You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

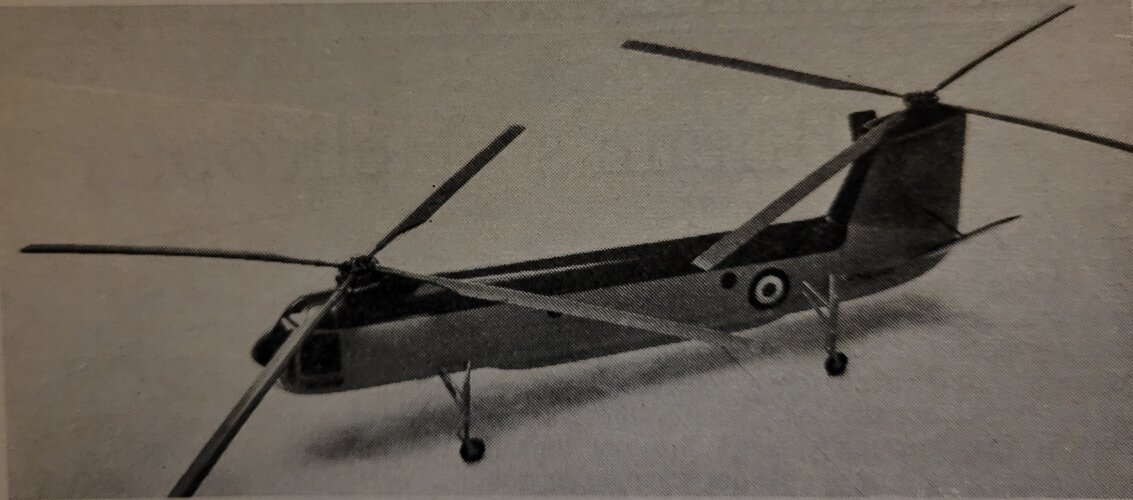

Bristol Type 191 Scenario

- Thread starter zen

- Start date

- Joined

- 6 September 2006

- Messages

- 4,340

- Reaction score

- 7,559

An interesting scenario, one close to my interests.

RCN: not sure. I haven't seen any details about how their Type 193 helicopters were to be operated, I assume they would have been carrier-based aboard Bonaventure. Of course the big rival is the S-2 Tracker which de Havilland Canada already had a licence-contract for in 1954. They entered service in 1957. I don't know if the decision to acquire Tracker was connected with the decision not to buy the Type 193, the 191 was not cancelled until 1955 so there is an overlap in the timeline. Its possible the Type 193s would have been shore-based instead.

Exports: France and Australia were interested. Australia though brought Gannets, France went with Alize. Both were around the time of the end of the Type 191 programme. The Dutch brought ex-USN Trackers in 1960 so they might have been a possible export nation. The battle between fixed and rotary wing is open to debate, arguably the Type 191 would have needed 2-3 years to prove itself and by then it would probably too late and the S-61 would be a powerful competitor.

Of course the Type 192 Belvedere had no export success so its hard to gauge.

FAA career: I would say that the Type 191 would have been retired in 1970-71 when the Sea King came on line, something smaller would be inevitable I think as helicopters developed in capability. The loss of the Wessex might have had a greater impact, although Westland might have been successful in pushing for the Commando Wessex variants for the Navy. It means the County-class destroyers would likely have had to wait for Wasp and MATCH (no bad thing).

Then there is the question of reliability. The Belvedere has a poor reputation, largely due to its heavy use in hot and high war zones and the type never really finished development with just a small batch built. Most of the problems were due to the Avpin starters causing fires, the Gazelles were temperamental too. I assume the RN would not have accepted the switch to Avpin and would have insisted on keeping the Rover Neptune APU. I think it would have performed ok but would have been restricted to the Hermes-class ships due to the desire to keep the fleet carriers free for jets.

RCN: not sure. I haven't seen any details about how their Type 193 helicopters were to be operated, I assume they would have been carrier-based aboard Bonaventure. Of course the big rival is the S-2 Tracker which de Havilland Canada already had a licence-contract for in 1954. They entered service in 1957. I don't know if the decision to acquire Tracker was connected with the decision not to buy the Type 193, the 191 was not cancelled until 1955 so there is an overlap in the timeline. Its possible the Type 193s would have been shore-based instead.

Exports: France and Australia were interested. Australia though brought Gannets, France went with Alize. Both were around the time of the end of the Type 191 programme. The Dutch brought ex-USN Trackers in 1960 so they might have been a possible export nation. The battle between fixed and rotary wing is open to debate, arguably the Type 191 would have needed 2-3 years to prove itself and by then it would probably too late and the S-61 would be a powerful competitor.

Of course the Type 192 Belvedere had no export success so its hard to gauge.

FAA career: I would say that the Type 191 would have been retired in 1970-71 when the Sea King came on line, something smaller would be inevitable I think as helicopters developed in capability. The loss of the Wessex might have had a greater impact, although Westland might have been successful in pushing for the Commando Wessex variants for the Navy. It means the County-class destroyers would likely have had to wait for Wasp and MATCH (no bad thing).

Then there is the question of reliability. The Belvedere has a poor reputation, largely due to its heavy use in hot and high war zones and the type never really finished development with just a small batch built. Most of the problems were due to the Avpin starters causing fires, the Gazelles were temperamental too. I assume the RN would not have accepted the switch to Avpin and would have insisted on keeping the Rover Neptune APU. I think it would have performed ok but would have been restricted to the Hermes-class ships due to the desire to keep the fleet carriers free for jets.

- Joined

- 11 March 2012

- Messages

- 3,016

- Reaction score

- 2,702

Could Bristol Type 191 fold into a Sea King-sized hangar?

The 1950s were a difficult time for the Royal Canadian Navy, while they struggled to define their Cold War mission. In 1950, the RCN wanted to retain competence in a variety of roles: fleet defence, ground attack, anti-submarine, etc. Successive budget cuts forced them to retire Banshee fighters and aircraft carriers. "Bonny" only carried Trackers and Sea Kings on her last few cruises. HMCS Bonaventure's career over-lapped with RCN development of the Beartrap helicopter haul down and traversing system, which was built around Sikorsky Sea King SH3 (aka. S-61 or CH-124) after Sikorsky's S-61 won out over Kaman Sea Sprite, etc. The RCN even posted a few helicopter pilots to USN Sea Sprite squadrons to gain experience.

By 1970, RCN had standardized on DDEs and DDHs carrying one or two Sea King helicopters.

I worked on the flight decks of HMCS Athabaskan and HMCS Iroquois during the 1980s.

The 1950s were a difficult time for the Royal Canadian Navy, while they struggled to define their Cold War mission. In 1950, the RCN wanted to retain competence in a variety of roles: fleet defence, ground attack, anti-submarine, etc. Successive budget cuts forced them to retire Banshee fighters and aircraft carriers. "Bonny" only carried Trackers and Sea Kings on her last few cruises. HMCS Bonaventure's career over-lapped with RCN development of the Beartrap helicopter haul down and traversing system, which was built around Sikorsky Sea King SH3 (aka. S-61 or CH-124) after Sikorsky's S-61 won out over Kaman Sea Sprite, etc. The RCN even posted a few helicopter pilots to USN Sea Sprite squadrons to gain experience.

By 1970, RCN had standardized on DDEs and DDHs carrying one or two Sea King helicopters.

I worked on the flight decks of HMCS Athabaskan and HMCS Iroquois during the 1980s.

