Mirage IIICJ (1962)

- Mirage V (1967)

- Nesher (1970)

- Kfir (1974)

- Arieh / Hadish (1973 - 1980)

- Lavi (1980 - 1987)

- Nammer (1987 - 1992)

Is that correct ?

the strange irony is that, bar the Lavi, they are all related to the Mirage III, one way or another.

Trying to get Israel combat aircraft history in straight chronological order

- Mirage IIICJ (1962)

- Mirage V (1967)

- Nesher (1970)

- Kfir (1974)

- Arieh / Hadish (1973 - 1980)

- Lavi (1980 - 1987)

- Nammer (1987 - 1992)

Is that correct ?

the strange irony is that, bar the Lavi, they are all related to the Mirage III, one way or another.

To clarify, the Mirage V was developed from the Mirage III to meet an Israeli specification, but never saw direct service in the IDF - thanks to a French embargo imposed after the1967 Six Day War.Archibald said:ok ok

Trying to get Israel combat aircraft history in straight chronological order

- Mirage IIICJ (1962)

- Mirage V (1967)

- Nesher (1970)

- Kfir (1974)

- Arieh / Hadish (1973 - 1980)

- Lavi (1980 - 1987)

- Nammer (1987 - 1992)

Is that correct ?

the strange irony is that, bar the Lavi, they are all related to the Mirage III, one way or another.

The Nesher, in turn, was a locally built copy of the Mirage V, assembled with assistance from Dassault (which violated the French arms embargo), but not from the engine manufacturer, Snecma. The Israelis had to resort to clandestine means (blueprints acquired by the Mossad) to acquire engines for the Nesher.

It was also not true that the Lavi was the first or only Israeli-built aircraft to deviate from their experience with the Mirage. The Aryeh represented a family of aircraft design concepts explored throughout the 1970s - one of which became the launch point for the Lavi. The author of the book published on the Lavi a little over a year ago included a sample of some of the Aryeh design concepts in his illustrations - which can also be found here:

Lavi Book: Illustrations

As I had previously indicated, the one thing that I would most have liked to have seen done differently with my recently published book on t...

Nesher was just another name for the Mirage 5. All were assembled from parts coming from France. Check out this plate on the Nesher #501 at hatzerim museum, Aerospatiale was building mirage parts for Dassault.

All that story about Neshers being build from plans given by Albert Frauenknecht was an covert story from Israel and french intels to hide the fact that Dassault and SNECMA still delivering Mirages and engines in kit to Israel after the "De Gaulle embargo".

At the time De Gaulle started the embargo, Israel was already switching to all US weapons, but Israel still had to use her Mirages and wanted upgraded ones. While France started to have other clients that would not have liked to know Dassault was still delivering Mirages to Israel while they were ordering some.

Check out these posts down this very interesting thread on acig , specially how the Kfir was mainly designed by Gene Salvay from Rockwell :

All that story about Neshers being build from plans given by Albert Frauenknecht was an covert story from Israel and french intels to hide the fact that Dassault and SNECMA still delivering Mirages and engines in kit to Israel after the "De Gaulle embargo".

At the time De Gaulle started the embargo, Israel was already switching to all US weapons, but Israel still had to use her Mirages and wanted upgraded ones. While France started to have other clients that would not have liked to know Dassault was still delivering Mirages to Israel while they were ordering some.

Check out these posts down this very interesting thread on acig , specially how the Kfir was mainly designed by Gene Salvay from Rockwell :

Attachments

- Joined

- 9 October 2009

- Messages

- 21,976

- Reaction score

- 13,638

Fighter-bomber project from around 1970.

- Joined

- 16 April 2008

- Messages

- 9,608

- Reaction score

- 14,503

The timing of this makes me skeptical that this is really an Israeli project. Possibly someone notionally mocking up a plane Israel might have wanted. But based on the timelines above, there was nothing going on in 1970 in Israel that would align with this design.

TinWing said:I am familar with this drawing of the Nammer proposal for the early 90s.

Does the drawing depict the F404 or the PW1120 engined version?

