First, let's look at the evolution of the Luftwaffe bomber force before looking at where it stood in the Summer of 1940.

Background to German Re-Armament

While Hitler denounced Versailles in the Reichstag on 17 May 1933, it took until 26 February 1935 for the existence of the Luftwaffe to be acknowledged, followed by the blatant violation (and death) of Versailles on 16 March 1935 when German conscription was announced.

Until March 1935, almost all German military work had to be done in secret. Where it couldn't be hidden (airplanes) a weak, semi-plausible civilian rationale (civilian airliner or experimental racer) was used to keep the Big Two (France and Britain) off of Germany's back.

First Generation Bombers - The Secret Ones -- these planes were designed and entered service when the Luftwaffe didn't officially exist.

Junkers 52 Series

Ju 52/3mg3e: 1,000 kg (2,205 lbs) to 310 mile (500 km) radius

The Ju-52 was designed beginning in 1930, and following several years of production for civilian airlines, a secret militarized variant, the

Ju 52/3mg3e was developed and ordered pending arrival in quantity of a "purpose" built bomber in the Dornier 11 series. Despite this, the Ju-52 ended up equipping the majority of the early Luftwaffe bomber units.

Dornier 11 Series (Do-11/Do-13/Do-23)

Do-11 (1932-?): 1,000 kg (2,205 lbs) to 298 mile (479.5 km) radius

Do-23 (1934-1936): 1,000 kg (2,205 lbs) to 420 mile (675.9 km) radius

These aircraft were developed from the earlier Do P (1930) and Do Y (1931) prototypes; with the Do F (Do-11) prototype being built in Switzerland. About 141 Do-11 and 273 Do-23 were delivered (the few Do-13 built being converted to Do-23s).

The first bomber unit was the Behelfsbombergeschwader (BehBG) or "Auxiliary Bomber Group"; and to maintain cover, officially it was in public sources, the Verkehrsinspektion der DLH (Traffic Inspectorate of Deutsche Lufthansa).

Later in November 1933, the Deutsche Reichsbahn (German State Railway) replaced two of its night trains with air freight service flown by Lufthansa. In reality, these were flown on Do-11s crewed by Behelfsbombergeschwader pilots, gaining experience in night flying.

Second Generation Bombers - The "Mail" Planes -- the second generation, while still needing a "cover" as a fast passenger/mail plane, could be more blatant in how they skirted the line between civilian and military purposes.

Dornier 17 Series

Do-17E-1 (?): 750 kg (1,650 lbs) to 310 mile (498.8 km) radius

Do-17M-1 (?-1941): 1,000 kg (2,205 lbs) to 310 mile (498.8 km) radius

Do-17Z-2: (1940-?): 1,000 kg (2,205 lbs) to 210 mile (337.9 km) radius

The Do-17 was designed to meet a 1933 six-passenger mail plane specification by Lufthansa -- after three prototypes were evaluated by Lufthansa in 1935, they were returned to Dornier as being insufficient for the airline's needs. The next year however, the first bomber version, the Do-17E-1 was delivered in late 1936.

There were three major bomber versions, the -E, -M, and Z; and in each, they were cramped for the crew -- the type was simply just too small to be a realistic medium bomber.

When they redesigned the Do-17 to have a slightly larger nose with extra guns for the bombardier, the added weight reduced bombload on the Do-17Z-1 to 500 kg. Adding more powerful engines (+100 more HP each) restored the bombload to 1,000 kg on the production Do-17Z-2, but reduced the combat radius to 210 miles.

In a final postscript, production limitations forced a shift from BMW inline engines on the E to radial engines in the M and Z variants -- the Reichluftministry (RLM) needed all the inline engines for the fighter force (Bf-109/110).

The Ju-86 Series

Ordered to the same 1934 specification - high speed twin engined 10 passenger aircraft - as the He-111, the Ju-86 was generally inferior to the He-111 in Spanish Civil War experience. Despite a single gruppe (III KG 1) participating in the invasion of Poland, the Ju-86 was retired from active service shortly afterwards, going to training schools.

Some were converted to Ju-86P high altitude high altitude reconnaissance aircraft and bombers in 1941-1942.