Last edited:

- Joined

- 27 September 2006

- Messages

- 5,744

- Reaction score

- 5,648

The Australians,Canadians, and the Dutch all used the Tracker for the remaining lives of their carriers.

MDAP Trackers for the RN would have been an interesting alternative to the Gannet. But between 1957 and 1962 the UK believed the war would go thermonuclear quickly and got out of developing shipboard ASW. See the NATO document posted by JFCFuller for the threadbare state of UK ASW in 1959.

When we do get interested, as Hood can explain, we look at the big CH47.

MDAP Trackers for the RN would have been an interesting alternative to the Gannet. But between 1957 and 1962 the UK believed the war would go thermonuclear quickly and got out of developing shipboard ASW. See the NATO document posted by JFCFuller for the threadbare state of UK ASW in 1959.

When we do get interested, as Hood can explain, we look at the big CH47.

- Joined

- 6 September 2006

- Messages

- 4,340

- Reaction score

- 7,559

Could Bristol Type 191 fold into a Sea King-sized hangar?

The fuselage was 50ft 3in (15.3m) long, a folded Sea King was 47ft 3in (14.4m), not sure on the folded width but the aim was have the blades folded within the footprint of the fuselage diameter, so the difference between the two types would not be great. But you would need a large flight deck for safe operations, those tandem rotors eating up a lot of space when unfolded.

- Joined

- 22 April 2012

- Messages

- 2,321

- Reaction score

- 1,857

An ideal CVS air wing would, just as those of the USN did, have both fixed wing aircraft for sonobuoy searches and dipping sonar equipped helicopters for target localisation and prosecution. That is to say that the two capabilities were complimentary.

The issue with the Type 191, as Hood has eloquently demonstrated, was that it was never going to be able to operate from anything other than a carrier due to the tandem rotors and long, non folding, fuselage and resultant undercarriage arrangement. Overall the RN appears to have missed a trick, the ideal solution was a medium-large single rotor type of approximately Wessex (or Type 214/WG.4/WG7) size deployed across the escort fleet. That is what Mountbatten pushed for with the County class. However, when consideration was given to a slightly larger frigate with the ability to carry a Wessex for the 1959/60 frigates (FSA.21-23) the idea went nowhere so the entire frigate force ended up using the Wasp and then the Lynx as, in ASW terms, little more than a torpedo delivery system until it was decided in the late 1970s that Type 22s from HMS Brave onwards should be able to operate a big helicopter. By contrast, the Royal Canadian Navy had figured out by 1959 that big helicopters on frigates and destroyers was the way forwards and developed the Bear Trap to facilitate it.

The issue with the Type 191, as Hood has eloquently demonstrated, was that it was never going to be able to operate from anything other than a carrier due to the tandem rotors and long, non folding, fuselage and resultant undercarriage arrangement. Overall the RN appears to have missed a trick, the ideal solution was a medium-large single rotor type of approximately Wessex (or Type 214/WG.4/WG7) size deployed across the escort fleet. That is what Mountbatten pushed for with the County class. However, when consideration was given to a slightly larger frigate with the ability to carry a Wessex for the 1959/60 frigates (FSA.21-23) the idea went nowhere so the entire frigate force ended up using the Wasp and then the Lynx as, in ASW terms, little more than a torpedo delivery system until it was decided in the late 1970s that Type 22s from HMS Brave onwards should be able to operate a big helicopter. By contrast, the Royal Canadian Navy had figured out by 1959 that big helicopters on frigates and destroyers was the way forwards and developed the Bear Trap to facilitate it.

Last edited:

- Joined

- 27 September 2006

- Messages

- 5,744

- Reaction score

- 5,648

Some illustrations to go with the thread.

blurred images from Shipbucket..Sorry Hood.

An RAF Belvedere on HMS Centaur (my ASW carrier)

QE with a flight of Chinooks. They could still carry a pretty decent ASW load and are likely to be in production longer after EH101.

blurred images from Shipbucket..Sorry Hood.

An RAF Belvedere on HMS Centaur (my ASW carrier)

QE with a flight of Chinooks. They could still carry a pretty decent ASW load and are likely to be in production longer after EH101.

Attachments

It lifts the full ASW suite, whereas the Wessex didn't.

It hovers over an area, whereas a Tracker cannot.

It was on order for the RN.

While the Whirlwind HAS.7 could lift either the dipping sonar OR the homing torpedo / depth charge, AIUI the Wessex HAS.1 could do both at the same time in the one airframe. So what is missing from the Wessex ASW suite that was in the Type 191 suite?

No that's me not able to check if my memory is coming up with the right names.It lifts the full ASW suite, whereas the Wessex didn't.

It hovers over an area, whereas a Tracker cannot.

It was on order for the RN.

While the Whirlwind HAS.7 could lift either the dipping sonar OR the homing torpedo / depth charge, AIUI the Wessex HAS.1 could do both at the same time in the one airframe. So what is missing from the Wessex ASW suite that was in the Type 191 suite?

Isn't wonderful when you have no interruptions.....

Last edited:

GT6Boy

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 3 November 2017

- Messages

- 53

- Reaction score

- 173

Just had a marvellous discussion on Fb and I queried which of the Commando Carriers this Belvedere is enjoying a trip on. A fella on board confirmed it was HMS Albion in October 1963Some illustrations to go with the thread.

blurred images from Shipbucket..Sorry Hood.

An RAF Belvedere on HMS Centaur (my ASW carrier)

QE with a flight of Chinooks. They could still carry a pretty decent ASW load and are likely to be in production longer after EH101.

Attachments

GT6Boy

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 3 November 2017

- Messages

- 53

- Reaction score

- 173

I thought the 191 was designed to meet critical transit from ship to operating area requirements, these were pretty stretching. I understood the Wessex HAS.3 could carry out Hunter Killer role, but not over said distance?No that's me not able to check if my memory is coming up with the right names.It lifts the full ASW suite, whereas the Wessex didn't.

It hovers over an area, whereas a Tracker cannot.

It was on order for the RN.

While the Whirlwind HAS.7 could lift either the dipping sonar OR the homing torpedo / depth charge, AIUI the Wessex HAS.1 could do both at the same time in the one airframe. So what is missing from the Wessex ASW suite that was in the Type 191 suite?

Isn't wonderful when you have no interruptions.....

GT6Boy

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 3 November 2017

- Messages

- 53

- Reaction score

- 173

As an aside, the fella also confirmed they did indeed manage to get all 26 Whirlwind AND the 3 Belvedere into the hanger!Just had a marvellous discussion on Fb and I queried which of the Commando Carriers this Belvedere is enjoying a trip on. A fella on board confirmed it was HMS Albion in October 1963Some illustrations to go with the thread.

blurred images from Shipbucket..Sorry Hood.

An RAF Belvedere on HMS Centaur (my ASW carrier)

QE with a flight of Chinooks. They could still carry a pretty decent ASW load and are likely to be in production longer after EH101.

- Joined

- 6 September 2006

- Messages

- 4,340

- Reaction score

- 7,559

I thought the 191 was designed to meet critical transit from ship to operating area requirements, these were pretty stretching. I understood the Wessex HAS.3 could carry out Hunter Killer role, but not over said distance?

