Since 1916, a new fabric began to be used by the Central Powers in the Western Front, that patterned with polygons of different colours reduced the visibility of airplanes confusing them with the ground tones.

The new camouflage system was named ‘Lozenge-Tarnung’ and based its design on the Impressionists painters that, it was discovered, had a distortional optical effect during combat manoeuvres that made the enemy accurate aim very difficult.

By the end of the ninetieth century, zoologists discovered that the tiger stripes mimic the vertical shadows in the reed beds where they hide for hunting. On the other side, the zebras stripes seem designed to increase visibility; however, five out of six lion attacks fail, due to more subtle causes. As it turns out, due to the movement of the animal, the rhythmic waving caused by the black stripes produces an optical distortion (known as ‘akinetopsia’) that affects the way in which the brain calculates distances.

The Royal Navy was the first to apply this principle to the naval war but, towards 1915, almost every warship was painted with white, black, grey and blue diagonal stripes to disorient the telemeters of the enemy artillery.

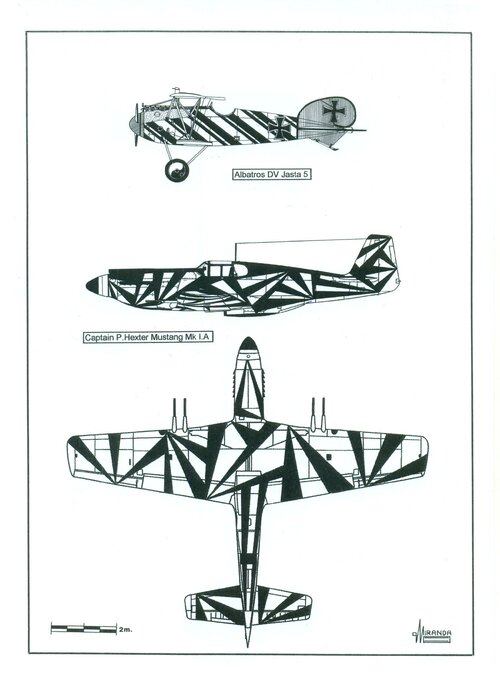

In the air, the fighters Albatros D.V of the Jasta 37 were the first to use the optical distortion techniques, with its tailplane painted in black and white diagonal stripes. In combat, the violent turns of the airplane achieved the ‘zebra effect’ thus disrupting the aiming of the British pilots. They had the additional resource to use the Iron Crosses painted on the upper wing as reference, but the Lozengue camouflage and the aircraft vibration during tight turns made the distance estimation very difficult in deflection shooting. The Fokker DR.I of the Jasta 6 also used the ‘zebra effect’ painting the tailplane, the fuselage and even the interplane struts with stripes.

The system worked and towards 1917 almost every German reconnaissance two-seater airplane, operating in the Western Front, had a rectangular patch of diagonal stripes on their fuselage.

The British airplanes started to imitate them. In 1918 it was common to see the F-2B and ‘Camels’ of the RFC with series of white bands painted over the khaki of the rear fuselage.

The technique reached its peak of refinement during the summer of 1918 with the Albatros DV flown by Ltn. Fritz Rumey, assigned to the Jasta 5, an elite squadron. In this airplane, the diagonal stripes had four different widths and had been painted in spiral (like on a candy) along the fuselage.

The Austrians had their own mind about the subject. They started painting small spirals on the upper surfaces of the Phönix fighters but, around 1917 they camouflaged the Aviatik with a special scheme of hexagons which colours varied in intensity, lighter on the wing tips and tail surfaces, to blur the characteristic shape of the airplane.

The British had a problem with the colour of their airplanes. Since 1915 all were brown and both the fighters and the anti-aircraft artillery had the tendency to open fire against anything painted in another colour….. French ones included. As a consequence, their experiments were more conservative, although at the end of the war some airplanes carried the roundels of the upper plane painted in asymmetric position to confuse the enemy, as it happens with the false eye that some tropical fishes had near the tail. They also used additional, more blurred roundels, painted on unusual spots of the airplane, like the tailplane, the back of the fuselage or the central section of the upper wing.

In 1918 limited essays were made on skewed-perspective box-grids, diminishing overlapping rectangles and high visibility but misleading geometrical designs. These experiments were shaped by advice from painters of the ‘Vorticist School’ (Britain’s version of Futurism) like Wyndham Lewis and their ultimate objective was to create in the enemy pilot that second of doubt and confusion that frequently is key to escape.