The Early He-111 Series

He-111P/H (1940): 500 kg (1,102 lbs) to 400 mile (645 km) radius

He-111P/H (1940): 1,000 kg (2,205 lbs) to 300 mile (483 km) radius

Heinkel took the earlier single-engine He-70's wing and tail assembly and scaled it up to a larger twin-engine design, which first flew in May 1935, followed by civilian passenger service with Lufthansa (He-111C in 1936) and military service (He-111B in late 1936).

The He-70 and He-111 lineage is clear in this image

Civilian He-111 Cutaway

Civilian He-111 Interior, looking forward, you can see the four seat "smoking" compartment (aka bomb bay).

Civilian He-111 Interior, looking rear

Because of the need to masquerade as a civilian aircraft until 1935, the He-111 was forced to make compromises to avoid being blatantly a bomber, the same as the Dornier 17.

In the case of the He-111, they had to make the fuselage narrow instead of wide; which forced an odd internal bomb bay arrangement in order to fit the maximum number of bombs inside.

This was the ESAC 250 cell (Elektrische-Senkrecht-Aufhängung für Cylinderbomben), which translates as Electrical Vertical Suspension for Cylinder Bombs. In the ESAC 250 cell, bombs were stored nose up, which led to inaccuracy issues; but it couldn't be helped.

ESAC on early (stepped nose) He-111

Like the Dornier 17, the He-111 had it's development altered by the need for engines for fighters.

In late 1939, the He-111 was in production under two variants -- the -111P with the DB 601 engine, and the -111H with the Jumo 211 engine. Other than the engines, they were effectively the same. In 1940, the RLM killed the He-111P in favor of the He-111H because they needed the DB-601s for Bf-109 and Bf-110 production.

The late He-111 Series - or why the He-111 stayed in production for so long.

He-111H-16 (1942): 1,000 kg (2,205 lbs) to 640 mile (1029.98 km) radius.

From the He-111H-4 onwards, external bomb racks were fitted. These racks blocked the bomb bay, so most aircraft with the external bomb racks had the bomb bay space filled with a 835 liter (221 US gallon) fuel tank; giving it nearly 200 more miles of combat radius and making the He-111 competitive with the Ju-88; and the He-111 could more easily carry a wider load of external bombs than the Ju-88.

Diagram showing the location of the major fuel tanks and the bomb bay tank.

He-111 bomb rack approved configurations were:

4 x 250 kg + 1 x 500 kg (1,500 kg total)

or

5 x 250 kg (1,250 kg total)

or

3 x 1000 kg (3,000 kg total)

or

3 x 500 kg (1,500 kg total)

or

2 x 1800 kg (3,600 kg total)

or

1 x 2500 kg

or

2 x 45cm (17.7") F5b Torpedoes (812 kg each, 1,624 kg total)

Third Generation Bombers -- The Wünderplane and the Ural Bomber

The Ural Bomber(s)

In 1935, the Luftwaffe issued a specification for a

Langstrecken-Grossbomber (Long-Range Heavy Bomber) to Dornier and Junkers.

The specification was for 1,100 kg (2,425 lb) of bombs to 2,500 km (1,553 miles); later revised to 1600 kg (3,527 lb) for 2,000 km (1,242 miles); which would give it a combat radius of about 435 miles (700 km).

Both corporations produced prototypes (Do-19 and Ju-89) with flight testing in October-December 1936; before the RLM cancelled the Uralbomber program on 29 April 1937.

The reason for cancellation was that following the June 1936 death of Walther Wever in a plane crash, his replacement - Albert Kesserling - argued that Germany couldn't spend twice the engines, double the fuel consumption, and 2.5 times the amount of alumium to get a bomber that could carry the same bombload as a smaller medium bomber -- and the smaller medium bomber could cover about 70% of the targets that the Uralbomber could.

This was very important given Germany's strategic considerations at the time -- they had to rapidly build up a force of combat aircraft capable of deterring the Big Two (France & Germany); while facing an increasing amount of resource constraints.

Ernst Udet himself told Ernst Heinkel this in 1938:

"In [the] future, there will be no multi-engined bombers that cannot attack in a dive. The He 111 is the last horizontal bomber. Thanks to its accuracy on target, a medium-sized, twin-engined aircraft that delivers its 1,000 kg bomb-load on target in a dive has the same effect as a four-engined giant bird that carries 3,000-4,000 kg of bombs in horizontal flight but can only drop them inaccurately."