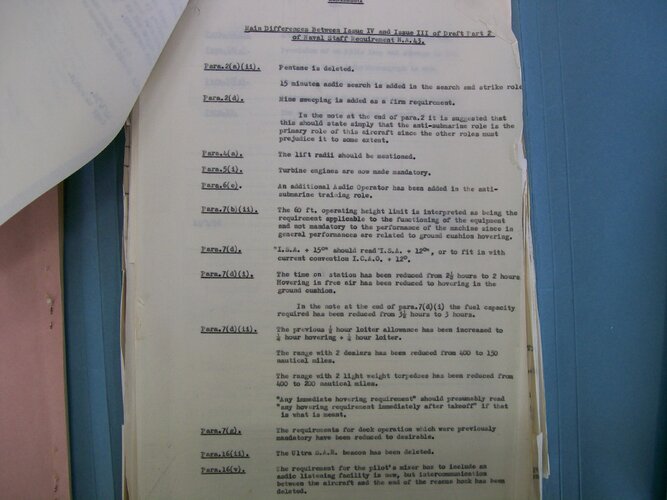

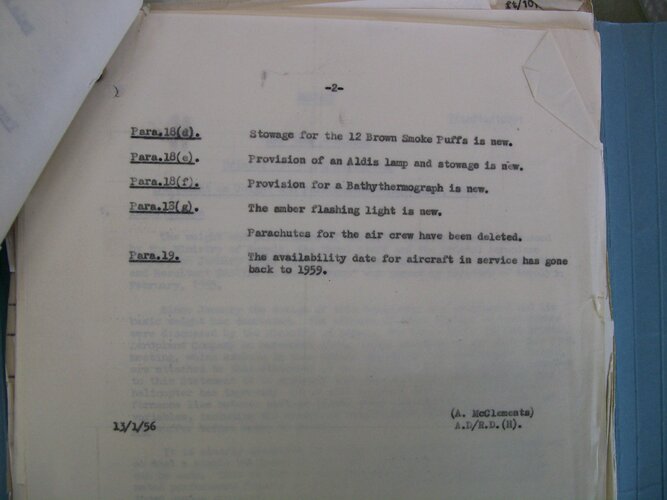

Yes, NA.43 Issue 4 was reduced to enable the Wessex to meet it. Sonar search endurance was increased by 15 minutes but time on station was reduced to two hours and max endurance fell from four to three hours. Range with two torpedoes fell from 400nm to 150nm.

Arguably NA.43 had been a bit too ambitious given the technology of the time.

GT6Boy

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 3 November 2017

- Messages

- 53

- Reaction score

- 173

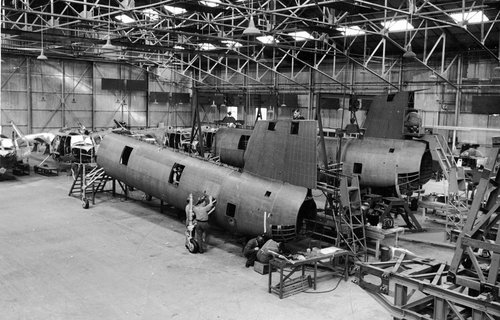

I've had these scanned now. My late fathers images, accrued by him whilst working in the HDO (Helicopter Design office) at Bristol Aeroplane Company Helicopter Division/then Westland 1953 to 1987.

The first is 2 of the 3 191 airframes being built originally with provision for the Alvis Leonides Major engine. This may be at Filton, or possibly Oldmixon. The 2nd image shows the Ground Rig 1 aircraft on the Test gantry at Oldmixon, when converted for use as a test airframe for the Napier Gazelle engine, icw the Type 192/Belvedere.

The first is 2 of the 3 191 airframes being built originally with provision for the Alvis Leonides Major engine. This may be at Filton, or possibly Oldmixon. The 2nd image shows the Ground Rig 1 aircraft on the Test gantry at Oldmixon, when converted for use as a test airframe for the Napier Gazelle engine, icw the Type 192/Belvedere.

Attachments

GT6Boy

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 3 November 2017

- Messages

- 53

- Reaction score

- 173

Can I ask a questions please:Most of the problems were due to the Avpin starters causing fires, the Gazelles were temperamental too. I assume the RN would not have accepted the switch to Avpin and would have insisted on keeping the Rover Neptune APU. I think it would have performed ok but would have been restricted to the Hermes-class ships due to the desire to keep the fleet carriers free for jets.

Who stipulated the Avpin system for the series 2 191 for the Admiralty and consequently the Air Staff's 192 - MoS or Admiralty?

GT6Boy

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 3 November 2017

- Messages

- 53

- Reaction score

- 173

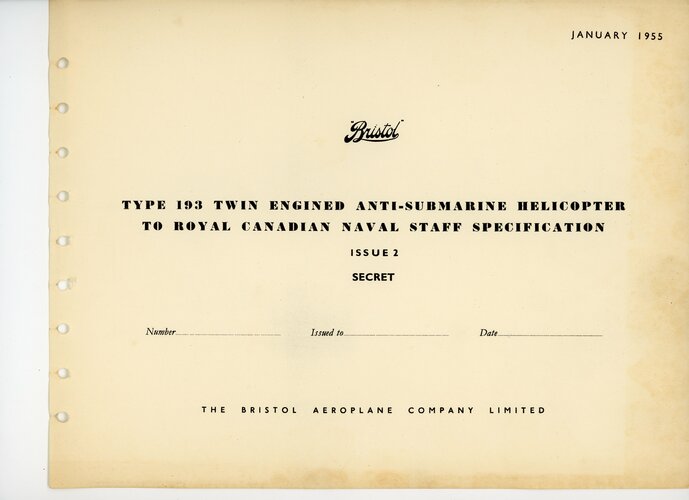

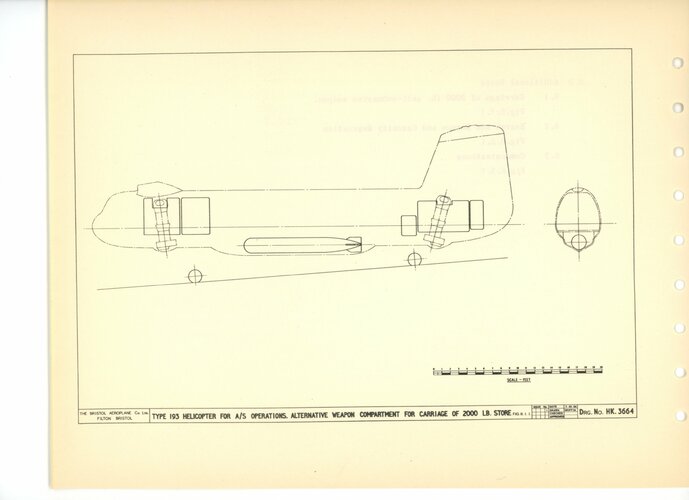

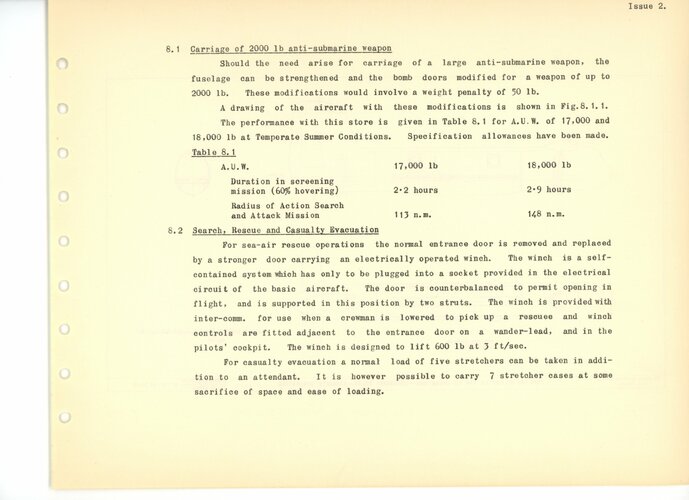

Just thought I'd add this revealing page from Issue 2 of the Type 193 to RCN Naval Staff Specification- was the 2000lb Store- or large anti-submarine weapon otherwise known as a nuclear device?

