You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

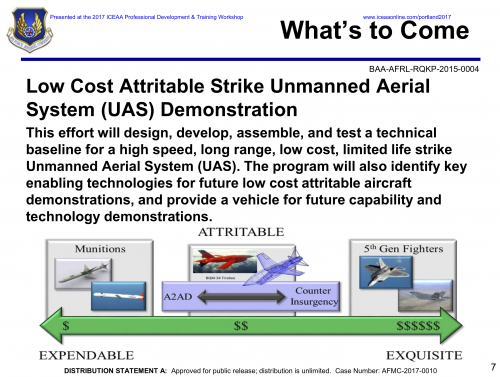

AFRL Low-Cost Attritable Aircraft Technology (LCAAT) Program

- Thread starter Triton

- Start date

- Joined

- 3 June 2011

- Messages

- 17,867

- Reaction score

- 10,892

Sundog said:It has the ability to be rocket launched. I'm trying to find out how it is recovered without a runway. Parachute, net catch, low speed high alpha stall on to a mat?

Any idea how heavy it is?

- Joined

- 16 April 2008

- Messages

- 9,003

- Reaction score

- 12,658

Sundog said:It has the ability to be rocket launched. I'm trying to find out how it is recovered without a runway. Parachute, net catch, low speed high alpha stall on to a mat?

The Valkyrie has a longer range than Boeing’s planned 2,000 nautical miles. It is smaller and rather than using runways, launches like a rocket and lands with a parachute.

I think we should merge this with the existing LCAAT thread, here: https://www.secretprojects.co.uk/forum/index.php?topic=27189.15

- Joined

- 3 June 2011

- Messages

- 17,867

- Reaction score

- 10,892

AeroFranz said:I'm skeptical of rail launch and parachute recovery being conducive to high op-tempo.

And is it launched from a vehicle or fixed ground installations?

- Joined

- 4 May 2008

- Messages

- 2,439

- Reaction score

- 732

Sundog said:More info here. I didn't know it was runway independent. How do they recover it without a runway? Does it carry a parachute to lower itself to the ground or does it fly into a large net that catches it?

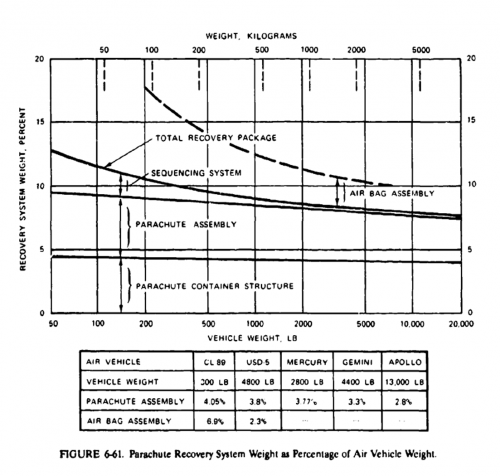

Given the mass and stall speed of this vehicle, it's well outside the prior art of recovery by net. Not saying it can't be done, but that'd have to be one helluva net, is my guess. I'm thinking parachute recovery, with ideally airbags under the fuselage, like Compass Cope and Firefly. Note that something like ten percent of recoveries still end up with significant damage because you can land on uneven terrain, the parachute doesn't separate and you get dragged on the ground, etc. The SDASM flickr archive has some interesting photos of this.

And then there's the fact that once you're on the ground (wherever you ended up drifting), somebody has to pick the vehicle with a crane, drive it back, refurbish it (including parachutes and bags), pick it up and drive it to the launch stand, and attach a rocket booster. that can't be conducive to high sortie generation.

The other thing i don't understand is that all the claptrap required actually exceeds the mass required for a landing gear, which is typically 3-4% (see attached picture). The only advantage i see is being able to claim runway independent operations. But even at the height of the cold war, when arguably the need was stronger, nobody found a way of making that work well. I don't know, i just don't think they thought this through properly.

Attachments

- Joined

- 16 April 2008

- Messages

- 9,003

- Reaction score

- 12,658

sferrin said:AeroFranz said:I'm skeptical of rail launch and parachute recovery being conducive to high op-tempo.

And is it launched from a vehicle or fixed ground installations?