"We do not need the expensive machines that gobble up so much more material than a twin-engined dive-bomber. Junkers has the first twin-engined dive-bomber ready, the Ju 88. We can build two or three of this type with the same amount of material required for a four-engined job, and still achieve the same bombing effect. Jeschonnek too is fully enthusiastic. By building these large-size Stukas which cost less in materials, we can produce the number of bombers demanded by the Führer!"

We can however extrapolate what might have been for the Uralbomber if it had been given full development from the examples of the He-111 and B-17:

He-111P/H (1939): 1,000 kg (2,205 lbs) to 300 mile (483 km) radius

He-111H-16 (1942): 1,000 kg (2,205 lbs) to 640 mile (1029.98 km) radius.

2.1x combat radius increase

B-17B (1939): 1,088.6 kg (2,400 lbs) to 448 mile radius.

B-17G (1945): 1,814.3 (4,000 lbs) to 700 mile radius.

1.5625x combat radius increase

Lets average it to a 1.831x radius increase; and we end up with a fully developed Uralbomber radius of 800~ miles.

The Ju-88

The Ju-88 design began in August 1935 with a

Schnellbomber specification that called for a three-seat, twin engined bomber with 800 to 1000 kg bombload, a maximum speed of 500 km/hr and with no more than 30,000 man hours required to build each aircraft.

There were five competitors for this specification -- Bf-162, Hs-127, Ju-85 (essentially a twin-tailed Ju-88), Ju-88, He-119 -- and all except the Ju-85 received prototypes.

The Bf-162 was killed early on in order to let Messerschmitt to concentrate on Bf-108/109/110 production; while the others were killed due to engines. The Ju-88 used Jumo 211s; while the others used variants of Daimler-Benz engines, which were needed for Bf-109/110 production.

Despite gaining a lot from being the first Luftwaffe bomber that could be designed in the open; a lot of time was lost thanks to various RLM inconsistencies, which changed it from a three-man lightly armed fast bomber into a four-man heavily armed dive bomber.

The design pushed the strate of the art of stressed skin construction forcing a lot of "don't do this" reminders in the early Ju-88 manuals. One also wonders whether the fact that one of it's chief designers -- Alfred Gassner -- was an American citizen who returned to the US after the first prototype was completed had anything to do with this.

I've run across differing states for combat radius for the Ju-88.

The German Air Force, 1933-1945: An Anatomy of Failure by Matthew Cooper states:

Ju-88A-1: 1,000 kg (2,205 lbs) to 550 mile (885.1 km) radius

Ju-88A-1: 1,500 kg (3,380 lbs) to 250 mile (402.3 km) radius

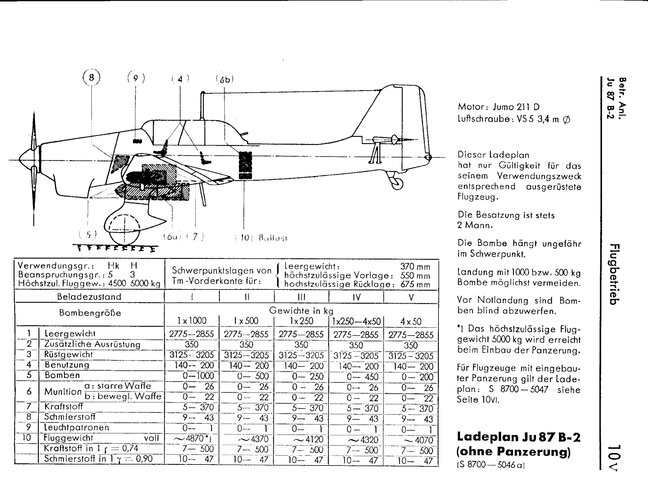

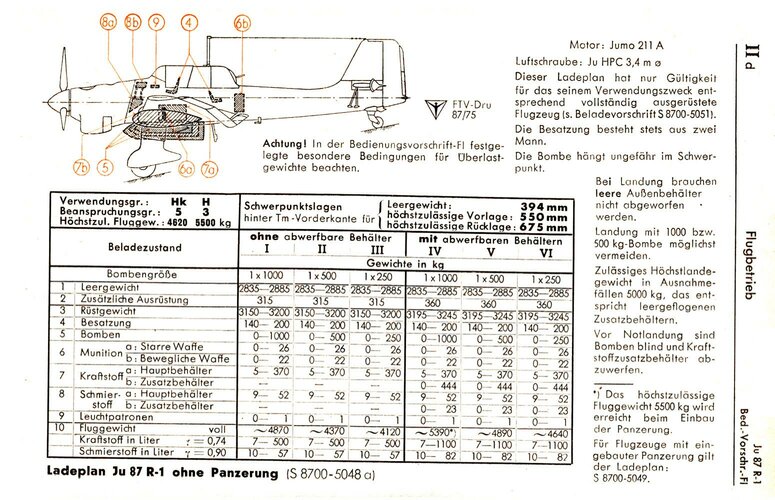

while this German Briefing Slide (

IMAGE A/

IMAGE B) claims different ranges (convert to combat radius by multiplying from a range of 0.305 to 0.40).

I believe that this is due to Ju-88 units in the Battle of Britain being limited to Rüstzustand A (1,680L Wing Fuel Only), while the chart by Junkers shows best possible ranges with the most optimal configurations for future Ju-88 development, including:

Rüstzustand B (1,680L Wing Fuel + 1,222L forward bomb bay aux tank)

Rüstzustand C (1,680L Wing Fuel + 1,222L fwd b.bay aux tk + 680L aft b.bay aux tk)

Rüstzustand C+ (1,680L Wing Fuel + 1,222L fwd b.bay aux tk + 680L aft b.bay aux tk + two 900L wing drop tanks)

Using the Junkers chart and a 0.35x multiplier, we get for late-war Ju-88 units capable of utilizing all possible combinations of Rüstzustand with beefed up landing gear and larger tires:

Ju-88A-4: 500 kg (1,102 lbs) to 800 mile (1286 km) radius

Ju-88A-4: 1,000 kg (2,205 lbs) to 630 mile (1014 km) radius

Ju-88A-4: 1,500 kg (3,307 lbs) to 508 mile (818 km) radius

Ju-88A-4: 2,400 kg (5,291 lbs) to 273 mile (439 km) radius

These numbers line up with claims that the Ju-88 could carry a "one ton bomb load to a radius of 600 miles" on the Eastern Front.

Fourth Generation Bomber -- Bomber A

On the very same day that Walter Wever died (3 June 1936), the RLM instructed Blohm & Voss, Heinkel, Henschel and Junkers to start developing a heavy bomber (with dive bombing capability); with studies due August 1936.

Bomber A specifications were for a 500 km/hr top speed, 5,000 km range and a three man crew (Pilot + Co-Pilot/Gunner + Radio Operator/Gunner), utilizing remote controlled 13mm MG131 turrets.

Heinkel's P.1041 proposal for Bomber A (500 kg payload to 2500 km range) was accepted and following mockup inspections; the official RLM designation of He-177 was assigned in late 1937 to the program, and three operational ranges were set (Nahbomber, Mittelbomber, and Fernbomber).

In early 1938, the RLM changed the specifications to 1,000 kg payload to 6,700 km (4,163 miles) and a crew of four, and no delivery of prototypes took place, because no DB606 engines were available -- only two prototype DB606 engines were available for the privately developed He-119 high speed aircraft venture, with no serial production engines available.

Heinkel proposed to the Luftwaffe General Staff that two of the six contracted He-177 prototypes be fittede with four separate Jumo 211 engines -- this was rejected on the grounds that this would eliminate the dive bomber capability; before it was accepted on 17 November 1938 that the He-177 V3 and V4 would have four engines due to the powerplant situation.

The long delay in DB606s showing up continued into 1939, to the point that Heinkel began actively searching for alternative powerplants, and getting Udet's approval for the following prototype schedule:

He-177 with DB-606: By end of August 1939

He-177 with Jumo 212 (two Jumo 211's coupled): By end of January 1940

He-177 with BMW 802 radials (two BMW 801s coupled): By mid-April 1940

When Udet visited Heinkel in April 1939, the staff once again raised discussion with him about the four-engined He-177 concept; but apparently this was turned down as well.

To make things short, there were endless delays, due to lack of engines, then constant problems with the engines and other technical issues:

He-177 V1 Prototype First Flight: 9 November 1939 - 1.4 years delay

He-177A-0 Pre-Production Delivery: 19 May 1941 - 2.6 years delay

The specifications at the time for the A-0 series were:

Rüstzustand A (

Nahbomber / Short Range Bomber) (8800L fuel)

2000 km (1243 miles) range - 7,000 kg bombs (435 mile radius est.)