Attachments

- Joined

- 11 March 2012

- Messages

- 3,016

- Reaction score

- 2,702

RCN never publically admitted to having any nuclear ordinance. A lower deck rumor suggested that nuclear depth charges were stored at Bedford bomb dump. I have never seen anything in print to confirm this rumor.Just thought I'd add this revealing page from Issue 2 of the Type 193 to RCN Naval Staff Specification- was the 2000lb Store- or large anti-submarine weapon otherwise known as a nuclear device?

GT6Boy

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 3 November 2017

- Messages

- 53

- Reaction score

- 173

Thanks Rob. Perhaps it’s the slightly less intriguing then secret Pentane 21” torpedo?RCN never publically admitted to having any nuclear ordinance. A lower deck rumor suggested that nuclear depth charges were stored at Bedford bomb dump. I have never seen anything in print to confirm this rumor.

Scott Kenny

ACCESS: Above Top Secret

- Joined

- 15 May 2023

- Messages

- 6,253

- Reaction score

- 5,100

Most of the first generation nuclear depth charges were in the 1500lb weight class. The US Mk90 and Mk101 bombs were ~1200lbs, while the Mk105 was a 1700lb weapon due to the hardened steel nose for earth penetration. Those were phased out in the mid 1960s.Just thought I'd add this revealing page from Issue 2 of the Type 193 to RCN Naval Staff Specification- was the 2000lb Store- or large anti-submarine weapon otherwise known as a nuclear device?

Second generation NDBs were in the 600lb weight class. WE177A was 600lbs, and the US B57 weighed in at 500lbs.

So I'm leaning towards a 21" homing torpedo. The US Mk13 air-dropped torpedo of WW2 was 2200lbs in its final form, and the later Mk34 homing torpedo was down to 1200lbs.

GT6Boy

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 3 November 2017

- Messages

- 53

- Reaction score

- 173

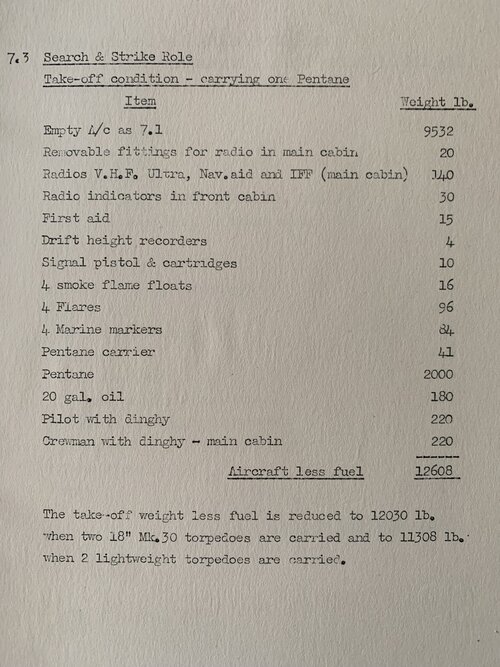

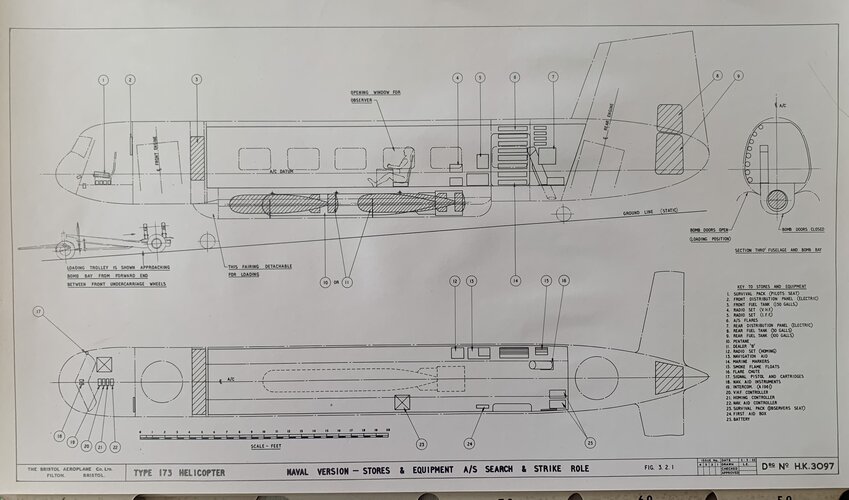

Looking at the earlier March 1953 equivalent brochure for the then Type 173 mk3 to NA43, this details the 2000lb weapon as Pentane. I presume the Type 193 being for the RCN, the then secret nature of Pentane precluded it being detailed for a foreign potential buyer?

Attachments

GT6Boy

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 3 November 2017

- Messages

- 53

- Reaction score

- 173

Thanks- I’m loving researching the 173/191/193. It was such a complex time: the MoS were trying to get the UK aviation into the marketplace after the hiatus in UK design effort of WW2, meanwhile the armed forces and BEA were all rather hoping the other would pay for any development!Back with the figure - Pentane was 1,950lb. Rounded to 2,000lb this makes perfect sense.

- Joined

- 20 January 2007

- Messages

- 897

- Reaction score

- 923

Spraying Mantis, a military hauler, was funded on the Colonial Devt. budget.

Who cares to speculate on why Piaseki went from odd Bananas to Centurion standard, while the cut-and-shut way of turning 2xSycamore into 1xT173/19X was an inflammatory disaster. Owners of Bristol Aeroplane could call in 1950s on more resources, yet failed.

Who cares to speculate on why Piaseki went from odd Bananas to Centurion standard, while the cut-and-shut way of turning 2xSycamore into 1xT173/19X was an inflammatory disaster. Owners of Bristol Aeroplane could call in 1950s on more resources, yet failed.

- Joined

- 6 September 2006

- Messages

- 4,340

- Reaction score

- 7,559

Who cares to speculate on why Piaseki went from odd Bananas to Centurion standard, while the cut-and-shut way of turning 2xSycamore into 1xT173/19X was an inflammatory disaster. Owners of Bristol Aeroplane could call in 1950s on more resources, yet failed.

I can try. The elements are probably multi-facteted as always.

1. Flying - Raoul Hafner knew what he was doing. The 171 and 173 series were good handling helicopters, Hafner's rotor hub designs were good - they handled better in manual control than most US designs. The switch from wooden to metal rotor blades probably took longer than it should have.

2. Engine - the lack of decent British engines with good power/weight ratios didn't help. Leonides Major proved an expensive flop not suited to the helicopter role, but only after a lot of work had been expended. Luckily gas turbines appeared on the scene but probably at the wrong time for the design overall (see below).

The Avpin starter was a big mistake. The MoS applying too much fixed-wing thinking - they should have realised helicopters stop and start their engines more often than a normal aircraft. The Trials Unit were too scared of cancellation if they raised an expensive and time-consuming change to pressurised air starting and of course the lack of prototypes made the change unwelcome.

3. Layout - when the 173 was designed it was reasonable to simply bolt two Sycamore engine/transmission packages either side of the cabin. A lot of pioneering designs used this layout and for civil use this didn't seem a problem. It wasn't a handicap to naval operations and the RAF probably hadn't really thought out the logistical issues of what it might carry in the SH variant (they were still messing about with tailwheel Hastings for example!). Not keeping the original 173 castoring wheel set-up was another mistake, retaining the naval undercarriage designed for easy access for torpedo loading was silly given the transport role needed a low sill high for the door.