The other Kratos vehicles we've seen are launched from a stand or frame sitting on the ground using a RATO bottle, and I doubt they'e changed the formula a whole lot for XQ-58, except to scale it up as needed. There's no reason you couldn't put a launch stand like that on a pallet that would fit on a trailer or truck bed or on a ship's flight deck. A deployed operational version might want to be containerized for protection, but that's a ways down the road still.

- Joined

- 16 April 2008

- Messages

- 9,003

- Reaction score

- 12,658

AeroFranz said:The only advantage i see is being able to claim runway independent operations. But even at the height of the cold war, when arguably the need was stronger, nobody found a way of making that work well. I don't know, i just don't think they thought this through properly.

I suspect it's just that they are extrapolating from their experience with targets, where parachute recovery has worked well enough. And it avoids developing new software for autonomous landings or adding man-in-the-loop just for landings, either of which would add development cost.

An operational version might well end up doing something different. Boeing clearly thinks wheeled landing gear is better, for instance.

- Joined

- 3 June 2011

- Messages

- 17,867

- Reaction score

- 10,892

TomS said:AeroFranz said:The only advantage i see is being able to claim runway independent operations. But even at the height of the cold war, when arguably the need was stronger, nobody found a way of making that work well. I don't know, i just don't think they thought this through properly.

I suspect it's just that they are extrapolating from their experience with targets, where parachute recovery has worked well enough. And it avoids developing new software for autonomous landings or adding man-in-the-loop just for landings, either of which would add development cost.

An operational version might well end up doing something different. Boeing clearly thinks wheeled landing gear is better, for instance.

Even the LM Minion, that was supposed to be carried in pairs by the F-22, had landing gear.

_Del_

I really should change my personal text... Or not.

- Joined

- 4 January 2012

- Messages

- 1,018

- Reaction score

- 1,218

You could probably even go with an air cushion under carriage that could be useful for a controlled landing or parachute landing.

https://www.secretprojects.co.uk/forum/index.php/topic,6989.0.html

https://www.secretprojects.co.uk/forum/index.php/topic,6989.0.html

marauder2048

"I should really just relax"

- Joined

- 19 November 2013

- Messages

- 3,157

- Reaction score

- 911

Or it's just runway independent for takeoff.

- Joined

- 16 April 2008

- Messages

- 9,003

- Reaction score

- 12,658

marauder2048 said:Or it's just runway independent for takeoff.

There's a quote out there stating that Valkyrie uses parachute recovery. Makes sense to me since it's basically an evolution from Kratos' target drone, which are also parachute recovered.

bring_it_on

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 4 July 2013

- Messages

- 3,231

- Reaction score

- 2,586

marauder2048 said:Or it's just runway independent for takeoff.

Parachute recovery, at least this was what they used for the first flight.

https://aviationweek.com/awindefense/kratos-completes-first-flight-valkyrie-dronehttps://aviationweek.com/awindefense/kratos-completes-first-flight-valkyrie-drone

marauder2048

"I should really just relax"

- Joined

- 19 November 2013

- Messages

- 3,157

- Reaction score

- 911

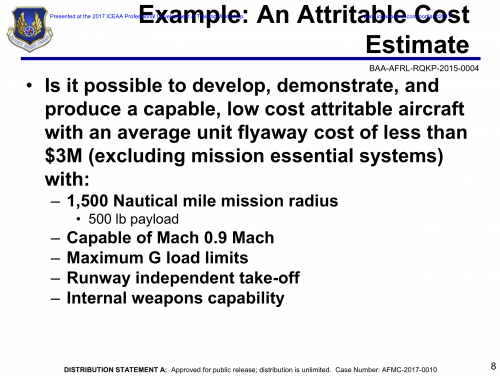

Anyone willing to guess how much mission essential systems would cost?

marauder2048

"I should really just relax"

- Joined

- 19 November 2013

- Messages

- 3,157

- Reaction score

- 911

And here I thought attrition was supposed to be mainly due to enemy action.

The nice thing about "attritable" is that it has no formal definition.

The nice thing about "attritable" is that it has no formal definition.

Colonial-Marine

UAVs are now friend, drones are the real enemy.

- Joined

- 5 October 2009

- Messages

- 1,362

- Reaction score

- 1,110

I like the concept behind this and hope it proves feasible but I have my doubts it will be as cheap as estimated.

I wonder if you could mix a few of these in with a fight of MALDs and send them to serve as a decoy near an S-400 battery with the added bonus of being able to drop some SDBs on the site to further complicate the air defense picture.