That is question. Seems to me like F404, but I am not 100% sure. There were warious propulsion proposals for Nammer:

1. SNECMA Atar 9K-50

2. General Electric F404

3. Volvo Flygmotor RM12 (in fact F404 with swedish afterburner)

4. Pratt and Whitney PW1120

5. SNECMA M53

For Sean: If I am right, than Nammer is combination of Kfir-C2/C7 and one of listed engine - this is called Nammer option 1. Nammer option 2 includes also Elta EL/M-2032 radar and some other equipment from cancelled Lavi.

First time I read the Nammer was proposed with the Atar 9K-50.

So, was the Atlas Cheetah C effectively the Nammer ? Remember reading it was build from Kfir airframes.

Wiki page on the Nammer talks about a prototype flying in March 1991 (or maybe they mix it with the Kfir C10, as it had the same avionics ?):

IAI Nammer - Wikipedia

"By 1991, 16 of each type were reported in service when the Cheetah D and E conversion lines closed. This same year, the first of the 38 Cheetah Cs commenced its conversion, the first such aircraft being rolled out during January 1993. All the Cheetah Cs entered service with 2 Squadron, which was also stationed at AFB Louis Trichardt."

from here:

Atlas Cheetah - Wikipedia

Last edited:

Neshers were Mirage 5s assembled by IAI from spares and engines from France.So the aircraft produced (or not produced) by IAI were:

Lavi

Nesher

Kfir

Arye

Nammer

Abir

Hadish

- Joined

- 27 December 2005

- Messages

- 17,751

- Reaction score

- 26,427

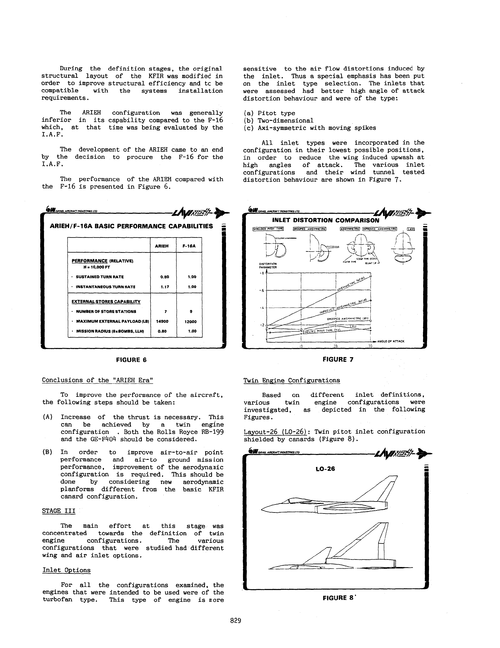

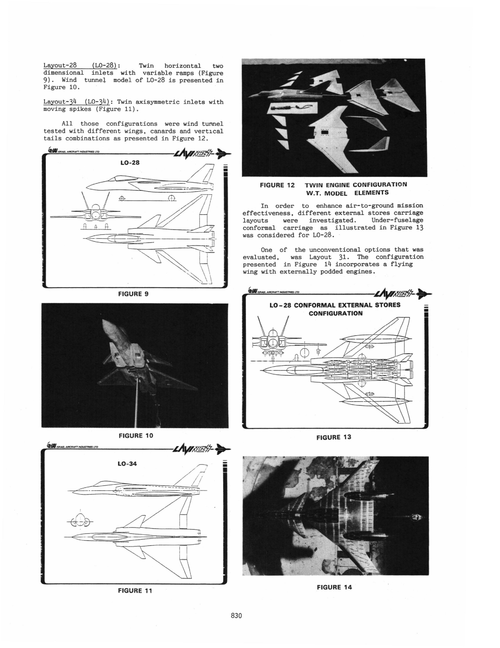

A detailed account of the Lavi design evolution can be found here:

Details of the canard and leading edge flaps here:

Details of the canard and leading edge flaps here:

NoBarrelRolls

"C'mon Mav! Do some of that pilot s#!t!"