Arguably when the gas turbine came about the ideal would have been to take stock and redesign the airframe for more efficient packaging of the Gazelles - perhaps with a rear ramp and engines on top. Alas time and money wasn't there and with 191s and 192s already on the production line such a change was impossible so the engine layout had to remain.

4. Policy - a big stumbling block was procurement policy. The RN knew what it wanted but didn't realise what it wanted was impossible (the single-package with dipping sonar and a 21in 2,000lb weapon - effectively a hovering Barracuda!). The result was always going to be too heavy (it took them until 1965 before they cottoned on to that). The RAF didn't know what it wanted except that it didn't want the Army flying whatever it wanted. The SH force was small and underfunded, helicopters could do everything but that made pinning down specifications harder and a force of 15-20 helicopters was far too small for any UK helicopter programme to be remotely profitable. Eventually 192 was seen as a heavy lifter - which it was compared to standards of the Whirlwind - but really it was a medium lugger. But there were never funds for more than a couple of squadrons worth and so prototypes were dispensed with in favour of believing the original 173 prototypes were sufficient and building off the drawing board. That was a mistake. The MoS devised an R&D programme on the cheap and it showed. It led to bigger mistakes like the starter and undercarriage.

5. NASR.358 - the Westland W.11 of 1963 was born out of the 193-194 series of stillborn projects and had a lot of Bristol DNA. This Vertol V.107 CH-46A lookalike was something approaching CH-47A performance. But the RN could never use it effectively aboard ships and the RAF could never afford to fund it alone for the sake of 15 helicopters. So Bristol never had a chance - the naval need was there with enough numbers for good production but was technically a dead-end, the air force/army need lacked enough numbers but was technically achievable.

GT6Boy

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 3 November 2017

- Messages

- 53

- Reaction score

- 173

Having previously spoken with the late Reg Austin (a senior member Raoul Hafner's Helicopter Design Office), he was very clear he felt the Bristol Aeroplane Company in its entirety, didn't fully support the Helicopter Division.Spraying Mantis, a military hauler, was funded on the Colonial Devt. budget.

Who cares to speculate on why Piaseki went from odd Bananas to Centurion standard, while the cut-and-shut way of turning 2xSycamore into 1xT173/19X was an inflammatory disaster. Owners of Bristol Aeroplane could call in 1950s on more resources, yet failed.

That in itself is perhaps not unlike the post-war position of the senior echelons of the armed forces, who were largely devoid of rotary wing experience- at least until the urgent demands of the Malayan theatre saw the helicopter value increase exponentially.

Not withstanding their moving of almost the entire Helicopter design and manufacture to the Oldmixon site in 1955, the earlier lack of BAC's progression of their interest in the Bristol Janus helicopter specific gas turbine, meant the 173 was hamstrung from the outset with the reciprocating Leonides. Perhaps that was emblematic of the BAC outlook toward their Helicopter function?

The arrival of the indigenous Napier Gazelle helicopter gas turbine, at a stroke imbued the helicopter with a new functionality.

Whilst the public proclamations of Raoul Hafner and Bristol regarding the 173 flying characteristics can be looked at now with some degree of optimism (A&AEE reports were strongly unfavourable- be that the 3 rotor or 4 rotor blade iteration); to call the 173 cut'n'shut or Bristol's twin rotor work an inflammatory disaster is (I feel) unnecessarily condemnatory in-tone and underplays their technical achievements and the great lengths those involved went to, in an effort to develop this nascent technology.

Reg Austin was very keen to fair-handedly point out the support Westland directed toward all things twin-rotor, after their taking on the Bristol HDO team.

Jack Hobbs autobiography was published in 1984, in tribute to Raoul Hafner. It makes for an interesting read- although it suffers a little in his recollections being conflated, on occasion.

An objective look at Raoul Hafner's work would make for an excellent book in itself.

GT6Boy

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 3 November 2017

- Messages

- 53

- Reaction score

- 173

I think that's an objective and fair summary- you should write(another) book on the subject!I can try. The elements are probably multi-facteted as always.

1. Flying - Raoul Hafner knew what he was doing. The 171 and 173 series were good handling helicopters, Hafner's rotor hub designs were good - they handled better in manual control than most US designs. The switch from wooden to metal rotor blades probably took longer than it should have.

2. Engine - the lack of decent British engines with good power/weight ratios didn't help. Leonides Major proved an expensive flop not suited to the helicopter role, but only after a lot of work had been expended. Luckily gas turbines appeared on the scene but probably at the wrong time for the design overall (see below).

The Avpin starter was a big mistake. The MoS applying too much fixed-wing thinking - they should have realised helicopters stop and start their engines more often than a normal aircraft. The Trials Unit were too scared of cancellation if they raised an expensive and time-consuming change to pressurised air starting and of course the lack of prototypes made the change unwelcome.

3. Layout - when the 173 was designed it was reasonable to simply bolt two Sycamore engine/transmission packages either side of the cabin. A lot of pioneering designs used this layout and for civil use this didn't seem a problem. It wasn't a handicap to naval operations and the RAF probably hadn't really thought out the logistical issues of what it might carry in the SH variant (they were still messing about with tailwheel Hastings for example!). Not keeping the original 173 castoring wheel set-up was another mistake, retaining the naval undercarriage designed for easy access for torpedo loading was silly given the transport role needed a low sill high for the door.

Arguably when the gas turbine came about the ideal would have been to take stock and redesign the airframe for more efficient packaging of the Gazelles - perhaps with a rear ramp and engines on top. Alas time and money wasn't there and with 191s and 192s already on the production line such a change was impossible so the engine layout had to remain.

4. Policy - a big stumbling block was procurement policy. The RN knew what it wanted but didn't realise what it wanted was impossible (the single-package with dipping sonar and a 21in 2,000lb weapon - effectively a hovering Barracuda!). The result was always going to be too heavy (it took them until 1965 before they cottoned on to that). The RAF didn't know what it wanted except that it didn't want the Army flying whatever it wanted. The SH force was small and underfunded, helicopters could do everything but that made pinning down specifications harder and a force of 15-20 helicopters was far too small for any UK helicopter programme to be remotely profitable. Eventually 192 was seen as a heavy lifter - which it was compared to standards of the Whirlwind - but really it was a medium lugger. But there were never funds for more than a couple of squadrons worth and so prototypes were dispensed with in favour of believing the original 173 prototypes were sufficient and building off the drawing board. That was a mistake. The MoS devised an R&D programme on the cheap and it showed. It led to bigger mistakes like the starter and undercarriage.

5. NASR.358 - the Westland W.11 of 1963 was born out of the 193-194 series of stillborn projects and had a lot of Bristol DNA. This Vertol V.107 CH-46A lookalike was something approaching CH-47A performance. But the RN could never use it effectively aboard ships and the RAF could never afford to fund it alone for the sake of 15 helicopters. So Bristol never had a chance - the naval need was there with enough numbers for good production but was technically a dead-end, the air force/army need lacked enough numbers but was technically achievable.

British helicopter development is a very interesting subject but- finding a publisher willing to engage with a suitably accurate(for that read large) tome, is akin to the struggles of the British Helicopter industry itself; never enough likely orders to make it wholly viable.