I wonder if you could mix a few of these in with a fight of MALDs and send them to serve as a decoy near an S-400 battery with the added bonus of being able to drop some SDBs on the site to further complicate the air defense picture.

red admiral

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 16 September 2006

- Messages

- 1,606

- Reaction score

- 1,849

Triton said:Anyone willing to guess how much mission essential systems would cost?

Indeed

Making a big target drone that looks stealthy doesn't seem that useful. It needs to actually do something other than be a big r/c aeroplane. And that adds a bunch of cost

Dragon029

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 17 March 2009

- Messages

- 881

- Reaction score

- 440

Not necessarily; dropping weapons wouldn't require any mission-essential systems other than ejectors that are relatively inexpensive; the data link systems required to send targeting data should already be integrated for commanding the UCAV itself.

Having the Valkyrie fitted with sensors for ISR or targeting, or EW systems for jamming / decoying, etc, would obviously drive up costs, but at the same time I doubt we're ever going to see particularly expensive gear installed on the Valkyrie; that would probably go to more reusable systems.

Having the Valkyrie fitted with sensors for ISR or targeting, or EW systems for jamming / decoying, etc, would obviously drive up costs, but at the same time I doubt we're ever going to see particularly expensive gear installed on the Valkyrie; that would probably go to more reusable systems.

- Joined

- 21 January 2015

- Messages

- 11,512

- Reaction score

- 14,690

Not sure if this has been posted before on here but this article contains a picture of its wind tunnel model.

https://defense-update.com/20190307_first-flight-of-the-valkyrie-a-step-closer-to-manned-unmanned-flying-formations.html

https://defense-update.com/20190307_first-flight-of-the-valkyrie-a-step-closer-to-manned-unmanned-flying-formations.html

DrRansom

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 15 December 2012

- Messages

- 692

- Reaction score

- 273

The runway independence requirement may also stem from wargames showing serious vulnerability to runways in a precision salvo war. That war game also would encourage much greater numbers to allow for acceptable losses on the ground.

- Joined

- 4 May 2008

- Messages

- 2,439

- Reaction score

- 732

Dragon029 said:Not necessarily; dropping weapons wouldn't require any mission-essential systems other than ejectors that are relatively inexpensive; the data link systems required to send targeting data should already be integrated for commanding the UCAV itself.

Having the Valkyrie fitted with sensors for ISR or targeting, or EW systems for jamming / decoying, etc, would obviously drive up costs, but at the same time I doubt we're ever going to see particularly expensive gear installed on the Valkyrie; that would probably go to more reusable systems.

I don't know where the AirForce stands vis-a-vis of autonomy, but the Army is emphasizing autonomy in its unmanned platforms (like ALE, NGUAS) because of operator workload and the fact that datalinks may or may not be relied upon. So while ideally you could count on the network to pass sensing as well as commands, it's hard to say whether those things will be available.

bring_it_on

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 4 July 2013

- Messages

- 3,231

- Reaction score

- 2,586

AeroFranz said:I don't know where the AirForce stands vis-a-vis of autonomy,

https://www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/capabilities/autonomous-unmanned-systems/unmanned-military-case-study-have-raider-demo.html

bring_it_on

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 4 July 2013

- Messages

- 3,231

- Reaction score

- 2,586

red admiral said:Triton said:Anyone willing to guess how much mission essential systems would cost?

Indeed

Making a big target drone that looks stealthy doesn't seem that useful. It needs to actually do something other than be a big r/c aeroplane. And that adds a bunch of cost

They are chipping away at some of the impediments to low cost attritable UAS companions for 5th and 6th generation aircraft. While this effort is focusing on the vehicle, there are other programs that have been tackling the challenge of fielding more affordable sensor payloads across the radar-EW-and comms space. DARPA's CONCERTO is one such effort that is specifically aimed at the UAS missions and providing affordable multi function capability.

https://www.darpa.mil/program/converged-collaborative-elements-for-rf-task-operations

DrRansom said:The runway independence requirement may also stem from wargames showing serious vulnerability to runways in a precision salvo war. That war game also would encourage much greater numbers to allow for acceptable losses on the ground.

It is primarily a fall out from Ryan heritage and comes as a bonus when dealing with runway availability (drones and Loyal wingmen will be launched en-masse at the same time mission-packages depart from usually crowded runways). You can also extend their range and persistence by forward deploying them.