I wrote a blog post about the Nammer a while ago, hope you find it useful.

https://nobarrelrolls.blogspot.com/2019/07/un-tigre-de-papel-el-iai-nammer.html

https://nobarrelrolls.blogspot.com/2019/07/un-tigre-de-papel-el-iai-nammer.html

- Joined

- 11 March 2012

- Messages

- 3,249

- Reaction score

- 3,179

Considering all the money invested by the USA, I have long wondered if Lavi was merely a USAF Research and Development program that Americans never expected to enter production. Grumman learned plenty about composites when building Lavi airframe components. Lear-Seigler learned about auto-pilots and stability augmentation systems, Sunstrand learned auxiliary power systems, etc.

Israel also learned how to build first-rate intercept radar that they retrofitted to a dozen other types of airframes.

Israel also learned how to build first-rate intercept radar that they retrofitted to a dozen other types of airframes.

- Joined

- 27 March 2006

- Messages

- 1,874

- Reaction score

- 1,621

I see in your blog, you state the following:I wrote a blog post about the Nammer a while ago, hope you find it useful.

https://nobarrelrolls.blogspot.com/2019/07/un-tigre-de-papel-el-iai-nammer.html

"As part of the sales effort, a unit of Kfir was modified (it was Kfir C2 serial number 979) as a proof of concept. This aircraft made its maiden flight on March 21, 1990 and was equipped with a Snecma Atar 9K50. This prototype was easily distinguishable from the other Kfir, by having a longer nose and lacking the additional air intake at the base of the drift."

Are there any pictures of this modified Kfir C2?

The only pics I can find online of Kfir 979 show the standard Kfir nose and air cooling intake at the base of the fin.

- Joined

- 27 December 2005

- Messages

- 17,751

- Reaction score

- 26,427

A detailed account of the Lavi design evolution can be found here:

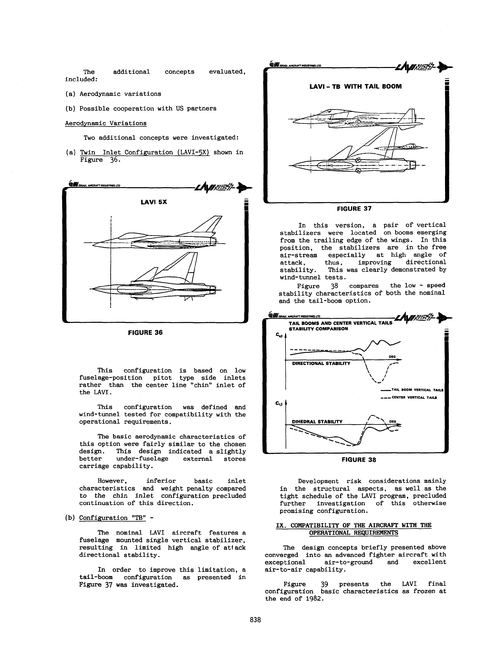

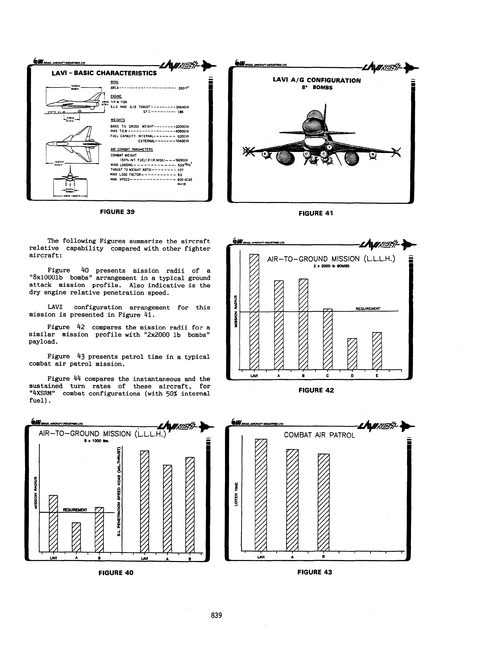

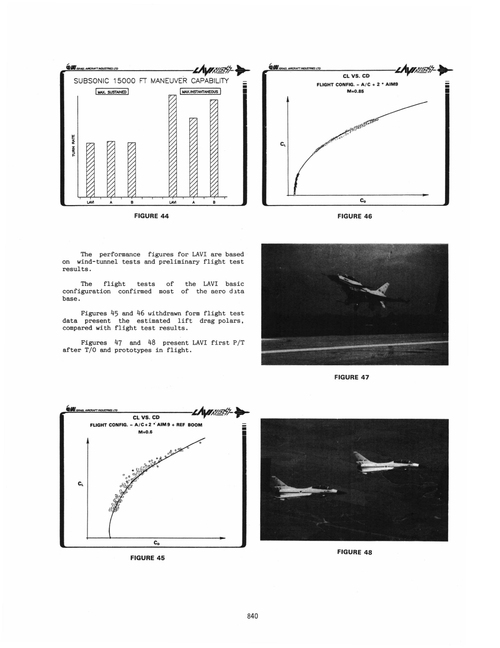

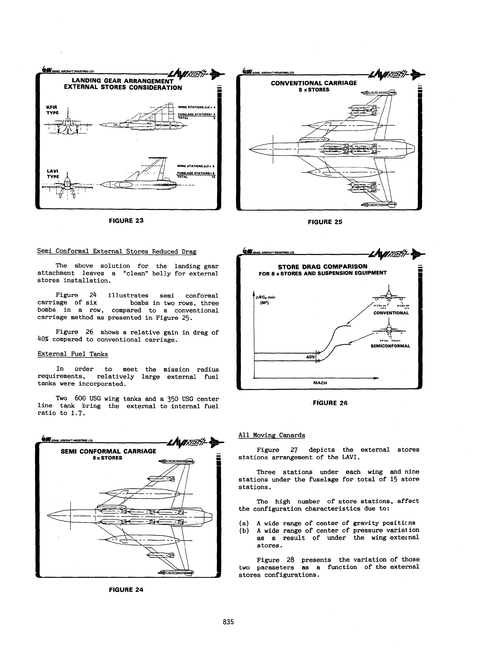

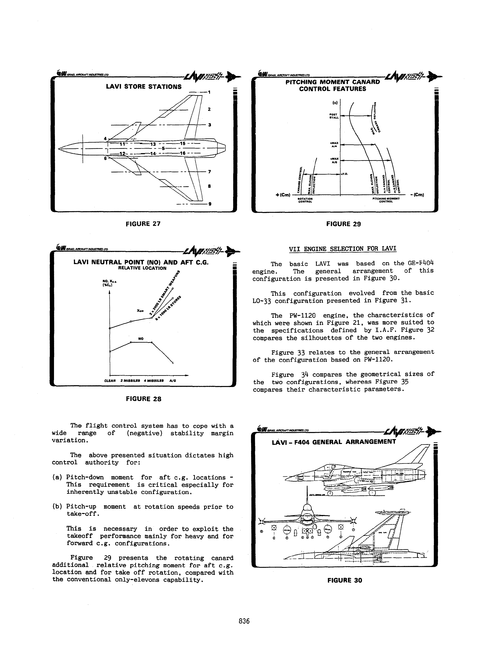

Here's the first 10 pages of the article.