- Joined

- 20 January 2007

- Messages

- 897

- Reaction score

- 923

Hood: Thank you. GT6: my tone is journalistic, but 2xSycamore dynamics did become 1xT.173 and many Belvederes burnt: “injuries (were) limited (to) sprains incurred by crews vacating (in ) rather a hurry (not) waiting for the ladder.” R.G.Bedford,RAF Rotors,SFB,96,P96.

Hood's Admiralty &Heli,P.10: "Fairey had an agreement to buy a (HUP Retriever) license if a Br buyer was found" (context: 1953/54: (to be) Whirlwind HAS.7 won, flying 17/10/56). Pp.27/28: WG.1, "devt start 10/62" "clean-sheet", "very similar to CH-46A". You are too polite.

Piaseki and Fairey,1956 did a 2-way licence option: Ultra-Light OUT, H-21 IN. Frank Piaseki was then ousted, His firm started on CH-46, 1957 on CH-47, renamed, bought by Boeing, 1960 when Fairey was bought by Westland, who: "has entered into a licensing Ag with Boeing-Vertol (for) V-107" US Dept of Commerce 3/65 https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/World_Survey_of_ Civil_Aviation P.5.

Hood's P.28 has WG.1 design input from Bristol and Fairey, but P.29,'65: "MoA doubted Westland's ability to develop and produce WG.1".

I suggest the (ex-Piaseki) licence option was an asset in valuing Fairey into Westland (they had little else, GW/Jindivik and PFCUs excluded) and I suggest WG.1/WG.11 were not look-alike, but "Anglicised". I also suggest MoA had no idea in 1965 what to do about its rotory monopoly, which by then had lost its Bristol/Fairey/Saro design teams: RAF was already flirting for CH-47B, RN for SH-3D...off-the-shelf.

All of this caused 5/65 Anglo-French Jaguar/AFVG package to intend rotors...but not yet. (Anglicised SH-3D funded 9/66, MOTS CH-47B, 3/67 (canx 11/67), the Gazelle/Puma/WG.13 package, 2/67).

Piaseki (and Sikorsky) survived departure of their genius founders; Hafner, Dr.Bennett were replaced in new-Westland by no genius.

You stress, above, lack of good UK engines (until Nimbus and Gnome, both Anglicised licensed). There is a missing ingredient here to explain why 1957 CH-47 will serve for a century, while '52-origin Belvedere is a how-not-to-do-it exemplar, those unburnt dumped 1969.

Hood's Admiralty &Heli,P.10: "Fairey had an agreement to buy a (HUP Retriever) license if a Br buyer was found" (context: 1953/54: (to be) Whirlwind HAS.7 won, flying 17/10/56). Pp.27/28: WG.1, "devt start 10/62" "clean-sheet", "very similar to CH-46A". You are too polite.

Piaseki and Fairey,1956 did a 2-way licence option: Ultra-Light OUT, H-21 IN. Frank Piaseki was then ousted, His firm started on CH-46, 1957 on CH-47, renamed, bought by Boeing, 1960 when Fairey was bought by Westland, who: "has entered into a licensing Ag with Boeing-Vertol (for) V-107" US Dept of Commerce 3/65 https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/World_Survey_of_ Civil_Aviation P.5.

Hood's P.28 has WG.1 design input from Bristol and Fairey, but P.29,'65: "MoA doubted Westland's ability to develop and produce WG.1".

I suggest the (ex-Piaseki) licence option was an asset in valuing Fairey into Westland (they had little else, GW/Jindivik and PFCUs excluded) and I suggest WG.1/WG.11 were not look-alike, but "Anglicised". I also suggest MoA had no idea in 1965 what to do about its rotory monopoly, which by then had lost its Bristol/Fairey/Saro design teams: RAF was already flirting for CH-47B, RN for SH-3D...off-the-shelf.

All of this caused 5/65 Anglo-French Jaguar/AFVG package to intend rotors...but not yet. (Anglicised SH-3D funded 9/66, MOTS CH-47B, 3/67 (canx 11/67), the Gazelle/Puma/WG.13 package, 2/67).

Piaseki (and Sikorsky) survived departure of their genius founders; Hafner, Dr.Bennett were replaced in new-Westland by no genius.

You stress, above, lack of good UK engines (until Nimbus and Gnome, both Anglicised licensed). There is a missing ingredient here to explain why 1957 CH-47 will serve for a century, while '52-origin Belvedere is a how-not-to-do-it exemplar, those unburnt dumped 1969.

Last edited:

- Joined

- 6 September 2006

- Messages

- 4,340

- Reaction score

- 7,559

Sadly the publishers still feel that the rotary niche on the bookhself is too small, though increasing numbers of rotary winged books are trickling out in recent years.I think that's an objective and fair summary- you should write(another) book on the subject!

British helicopter development is a very interesting subject but- finding a publisher willing to engage with a suitably accurate(for that read large) tome, is akin to the struggles of the British Helicopter industry itself; never enough likely orders to make it wholly viable.

Yes they did. It seems odd (or perhaps more accurately ironic) that having created a centralised "brains trust" of helicopter design and manufacture just two years before that it could not be trusted to actually deliver a helicopter. None of the WG.1 to 12 designs were appealing at all in any role and some of them look quite amateurish compared with US or even French designs of the early 1960s. As you say, the 'brains' of Hafner and Bennett were lost and Westland was too reliant on tracing over Sikorsky tracks - though WG.13 showed what could be achieved. Lynx is probably the only UK helicopter design that was actually successful off its own bat (though WG.30 flopped badly).Hood's P.28 has WG.1 design input from Bristol and Fairey, but P.29,'65: "MoA doubted Westland's ability to develop and produce WG.1".

WG.1 I think was doable but it wouldn't have been cheap and there just wasn't enough military market to justify it. And with it it's possible WG.13 might never have come about due to lack of resources at the start of the programme.

Fairey was probably shrewd in offering the H-21, especially as Westland was licencing the H-37 at that time. Fairey was even smart enough to recognise that it needed Mamba turboshafts. But in itself, as an interim to the 191 it made no sense given the level of work required and in theory a Mamba-powered H-21 could probably have done the same job as the 191 and 192 rendering them surplus to requirements (the stock H-21 would have been useless East of Suez as the US Army found in Vietnam in 1962).I suggest the (ex-Piaseki) licence option was an asset in valuing Fairey into Westland (they had little else, GW/Jindivik and PFCUs excluded)

Everything helicopter policy wise in 1949-56 is muddled, so many competing interests and overlapping deals and little to show for it.

Well the WG.1 started off reusing the Type 193 designation so in theory it was a continuation of the lineage although the 193 and 194 designs are a bit confusing with several versions of both floating around. There is some visual link of characteristics from the 194 into the WG.1. I think "convergent design" is probably more accurate (though of course British industry was involved in the Gnome Chinook so some furtive cross-fertlization was perhaps possible).I suggest WG.1/WG.11 were not look-alike, but "Anglicised"

Everyone wanted shot of it ASAP. Most of that was due to the terrible serviceability in Aden - but Aden was rough country that could grind down any machinery! There were far fewer problems in UK and Malaya where servicing facilities were better. But the poor reputation stuck. Plus with a tiny fleet on a shoestring spares situation was never good. 193 had no love from the start.There is a missing ingredient here to explain why 1957 CH-47 will serve for a century, while '52-origin Belvedere is a how-not-to-do-it exemplar, those unburnt dumped 1969.

Plus - learning from Malaya and Aden was learning on the hoof. Good for recognising what worked and what didn't in terms of equipment, flight operations and tactics but poor for actually feeding that from the frontline to the designers. In fact by the time of Aden UK helicopter design was all but dead (apart from Lynx) and any opportunity was lost. And we can't ignore that the first Chinook order was cancelled - heavy lift helicopters were low on the priority list and indicates how slim the chances were of every securing a home-grown design.