I found this long-ish twitter thread (8 Mar 2019) by Paul Scharre (Senior Fellow & Director of the Technology and National Security Program at CNAS. Author of "Army of None: Autonomous Weapons and the Future of War.") on the subject highly instructive so instead of rehashing the contents in some inferior form here, I'll just copy it "as is" below.

https://twitter.com/paul_scharre

https://www.paulscharre.com/bio

https://twitter.com/paul_scharre

https://www.paulscharre.com/bio

The newly revealed XQ-58 Valkyrie drone is the future of American air power. Here’s why … [a THREAD]

http://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/26825/air-forces-secretive-xq-58a-valkyrie-experimental-combat-drone-emerges-after-first-flight

The Air Force used to have a lot of planes. A *lot*. As this great @MitchellStudies report shows, the numbers have declined markedly over time.

http://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/a2dd91_5ddbf04fd26e4f72aef6cfd5ee87913f.pdf

The standard narrative is that this is because of budget pressures – from BCA, the wars, etc. There’s some truth to this but it misses the bigger picture, because even in times of budget growth the Air Force inventory has gone down.

From 2001-2008, the Air Force’s base (non-war) budget rose by 22%. The number of combat-coded aircraft *decreased* by nearly 20%.

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/D1KK5EaWsAAwLn0.png

So in lean times, sure, budget pressures have exacerbated these problems, but there are underlying structural issues driving down aircraft inventory even in when the budget is flush. Bottom line: more money won’t solve this problem, only delay it.

What’s killing the Air Force? Rising per-unit cost. This graph is from 2014 and the F-35’s cost has come down since then, but you can see the trend. It’s a harsh exponential curve.

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/D1KLKCdX0AIg0dy.png

(And here’s aircraft per-unit cost over time in a log plot, if you’re into that thing…)

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/D1KLXiUWsAEi3eb.png

Norm Augustine noted this trend in rising per-unit costs back in 1984 as one of Augustine’s Laws. He humorously noted, “In the year 2054, the entire defense budget will purchase just one tactical aircraft. ..."

"... This aircraft will have to be shared by the Air Force and Navy 31⁄2 days each per week except for leap year, when it will be made available to the Marines for the extra day.”

The problem is: (1) it’s three decades later and we haven’t really fixed this problem; and (2) these budget pressures start to be a concern long before you get to one aircraft. They’re a real problem now.

The biggest problem these per-unit costs have had for the Air Force is drive it to an almost-monoculture. The Air Force didn’t just used to be bigger. It used to be more diverse. (Thanks again to @MitchellStudies for this amazing graph!)

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/D1KL6EAWwAIcffV.png

There are cost savings benefits to a more homogenous fleet, to be sure: Fewer programs, so less money spent on R&D. Also lower per unit costs, since you’re buying more a/c at the tail end of production when the marginal cost is lowest. Plus more commonality in maintenance.

But the penalty for a homogenous fleet is enormous. It's a massive operational risk. We’re entering an era where American airpower (which, let’s face it, is the American way of war) will hinge almost entirely on a single program, the F-35. That’s a lot of eggs in one basket.

If there’s a problem with the F-35 (oxygen failure, cyber breach, etc.) that takes an enormous amount of American firepower out of the fight. That’s an unacceptable risk, and the U.S. should never put itself in that kind of position of vulnerability.

But the desire for a multi-mission do-it-all aircraft drove us there.

And the U.S. was sort of forced into that position because aircraft costs have become so eye-poppingly insane that it was the only way to afford 5th Gen aircraft.

Back in the 1960s during the F-100 series the U.S. had *nine* different combat aircraft in operation. Having nine different 5th gen aircraft programs would be totally unaffordable.

Today, however, the Air Force is caught in a death spiral of rising program costs, leading to fewer aircraft, leading to a desire for more efficiency and multi-mission aircraft that can do it all, which further drives up complexity and unit cost.

A diverse fleet is hands down better because it is not only more operationally resilient, but because then aircraft can specialize at missions and be built simpler (and cheaper). But it’s hard to break out of this cycle.

And to make matters worse, adversaries have invested in ballistic missiles that can target U.S. bases, meaning U.S. aircraft will have to operate from further away, which means more time in flight and less time on station. So the U.S. will get less out of the aircraft it has.