Rüstzustand B (

Mittelbomber / Medium Range Bomber) (10,730L fuel)

3000 km (1864 miles) range - 4,000 kg bombs (652 mile radius est.)

Rüstzustand C (

Fernbomber / Long Range Bomber) (12,660L fuel)

5000 km (3107 miles) range - 1,000 kg bombs (1,087.45 mile radius est.)

Amusingly enough, to switch from Rüstzustand to Rüstzustand required special parts kits and install time; it wasn't just enough to put in auxiliary fuel tanks or drop tanks. In any case this was the best the He-177 could offer -- every successive version lost range, whether through added weight or fuel loss from more defensive armament and strengthening the wing.

Operationally, the He 177 never really quite got there -- there was a deployment of them in Stalingrad with I/FKG 50 in January 1943 as cargo aircraft for the Stalingrad Airlift, as well as maritime patrol aircraft with guided weapons, but their first real operational debut as a bomber was with KG 1 in Summer 1944.

KG 1 was deployed to Prowehren (54.766667, 20.396667) and Seerappen (54.7494, 20.2906), both in East Prussia -- now part of Kaliningrad Oblast.

From those bases, the He-177s executed high altitude daylight attacks against Soviet rail hubs; among them being:

20 July 1944: All 87 of KG 1's operational bombers flew against the Velikiye Luki railroad station, some 400~ miles distant. They apparently flew so high that Russian fighters couldn't easily intercept and they caused a serious amount of damage to the station and town for no losses. Another strike was also apparently made on the Kalinkovichi rail yards, also some 400 miles distant.

22 July 1944: Brest-Litovsk some 220 miles distant was bombed with "up to 20 aircraft"; destroying the HQ of the Russian 80th Rifle Corps, killing Major General I.L. Ragulia.

23 July 1944: Molodechno was bombed, some 270~ miles distant; large fires and explosions were reported.

Their last mission against Russian troop columns was made on 25 July, after which KG 1's war was effectively over.

Further He-177 Development

On 15 September 1942, Goering finally removed the dive bombing requirement, allowing development of the four-engined He-177 to seriously start, some four years late.

One of the few photographs of a He-177B prototype in existence.

Range for the various proposed four engined versions averaged about 4,400 km (2,734 miles); some 400 km less than the twin engined He-177A-5's 4,800 km; giving it a maximum radius of action of 1,540 km (957 miles).

By late summer 1943, the four-engine He-177B-5's development schedule was estimated as:

First Prototype Aircraft: 1 April 1944

First Production Aircraft: March 1945

As you can see... it's too little, too late.

The most amusing thing about the whole He-177 mess is if you know anything about the Avro Model 679 Manchester, you'll see a lot of similarities.

The Manchester was to be a twin engined medium bomber that could make shallow dive-bombing attacks; and it was powered by two Rolls Royce Vulture engines, which were two Peregrine engines joined with a new crankshaft, forming a X-24 engine with 2600 cubic inches displacement and 1,780 hp.

Unlike Germany, the British didn't waste any time in shifting over to a four engined version (Lancaster) with conventional powerplants -- the Manchester flew operationally on 24 February 1941; with the Lancaster's debut a little bit more than a year later (372 days) on 3 March 1942.

Fifth Generation Bombers - Bomber B

The Bomber B Specification was issued by RLM on July 1939 to Arado, Dornier, Focke Wulf and Junkers for a twin engine high altitude pressurized medium bomber to replace the Ju-88 and He-111.

It was to have a top speed of 600 km/hr and carry a 4,000 kg (8,420 lb) bombload to any part of Britain from French or Norwegian bases, implying a combat radius of about 700 miles and a range of 2000 miles (3,218 km).

Junkers' and Focke-Wulf's designs were selected for development, but Bomber B was cancelled in June 1943 due to both a lack of resources and the inability of German industry to deliver powerplants capable of reaching the 2,466 hp power levels needed to make the "Bomber B" spec work.

Sixth Generation Bombers - Dirty Paper!

In early 1942, the Germans did a survey on what their aviation industry had with the capability to strike at the US from bases in the Azores; with the completed plan being given to Goering on 12 May 1942.

At that point, it was all pretty much dirty paper and a few prototypes; with no realistic chance of them actually entering service.