- Joined

- 20 January 2007

- Messages

- 897

- Reaction score

- 923

Talking of torque.

My "missing ingredient" to address Piaseki v. Bristol, might be simply fairy dust, the X Factor: hard work helped - ongoing Product Devt (funded by US DoD) despite ownership changes at Vertol and Lycoming. RR had no interest in Gazelle, nor, evidently Westland in Weston (both were bought at Ministers' request to assist industry coalescence: a cynic might suggest: to dump the ordure of closure).

For Heavy Lift, '60/61, Westland found themselves owning S.56/Westminster, Rotodyne, Belvedere, V-107 licence, S-61 licence, while Gazelle, then Gnome S-58s were doing well at Medium lift and could partly crossover. For the actual outcome, of MOTS RAF Chinooks, WS-61 Sea Kings for many and long, all while Lynx emerged, Directors would have blessed their Lucky Star.

Double dump.

If P1 survived sitting on a bomb at start up, he might then encounter this attrition factor: blowback in the long link between engines. Blamed by Napier on Bristol, by...you get the picture.

My "missing ingredient" to address Piaseki v. Bristol, might be simply fairy dust, the X Factor: hard work helped - ongoing Product Devt (funded by US DoD) despite ownership changes at Vertol and Lycoming. RR had no interest in Gazelle, nor, evidently Westland in Weston (both were bought at Ministers' request to assist industry coalescence: a cynic might suggest: to dump the ordure of closure).

For Heavy Lift, '60/61, Westland found themselves owning S.56/Westminster, Rotodyne, Belvedere, V-107 licence, S-61 licence, while Gazelle, then Gnome S-58s were doing well at Medium lift and could partly crossover. For the actual outcome, of MOTS RAF Chinooks, WS-61 Sea Kings for many and long, all while Lynx emerged, Directors would have blessed their Lucky Star.

Double dump.

If P1 survived sitting on a bomb at start up, he might then encounter this attrition factor: blowback in the long link between engines. Blamed by Napier on Bristol, by...you get the picture.

- Joined

- 6 September 2006

- Messages

- 4,340

- Reaction score

- 7,559

Agreed, in a world where the RN brought 110 191s, the RAF 60+ Belvederes, the Canadians 20-30 193s and BEA a few dozen 173s or 192Cs or 194s (plus maybe other airlines like SABENA) then the whole picture is changed and you've got a buzzing production line and lots of incentive to keep tinkering.

A (real) world of 26 Belvederes by contrast is a niche product.

Further to my cabin layout point in post #28, the cabin was probably too small for civil use too - headroom was a premium and it really needed a deeper fuselage I think.

A (real) world of 26 Belvederes by contrast is a niche product.

Further to my cabin layout point in post #28, the cabin was probably too small for civil use too - headroom was a premium and it really needed a deeper fuselage I think.

Scott Kenny

ACCESS: Above Top Secret

- Joined

- 15 May 2023

- Messages

- 6,253

- Reaction score

- 5,100

I'd argue that any civil helicopter where you can't just hop out the doors needs a passenger cabin tall enough to stand upright in. If only to make getting in and out minimally-unpleasant-enough that people will fly more than once!Agreed, in a world where the RN brought 110 191s, the RAF 60+ Belvederes, the Canadians 20-30 193s and BEA a few dozen 173s or 192Cs or 194s (plus maybe other airlines like SABENA) then the whole picture is changed and you've got a buzzing production line and lots of incentive to keep tinkering.

A (real) world of 26 Belvederes by contrast is a niche product.

Further to my cabin layout point in post #28, the cabin was probably too small for civil use too - headroom was a premium and it really needed a deeper fuselage I think.

- Joined

- 6 September 2006

- Messages

- 4,340

- Reaction score

- 7,559

Thanks to a tip from @TsrJoe I pulled a file at Kew on the Piasecki H-21 last week.My "missing ingredient" to address Piaseki v. Bristol, might be simply fairy dust, the X Factor: hard work helped - ongoing Product Devt (funded by US DoD) despite ownership changes at Vertol and Lycoming. RR had no interest in Gazelle, nor, evidently Westland in Weston (both were bought at Ministers' request to assist industry coalescence: a cynic might suggest: to dump the ordure of closure).

The basic outline seems to be: NA.43 had been raised for a tandem-rotor 'single package' ASW helicopter (i.e. one capable of both search and strike with sufficient payload to carry a sonar and a torpedo). An interim order was placed under MDAP funds for Bell HSLs but these never materialised as that helicopter was a flop and cancelled by the USN.

In January 1952 Sir Richard Fairey had travelled to meet Frank Piasecki to discuss a licence for the H-21, talks continuing to June 1953. Fairey pitched the H-21B or C for NA.43 but that was of no interest to the MoA/RN. Therefore Piasecki, via-Fairey, submitted a brochure for the H-21 powered by a single Armstrong Siddeley Mamba 6. Fairey would have been responsible for fitting the US-built fuselages of the first two prototypes with the Mamba and mission systems. Local manufacture would have come later.

Sir Richard Fairey argued that H.21 would not distract his firm from Rotodyne - something the MoA doubted given the resources Westland had to put into Anglicising Sikorsky designs - and would dovetail into the decline of Gannet production. The MoA instead hoped a Fairey-Bristol partnership might be more fruitful. Mr Jones as PDSR(A) went as far to say;

The big stumbling block was that the MoA hated the Mamba as it lacked sufficient power and would offer marginal safety on take-off, it was not a free-turbine and there might be dangerous instability combining the fixed-wheel turbine to the rotor drive (at that time the only successful gas-powered helicopter flown was the Kaman K.225 with the 175hp Boeing YT-50 free-turbine). So the offer was declined.I feel most strongly that we can't afford to keep four helicopter design teams in industry and at the same time buy helicopter designs from the U.S. Our design teams are, I am sure, as good as those in the U.S. and all they need is a production order or two to boost up their moral. [Sic]

And at this time Bristol was looking at fitting a developed Bristol Oryx free turbine into the 173 - that would eventually lead to the Gazelle-powered 191 and 192 Series 2.

The lack of suitable British engines again was the problem.

Against that, we should remember that at this time Frank was being slowly forced out of his own company - he would finally depart in 1956, the same year that the company began work on its first turboshaft-powered design, the Vertol Model 107 (first with the Lycoming T53 (first run in 1955) before settling on the General Electric T58, which of course was licenced as the Bristol-Siddeley Gnome in 1958). So Piasecki were pushing the state-of-the-art by offering a Mamba-powered H-21 some three years before they started work on the Model 107. Certainly in 1953 no US turboshaft engine offered sufficient power or was even off the drawing board at that time.

GT6Boy

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 3 November 2017

- Messages

- 53

- Reaction score

- 173

Very interesting indeed- thank you for taking the time to add to thisThanks to a tip from @TsrJoe I pulled a file at Kew on the Piasecki H-21 last week.

The basic outline seems to be: NA.43 had been raised for a tandem-rotor 'single package' ASW helicopter (i.e. one capable of both search and strike with sufficient payload to carry a sonar and a torpedo). An interim order was placed under MDAP funds for Bell HSLs but these never materialised as that helicopter was a flop and cancelled by the USN.