This problem of range is a killer. Even if the entire U.S. inventory of F-22s was based in Guam (which is not practical anyway but let’s pretend), it would generate only 6 aircraft over Taiwan to fly 24/7 combat air patrols.

U.S. aircraft are good, but can’t compete with this numerical disadvantage. Rising costs and shrinking numbers, coupled with range, are crippling U.S. airpower and no qualitative advantage 1v1 can make up for this disadvantage in numbers.

To cite just one open-source analysis of this problem, back in 2008 a RAND study of a hypothetical air war with China assumed that U.S. fighters were qualitatively superior (27X better in the case of the F-22), but the U.S. still lost due to China’s superior numbers.

An earlier '08 RAND study assumed that every U.S. missile hit a Chinese aircraft and that every U.S. fighter was invulnerable to Chinese attacks and the U.S. *still* lost the air war because U.S. aircraft ran out of missiles and the Chinese attacked vulnerable AWACS and tankers.

Bottom line: numbers matter.

The Air Force’s response to this has been to take a cue from the Navy and just establish a totally arbitrary number of aircraft and start demanding it. It might be an effective way to argue for a larger budget, but it won’t save the future of American airpower.

You can add more money, but if you don't change the paradigm, Augustine’s Law will just keep eating those dollars. You can’t buy your way out of this exponential death spiral of rising costs, just delay the inevitable.

Enter the Valkyrie. There’s not that much to it. It’s not going to go toe-to-toe with an F-22. It’s not even comparable. It’s basically a larger, modular, recoverable cruise missile. But it’s designed to be cheap and attritable. And that’s the genius of it.

It’s not just that you can buy a lot of Valkyries cheaply. You can, but 100 of them still won’t substitute for an F-35. But that’s not the point. They’re not supposed to. What they are supposed to do is augment the combat capability of F-22s & F-35s inexpensively.

Don’t envision what the Valkyrie can do on its own. The real question is what an F-35 could do with 8 or 16 of these helping it. And the answer is these will make existing F-22s and F-35s far more capable at their job. This is the machine in human-machine teaming.

Cheap attritable UCAVs like the Valkyrie can bring #s and diversity back to U.S. airpower. The USAF can buy a whole lot of these – 1000s of them – cheaply and equip them with a diverse set of sensors and payloads for a range of missions: strike, ISR, EW, decoys, jamming, etc.

Best of all, they allow the USAF to upgrade combat power cheaply & quickly by changing how we think about modularity. Right now, systems can be upgraded by making them modular: Payloads over platforms, software over payloads. But a drone like the Valkyrie expands that further.

Now, the combat system is no longer the platform. It’s beyond that. It’s a team of platforms working together. So if you want to upgrade the combat system, you’re not constrained by the SWAP (size, weight, and power) of the platform. You just plug a new platform into the team.

This was the thought behind the DARPA SoSITE program, which aimed to move from a platform-centric model of combat power to one that relied on distributed functionality among a diverse mix of heterogenous, low cost platforms.

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/D1KOfSNWwAIpQDR.png

This distributed system concept has a number of advantages. It’s harder for the enemy to target, presents them with more numerous and diverse challenges, is more resilient to disruption (less brittle), and it’s easier to upgrade faster and at lower cost.

The U.S. has been constrained in adopting this approach to date because it requires accepting some air vehicles aren’t going to be fully capable multi-mission aircraft. They might be special purpose vehicles and might be attritable, meaning it’s acceptable to lose them.

It’s possible to adopt this model with people, but it requires treating your people more expendably that the U.S. military does today. And it also doesn’t make sense with an all volunteer force where the number of pilots is limited.

Low-cost attritable aircraft make a lot of sense when drones are involved, though, and can be a real game-changer for the Air Force.

Not all drones will be cheap and expendable. There is a role for expensive, exquisite systems as well. But attritable drones fill an important niche in the aircraft ecosystem.

Most importantly, they are essential for bringing back numbers and diversity, which are important for helping secure another generation of American air power.

An Air Force with thousands of Valkyrie-like drones augmenting its F-22s, F-35s, and B-21s will be far more capable than one without. The real question will be whether Air Force leadership will make those investments a priority and bring this future into reality.

For more on what robotic swarms can do, check out this @CNASdc report:

https://s3.amazonaws.com/files.cnas.org/documents/CNAS_TheComingSwarm_Scharre.pdf

- Joined

- 6 September 2006

- Messages

- 4,582

- Reaction score

- 8,514

The same problem will eventually apply to China as well.