The end of the WWI did not end with these practices. In 1923 the Finnish Fokker D.VII were painted on a ‘splinter’ scheme in dark blue, light grey, purple and light green. During the 30s, the new Luftwaffe started to use the ‘splinter’ in two or three different shades, although some Heinkel 45, seen during the Spanish Civil War, still kept the ‘Lozenge’ camouflage.

In 1935 the Hawker Demon fighters of the 74 sqn of the RAF, based in Malta, tried a new type of camouflage based on ochre, yellow, grey, green and brick red, with just one roundel on upper wing starboard and the opposite side aileron painted in aluminium!

The general idea, apparently not very successful, was not to make the plane hard to see but hard to be shot at by enemy pilots.

The Munich crisis of September 1938 served, among other things, to prove how unprepared were the French and British air forces for the war. At that time, London was defended by biplanes that were slower than a ‘postal’ Heinkel He 111. The Hawker Fury and the Dewoitine 510 lost their aluminized painting of peace time that was hastily covered with a dark green layer.

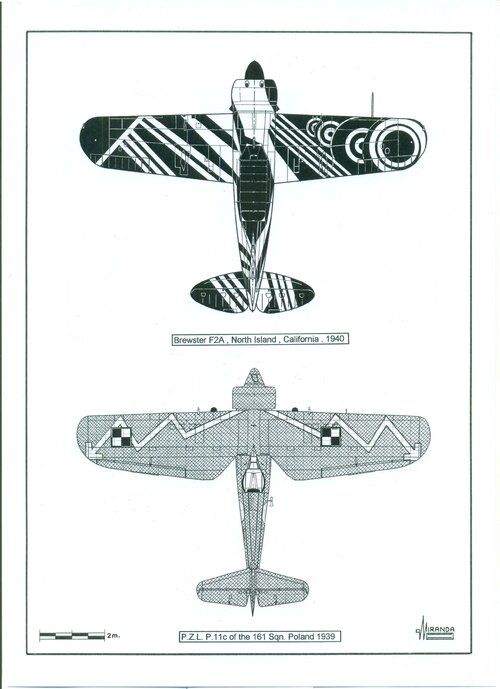

Despite their theoretical neutrality, the North American airplanes also lost the chrome yellow on their wings. In 1940 the US Army Air Corps performed low visibility camouflage tests with some Curtiss P.36 and Northrop A-17 A. The US Navy repeated the British experiments of the ‘Vorticist School’ with some Brewster F2A and Northrop BT-1 in North Island, California. Finally mass production prevailed: Seversky and Curtiss in olive drab, Brewster and Grumman in naval grey.

In 1939 the colour of the European aviation was as dark as its future. The Germans used splinter in two shades of dark green. The British used dark green, dark earth and black and white undersides. The French used earth, ash and dark green. Over the French-German border all the airplanes looked the same. The Bf 109 shot down Belgian Hurricanes on neutrality patrols, mistaking them for British fighters. The authentic Hurricanes of the BEF shot down Potez 630 confusing them with the Bf 110 and were attacked by Morane fighters that took them for German airplanes.

Only the Poles showed some creativity. When entering the war with Germany most of their fighters were well positioned in auxiliary aerodromes, the square shaped national markings were painted on the wings in asymmetric position and some P.Z.L. P.11C fighters of the 161 squadron had schemes of optical distortion painted in zig zag over the wings, although that was not nearly enough to overcome the technical and numeric superiority of the Luftwaffe.

During the World War II, when airplanes were manufactured by tens of thousands, the dynamic of the assembly lines did not allow any experiment with complex camouflages. There was not even the time to paint the airplanes and many Mustangs, Forteresses and Thunderbolts were delivered with the naked aluminium coating, while nationality roundels were replaced by big decals to save time and hand work!

In the battlefield that covered from the jungle to the sea and from the Arctic to the desert, things were very different and the airplanes received any type of conceivable camouflage to get unnoticed against the ground they flew over. Some missions, like the stratospheric combat, photographic reconnaissance or night fighting, required specially modified airplanes with camouflage schemes adapted to the environment on which they should operate.