LOOKING AT AIRFIELDS

With all that out of the way; let's look at realistic basing options for a strategic bombardment campaign against England --

GOTT STRAFE ENGLUND!

Cuxhaven, Germany (53.8586, 8.7025) offers the best position for a bombing campaign against the British Isles, because it enables a near direct flight path to Britain over the North Sea, without having to violate Dutch or Belgian neutrality by overflying them.

This map aligns well with statements I have seen in various books that state that when WWII began in September 1939, German bombers (i.e. the most modern He-111 in service) could only reach London with 500 kilogram (1,100~ lb) bombloads.

It also makes it clear why the Luftwaffe wanted to wait for the Ju-88 to enter service in large numbers, and as a "dream", wanted to wait until 1942 and a force of four Kampfgeschwader of He-177 (about 400~) were in service at a minimum alongside about maybe ten Kampfgeschwader of Ju-88s (about 1,000~).

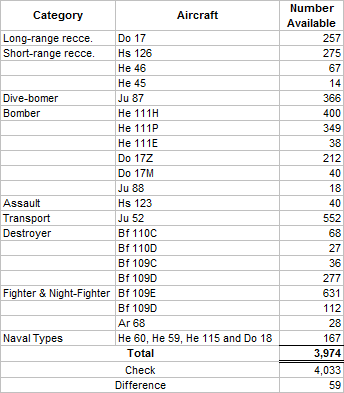

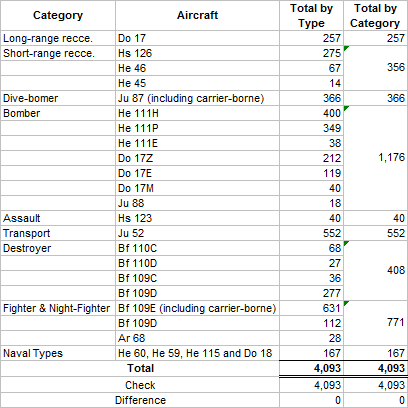

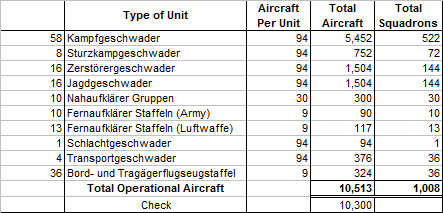

On 1 September 1939, the Luftwaffe's bomber force first line inventory was:

400 x He-111H

349 x He-111P

38 x He-111E

257 x Do-17E

212 x Do-17Z

40 x Do-17M

18 x Ju-88

Out of this, only the 749 x He-111s are capable of reaching England; and even then you might not be able to fit all of them into the Bremen-Cuxhaven area in Northern Germany due to airfield limitations. Plus, due to the increasing obsolescence of the Dornier 17 force (about half are older E models, versus the newer Z); you'll need to use your He-111s to backstop them.

So you've only got about maybe 300 x He-111s capable of striking England. Assume a 85% dispatch rate; and that's 255 planes going out every day; figure about 200~ or less actually hit the target.

At 500 kilos of bombs per plane, that's only 100 metric tons of high explosive you're dropping on either London or eastern England.

If you wait until you get 300 x Ju-88s in service, you can reach most of England with twice the bombload; or 200 metric tons per raid.

If you get really lucky and Hitler doesn't go crazy until 1942; you'll have a force of probably about 200 He-177 and 1,000 Ju-88s; letting you drop 1,198 metric tons in each raid; of which 532 metric tons will come from the He-177 "überbombers".

If we alter things to June 1940 and the fall of France with Montdidier, France (49.6486, 2.5708) as our airfield area we've got this strategic layout:

Suddenly, lots of things are in our favor.

Our shorter ranged Dorniers can actually reach targets of importance, effectively doubling our bomber force, and we can carry heavier payloads to targets like London.

References:

The German Air Force, 1933-1945: An Anatomy of Failure by Matthew Cooper

Battle of Britain 1940: The Luftwaffe’s ‘Eagle Attack’ by Douglas C. Dildy

Dornier Do 17 Units of World War 2 by Chris Goss

Ju 52/3m Bomber and Transport Units 1936-41 by Robert Forsyth

German Aircraft Industry and Production: 1933-1945 by Ferec Vajda and Peter Dancey

Heinkel He-177, 277, 274 by Manfred Griel and Joachim Dressel

The Army Air Forces in World War II, Volume Six: Men and Planes