About 44% of their fighter fleet of 1,085 are MiG-21 knock-offs of doubtful capability. Even if they keep churning out Flanker copies and J-20s and later 6th gen types, the costs are unlikely to enable a 1-1 replacement of older airframes, although any fleet renewal will increase the overall effectiveness of their force as the older J-7s and J-8s retire. Of course when China builds 1,000 similar LCAATs during the 2020/30s the balance would be restored.

About 44% of their fighter fleet of 1,085 are MiG-21 knock-offs of doubtful capability. Even if they keep churning out Flanker copies and J-20s and later 6th gen types, the costs are unlikely to enable a 1-1 replacement of older airframes, although any fleet renewal will increase the overall effectiveness of their force as the older J-7s and J-8s retire. Of course when China builds 1,000 similar LCAATs during the 2020/30s the balance would be restored.

bring_it_on

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 4 July 2013

- Messages

- 3,231

- Reaction score

- 2,586

Has the USAF articulated what will happen to the program once it completes its 5 flights?

- Joined

- 3 June 2011

- Messages

- 17,867

- Reaction score

- 10,892

bring_it_on said:Has the USAF articulated what will happen to the program once it completes its 5 flights?

If the past is any indicator it will probably whither away on the vine.

marauder2048

"I should really just relax"

- Joined

- 19 November 2013

- Messages

- 3,157

- Reaction score

- 911

AeroFranz said:Dragon029 said:Not necessarily; dropping weapons wouldn't require any mission-essential systems other than ejectors that are relatively inexpensive; the data link systems required to send targeting data should already be integrated for commanding the UCAV itself.

Having the Valkyrie fitted with sensors for ISR or targeting, or EW systems for jamming / decoying, etc, would obviously drive up costs, but at the same time I doubt we're ever going to see particularly expensive gear installed on the Valkyrie; that would probably go to more reusable systems.

I don't know where the AirForce stands vis-a-vis of autonomy, but the Army is emphasizing autonomy in its unmanned platforms (like ALE, NGUAS) because of operator workload and the fact that datalinks may or may not be relied upon. So while ideally you could count on the network to pass sensing as well as commands, it's hard to say whether those things will be available.

Probably depends on what form of Auto-ICAS (an absolute requirement for Loyal Wingman) is adopted.

The datalinks and sensors there have to be very robust.

- Joined

- 21 January 2015

- Messages

- 11,512

- Reaction score

- 14,690

Now completed its second flight.

Janes | Latest defence and security news

Janes | The latest defence and security news from Janes - the trusted source for defence intelligence

www.janes.com

Last edited by a moderator:

- Joined

- 9 October 2009

- Messages

- 21,084

- Reaction score

- 12,137

Air cushion landing system of some sort, perhaps?

- Joined

- 16 April 2008

- Messages

- 9,003

- Reaction score

- 12,658

Air cushion landing system of some sort, perhaps?

Parachute.

- Joined

- 9 October 2009

- Messages

- 21,084

- Reaction score

- 12,137

I meant the eventual production version, but thanks anyway.

- Joined

- 21 January 2015

- Messages

- 11,512

- Reaction score

- 14,690

US Air Force looks to fast track cash to Kratos Defense for more Valkyrie drones

The Air Force is taking a growing interest in "Loyal Wingman"-type unmanned systems that are cheap enough to be discarded when shot down.

TAOG

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 7 October 2018

- Messages

- 102

- Reaction score

- 208

XQ-58A can carry four SDBs internally.

www.military.com

www.military.com

Air Force's Future Stealthy Combat Drone Could Use AI to Learn

Kratos Defense completed its second test flight of the XQ-58A Valkyrie unmanned aerial vehicle on June 11 in Yuma, Arizona.

- Joined

- 21 January 2015

- Messages

- 11,512

- Reaction score

- 14,690

Janes | Latest defence and security news

Janes | The latest defence and security news from Janes - the trusted source for defence intelligence

www.janes.com

Similar threads

-

-

U.S. Transportation Secretary Announces Unmanned Aircraft Registration

- Started by Dragon029

- Replies: 9

-

-

-

USAF to Retire B-1, B-2 in Early 2030s as B-21 Comes On-Line

- Started by flateric

- Replies: 319