The Ju 86P, Bf 109 G-6/AS, Spitfire HF Mk VIII, Westland Welkin and D.H. Mosquito NF.XV, intended for high altitude combat, used to go wholly painted light grey. The Lockheed P-38 F-5 that photographed the Ruhr at medium height, were painted bluish fog-grey; the Spitfire P.R.Mk IV and Mosquito P.R. Mk XVI were painted a deep blue colour, to rest them visibility against the sky colour at high altitude, while the Spitfire P.R. Mk VII of the541 Sqn, operating at dawn with clear weather, were painted in pink colour. For the darkness war, the RAF painted in black the under surfaces of all its bombers, to make them less visible to the reflectors.

Until 1943, all night fighters were painted in black. Germany used the Arado Ar 68E, Bf 109 E-4, Bf 110 C-6 and E-2, Do 17 Z-10, Do 215 B-5 and Do 217 J and N. The British used the Defiant Mk II, Hurricane Mk II, Beaufighter Mk II, Mosquito NF.Mk II, and even some Spitfire Mk VB of the 111 Sqn. At the beginning they used an extra matt anti reflective paint, but it turned out that it produced drag, limiting the airplanes speed.

The Americans operated in Europe and in the Pacific with Northrop P-61 and Douglas Havoc II, the Japanese used the Nakajima J1N1-S Gekko, the Italians, the Caproni Vizzola F-5 and the French the Potez 631. It seemed to be the most logical solution, but the black painting did not work out well. The airplanes were very visible from above, when flying over clouds lighted by the reflectors.

The Germans started to use this advantage in August 1943, using conventional fighters Bf 109 and Fw 190 in the ‘Wilde Sau’ night operations. In the winter of 1942, some Do 215 B-5 and Do 217 J night fighters were experimentally painted in light grey, to make them less visible to the gunners of the Lancaster and to the pilots of the Mosquito NF. II of escort. The results were good and it was ordered that all night fighters and ‘Wilde Sau’ would be fully painted with RLM 76 ‘Hellblau’ (light blue).

Recalling the experiments made with the ‘night’ Lozenge for the Gotha bombers, in the WWI, the hazy effect was improved making the shape of the airplanes blurred by means of patches or ‘worm’ schemes of RLM 75 ‘Hell Violett-Grau’ (light grey violet). I worked better with the big airplanes Ju 88 G-6, Do 217 N and Bf 110 G-4 while the fighters Bf 109 G-5 / G-6 and the Fw 190 A-6 were light grey RLM 02 ‘Grüngrau’. Some had the underside starboard wing painted in black for identification of the flak.

Since 1943, the night fighters Mosquito adopted the idea, changing the overall black by the standard daylight camouflage in dark green and ocean grey upper surfaces, keeping the under surfaces in the previous black colour, that the RAF considered useful against reflectors, provided that they flew over the layer of clouds.

The accurateness and volume of fire of the flak increased daily. From the viewpoint of the British fighters that made straffing missions over the occupied France, the number of casualties grew until 1945… the Reich vomited flak.

In 1942, Captain Paul Hexter designed a black and white dazzle camouflage scheme for the underside of the attack airplanes. It was tested in a Mustang Mk IA proving that, like the warships of the WWI, it distorted the distance calculation of German telemeters during flights at low altitude, by the so known ‘zebra effect’. Its use was never generalized due to its difficult maintenance. In the Mediterranean the Savoia 79 of the Regia Aeronautica were too visible over the sea, with their ‘Sicilian’ camouflage. Some machines specialised in attacks with torpedoes received a layer of light grey painting in the front of the fuselage and wings leading edges to diminish its frontal visibility.

In the Atlantic, antisubmarine aircrafts of the US Navy had the same problem: the U-Boat immersed at the lowest sign of sighting. In 1943, an experiment was performed under the Yehudi code-name to diminish the frontal visibility against the luminous background of the sky. It consisted of 10 sealed-beam lights, installed along the wings leading edges and the rim of the engine cowling of an Avenger TBM-3D bomber. The tests proved that the Yehudi system lowered the visual acquisition range from twelve to two miles.

The entry into service of the new centimetric radars, that the ‘Metox’ detectors of the Kriegsmarine could not detect, disrupted the balance in the Battle of the Atlantic, rendering the Yehudi useless. But the experiments went on using a Liberator and were only declassified in the 80s.

During the Vietnam war, the idea was resumed under the ‘Compass-Ghost’ code name and the tests made with a blue and white F-4 Phantom, lighted by nine high-intensity lamps on the wings and fuselage, reduced the detection range a 30 percent.