Attachments

-

ICAS-88-1.6.3_Page_01.png136.5 KB · Views: 348

ICAS-88-1.6.3_Page_01.png136.5 KB · Views: 348 -

ICAS-88-1.6.3_Page_02.png804.7 KB · Views: 321

ICAS-88-1.6.3_Page_02.png804.7 KB · Views: 321 -

ICAS-88-1.6.3_Page_03.png118.7 KB · Views: 320

ICAS-88-1.6.3_Page_03.png118.7 KB · Views: 320 -

ICAS-88-1.6.3_Page_04.png873.5 KB · Views: 303

ICAS-88-1.6.3_Page_04.png873.5 KB · Views: 303 -

ICAS-88-1.6.3_Page_05.png121.9 KB · Views: 275

ICAS-88-1.6.3_Page_05.png121.9 KB · Views: 275 -

ICAS-88-1.6.3_Page_06.png107.9 KB · Views: 247

ICAS-88-1.6.3_Page_06.png107.9 KB · Views: 247 -

ICAS-88-1.6.3_Page_07.png129 KB · Views: 245

ICAS-88-1.6.3_Page_07.png129 KB · Views: 245 -

ICAS-88-1.6.3_Page_08.png130.3 KB · Views: 251

ICAS-88-1.6.3_Page_08.png130.3 KB · Views: 251 -

ICAS-88-1.6.3_Page_09.png101.2 KB · Views: 260

ICAS-88-1.6.3_Page_09.png101.2 KB · Views: 260 -

ICAS-88-1.6.3_Page_10.png102.4 KB · Views: 276

ICAS-88-1.6.3_Page_10.png102.4 KB · Views: 276

NoBarrelRolls

"C'mon Mav! Do some of that pilot s#!t!"

Hi Kaiserbill, unfortunatly, I wasn’t able to retrieve a picture of this prototype.I see in your blog, you state the following:I wrote a blog post about the Nammer a while ago, hope you find it useful.

https://nobarrelrolls.blogspot.com/2019/07/un-tigre-de-papel-el-iai-nammer.html

"As part of the sales effort, a unit of Kfir was modified (it was Kfir C2 serial number 979) as a proof of concept. This aircraft made its maiden flight on March 21, 1990 and was equipped with a Snecma Atar 9K50. This prototype was easily distinguishable from the other Kfir, by having a longer nose and lacking the additional air intake at the base of the drift."

Are there any pictures of this modified Kfir C2?

The only pics I can find online of Kfir 979 show the standard Kfir nose and air cooling intake at the base of the fin.

If I am not mistaken, that was stayted in one of the magazines, I took as reference.

- Joined

- 27 December 2005

- Messages

- 17,751

- Reaction score

- 26,427

A detailed account of the Lavi design evolution can be found here:

Last 5 pages

Attachments

- Joined

- 3 September 2006

- Messages

- 1,475

- Reaction score

- 1,472

That Kfir-with-9K50 idea was the proposed Kfir C-9 to Argentina. It was cancelled.I see in your blog, you state the following:

"As part of the sales effort, a unit of Kfir was modified (it was Kfir C2 serial number 979) as a proof of concept. This aircraft made its maiden flight on March 21, 1990 and was equipped with a Snecma Atar 9K50. This prototype was easily distinguishable from the other Kfir, by having a longer nose and lacking the additional air intake at the base of the drift."

I'd be surprised if it ever happened. As of Aug 2010, Kfir 979 looked like this:Are there any pictures of this modified Kfir C2?

The only pics I can find online of Kfir 979 show the standard Kfir nose and air cooling intake at the base of the fin.

979 | IAI Kfir C2 | Israel - Air Force | 4x6zk-AirTeamImages | JetPhotos

979. IAI Kfir C2. JetPhotos.com is the biggest database of aviation photographs with over 6 million screened photos online!

It would have to have been butchered back to its original shape...

Last edited by a moderator:

- Joined

- 27 March 2006

- Messages

- 1,874

- Reaction score

- 1,621

Dan_inbox.... yup, I saw that pic of 979 in the Israeli Air force museum when looking around.

I too cannot believe they would modify it to fit an 09k50, and then remodify it back again for display. It makes no sense... expensive and butchered.

Hence why I asked the question. I was hoping perhaps the serial number was mistyped.

I too cannot believe they would modify it to fit an 09k50, and then remodify it back again for display. It makes no sense... expensive and butchered.

Hence why I asked the question. I was hoping perhaps the serial number was mistyped.

Similar threads

-

The M53 connection: France, South Africa, Israel, and... China

- Started by Archibald

- Replies: 12

-

SAC News 50 Years Ago this month from the Air Force Association

- Started by bobbymike

- Replies: 1

-

Ekco and the Fairey Fireflash

- Started by overscan (PaulMM)

- Replies: 7

-

The Development of the Admiral Class Battlecruisers

- Started by Tzoli

- Replies: 6

-