In January 1952 Sir Richard Fairey had travelled to meet Frank Piasecki to discuss a licence for the H-21, talks continuing to June 1953. Fairey pitched the H-21B or C for NA.43 but that was of no interest to the MoA/RN. Therefore Piasecki, via-Fairey, submitted a brochure for the H-21 powered by a single Armstrong Siddeley Mamba 6. Fairey would have been responsible for fitting the US-built fuselages of the first two prototypes with the Mamba and mission systems. Local manufacture would have come later.

Sir Richard Fairey argued that H.21 would not distract his firm from Rotodyne - something the MoA doubted given the resources Westland had to put into Anglicising Sikorsky designs - and would dovetail into the decline of Gannet production. The MoA instead hoped a Fairey-Bristol partnership might be more fruitful. Mr Jones as PDSR(A) went as far to say;

The big stumbling block was that the MoA hated the Mamba as it lacked sufficient power and would offer marginal safety on take-off, it was not a free-turbine and there might be dangerous instability combining the fixed-wheel turbine to the rotor drive (at that time the only successful gas-powered helicopter flown was the Kaman K.225 with the 175hp Boeing YT-50 free-turbine). So the offer was declined.

And at this time Bristol was looking at fitting a developed Bristol Oryx free turbine into the 173 - that would eventually lead to the Gazelle-powered 191 and 192 Series 2.

The lack of suitable British engines again was the problem.

Against that, we should remember that at this time Frank was being slowly forced out of his own company - he would finally depart in 1956, the same year that the company began work on its first turboshaft-powered design, the Vertol Model 107 (first with the Lycoming T53 (first run in 1955) before settling on the General Electric T58, which of course was licenced as the Bristol-Siddeley Gnome in 1958). So Piasecki were pushing the state-of-the-art by offering a Mamba-powered H-21 some three years before they started work on the Model 107. Certainly in 1953 no US turboshaft engine offered sufficient power or was even off the drawing board at that time.

Do you have any electronic copies of the 4 drafts of NA43 or links to the NRO record perhaps?

I repeat my earlier comments regarding your putting this in-print. I'd buy it- I appreciate that might not be sufficient to convince the publishers!

- Joined

- 6 September 2006

- Messages

- 4,340

- Reaction score

- 7,559

I thought I had a copy of Issue IV at least but I think my backup hard drive crash of a few years back wiped that file sadly. The file in question was AVIA 54/865 Anti-Submarine and General Purpose Helicopter (Naval Staff Target N.A.43). I have some written notes on the file but nothing that outlines the actual NA spec.Do you have any electronic copies of the 4 drafts of NA43 or links to the NRO record perhaps?

I have the attached from AVIA 54/916 which outlines the major changes from Issue III to Issue IV. This includes a lot of the deletions to try and save weight (bye bye Pentane etc.).

Somewhere (I hope) I should have a copy of Specification H.R.146D&P that goes with N.A.43.

Attachments

- Joined

- 27 May 2008

- Messages

- 1,047

- Reaction score

- 2,013

Hood: Thank you. GT6: my tone is journalistic, but 2xSycamore dynamics did become 1xT.173 and many Belvederes burnt: “injuries (were) limited (to) sprains incurred by crews vacating (in ) rather a hurry (not) waiting for the ladder.” R.G.Bedford,RAF Rotors,SFB,96,P96.

This reminds me of a retirement speech from years ago, given by a chap who in his early employment, was crew chief working for Bristol Helicopters during the Belvedere development.

Unconnected with the following story, a former RAF Canberra pilot once told me concerning a night time wheels up landing “The crash was easy, over in a flash, didn’t feel a thing…it was being rescued that was the scary and painful bit”. I guess the story below illustrates what he meant.

Avpin, aka Isopropyl nitrate, is a mono propellant liquid that burns by itself in a very energetic manner, releasing a great quantity of gas and heat. It was used as an engine starter system in quite a few U.K. aircraft including the Belvedere. The problems in the early days was find a valve seat seal which would stop the flow when desired, it would leak into the hot exhaust where it would keep burning.

The solution was simple;- a ground based CO 2 fire extinguisher, with a 4m long tube that turns 90 degs at the top (to reach the exhaust on top of fuselage), known as a giraffe extinguisher. Avpin fires were so frequent in the early days and the extinguisher so effective they were just another day, pilots wouldn’t even leave the cockpit.

So our story begins with the Belvedere hot weather service trials combined with a sales campaign to Tehran in about 1961. A flight test Belvedere supported by a Bristol team is on the flight line one morning and the daily flying schedule gets off to a bad start with an Avpin exhaust duct fire, routinely put out, but emptying the extinguisher. They’ve only taken one special giraffe extinguisher so it’s dispatched for refill. The Avpin valve is reworked, and a second attempt at a flight scheduled for after lunch. By the time everyone’s ready for another try the CO2 extinguisher hasn’t been returned so the crew chief pops along to the airfield fire station to ask if they’ll position a fire engine next to the helicopter. They politely decline but offered to be on standby and being only a hundred meters away promise to be at the helo within a minute. One of the firemen would stand outside and if the crew chief give a sign (jumping up and down, waving arms) they would turn out.

And so the second test flight was authorised. Upon engine cranking there’s an Avpin fire, crew chief jumps up/down/waves arms, the chap in the fire station sees him and pulls the crash alarm. The crew chief watches in awe as within a few seconds three fire engines emerge driving in prefect line abreast from the station. All they’ve got to do is left hand turn towards the Helo on the hardstanding. The middle fire engine then turns left but the fire engine to his left doesn’t so there’s a solid crunch as they collide. These two stop, now locked together, the firemen dismount and start yelling at each other. The remaining fire engine avoids the other two, turns and safely arrives at the helo. The firemen get out, grab a ladder and unroll a fire hose, ignoring the crew chief as he shouts “CO2, CO2”.

By chance, a moment later the airfield commander happened to be driving past the scene and pulls up to have a look. He stops his car, gets out, instinctively locks the doors, hears lots of shouting up by the fire station and decides his people skills are far more useful up at the fire station, so trots off in that direction.

Back at the Helo the ladders been set up, firemen with hose is at the top, goes to turn water on and nothing comes out. A panic search finds the car parked on the hose. Meanwhile the crew chief has grabbed a CO2 extinguisher from the fire engine and was slowly climbing the ladder.

In the cockpit, initially it was nothing to worry about, just another Avpin fire, and they were blissfully unaware of the farce unfolding outside. All of sudden the cockpit filled with smoke as the exhaust duct significantly overheated. The Belvedere forward engine was in the fuselage, just behind the pilot so to get from the cockpit to the cargo area was a very narrow but short corridor. This was filled with smoke a dripping molten plastic so the normal exit route was blocked. Hence the pilots pulled back their side doors and jumped. The RAF project pilot landed badly and broke his wrist.

The crew chief was up the ladder, squirting CO2 into the exhaust duct and knocking down the fire (indeed saving the aircraft). it’s a noisy operation but above this he heard a bang. He turned around to see the firemen’s focus had been on moving the car. They’d tied a rope between it and the fire engine and the bang he’d heard was the cars bumper (fender) being ripped off.

Within approx 10 minutes of mayhem they broke;-

One Belvedere

One RAF project pilot

Two fire engines

One Car

And I think one fireman nose

He dryly concluded the hot and high trial was completed albeit late and they for some reason, didn’t get any sales.

I have no idea if this is as it happened, embellished, only repeating as I remember it being told.

Last edited:

Similar threads

-

-

-

-

Escort Cruiser or Light Carrier

- Started by uk 75

- Replies: 41

-

What if Germany went through with VTOL aircraft?

- Started by helmutkohl

- Replies: 53